Effects of Poultry Farm Waste on the Survival and Growth of Rohu (Labeo rohita)

| Received 20 Mar, 2025 |

Accepted 23 Nov, 2025 |

Published 31 Dec, 2025 |

Background and Objective: The poultry farm waste is considered to be a protein and energy source and thus can be used to establish the polyculture of poultry and fish. So, the study aimed to evaluate the potential of poultry farm waste (PW) as a dietary component for rohu (Labeo rohita) by assessing growth performance, Weight Conversion Coefficient (WCC), and Feed Conversion Ratio (FCR) over a two-month feeding trial. Materials and Methods: The PW was collected from the Government Poultry Farm, Peshawar. Dried and analyzed for its nutritional composition at the Poultry Section of the Veterinary Research Institute (VRI), Peshawar. Then used this as the sole feed twice a day for months and observed the growth performance of fish by WCC. All data were analyzed using one-way ANOVA (p<0.05) in SPSS to evaluate the impact of poultry farm waste on the growth performance of rohu (Labeo rohita). Results: The proximate analysis of PW revealed it contained 95.08% dry matter, 46.06% ash, 25.5% fiber, 14.06% crude protein, 1.92% fat, and 48.36% carbohydrates. During the feeding trials, WCC initially exhibited lower values but improved significantly by the conclusion of the experiment. Conclusion: The findings indicate that PW, when utilized as a sole feed, is a viable and cost-effective option for enhancing fish production. The study provides a foundation for further exploration of PW as an alternative feed source in aquaculture.

| Copyright © 2025 Ullah et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. |

INTRODUCTION

In developing countries, the rapid increase in the volume of solid waste has emerged as a critical environmental challenge1. This issue is compounded by inadequate management of municipal solid waste, liquid waste, air, and noise pollution, as well as the provision of safe drinking water. Among the contributors to this environmental problem are poultry farms located within urban areas, which generate substantial quantities of manure. Poultry manure, rich in nitrogen and phosphorus, is a significant source of environmental pollution, contributing to water eutrophication, air contamination, and soil degradation2.

Despite its environmental implications, poultry waste (PW) holds considerable nutritional value, particularly due to its high crude protein (CP) content, which surpasses that of waste from other animals with lower CP concentrations. This nutrient-rich byproduct can be repurposed for use in animal feeds3. Poultry litter a composite of excreta, residual feed, feathers, and bedding materials such as wood shavings, sawdust, peanut hulls, straw, and other dry absorbent materials has traditionally been utilized in agriculture as a highly valued organic fertilizer4.

The scale of poultry waste generation is substantial, with poultry layers producing approximately 95.2 g/day (666.4 g/week, 2856 g/month) and poultry broilers generating about 63.5 g/day (444.5 g/week, 1905 g/month) of manure5. This waste, particularly poultry litter, can be recycled and incorporated as a partial substitute for conventional, costly grains and oilseeds in livestock nutrition.

In aquaculture, nutrition plays a pivotal role, as feed accounts for 40-50% of production costs. Significant advancements in fish nutrition have led to the development of balanced commercial diets that enhance growth and health, tailored to specific species. These diets support the expansion of aquaculture to meet the growing demand for affordable, high-quality fish and seafood6. While poultry waste and other animal byproducts are commonly used as fertilizers to promote natural food production in aquaculture, their direct use as feed for fish remains underexplored. Dried poultry excreta have long been recognized as an excellent source of protein and minerals for ruminants. However, limited research exists on its application as a feed ingredient for fish diets7-10.

Given this gap, the present study was conducted to evaluate the effects of incorporating dried poultry excreta as a sole feed ingredient on the growth performance of rohu (Labeo rohita). This research aims to provide insights into the potential of PW as an alternative, cost-effective feed source in aquaculture.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study area: The study was carried out in April, 2023, in the Fisheries Laboratory, the Department of Zoology, the University of Peshawar, for a one-month period.

Sample collection: Samples of poultry farm waste were collected from a government poultry farm in Peshawar. The collection was carried out through a spade and Tin; 3 kg of poultry samples were collected. Then, PW were weighed through a digital balance (ML204, Mettler Toledo (Switzerland)). The 1 kg of poultry waste was separated and kept in an incubator (IF110, Memmert (Germany)) at a temperature 60oC for 72 hrs. At regular observation after 72 hrs, the poultry wastes were dried and kept in the sun for 1 to 2 hrs that the remaining moisture was evaporated. After drying, the weight of the sample decreases to 0.75 kg. When the total samples were dried, their weight was reduced to 2.25 kg.

The next collection was carried out on 3rd April 2013, also from a government poultry farm in Peshawar.

Grinding of poultry sample: The poultry samples were ground through a grinder (Thomas-Wiley Laboratory Mill Model 4, Thomas Scientific USA). A 1 mm mesh size was used in the grinder during grinding. The process of grinding was carried out in the Animal Nutrition Department, the Agriculture University, Peshawar.

Chemical analysis of poultry farm waste (P.W): Chemical analysis of poultry farm waste (P.W) was done in the Veterinary Research Institute (VRI), Peshawar. Poultry farm waste (P.W) consisted of dry matter, protein, carbohydrate, fats, and ash. The chemical analyses of poultry farm wastes were performed through the following methods8.

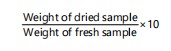

Determination of dry matter in poultry waste: The 2 g of poultry wastes sample was taken and weighed in a pre-weighed crucible. The crucible was placed in hot air oven at 100oC overnight (samples may also be dried at 135oC for 2 hrs). The crucible was taken out; cooled it in a desiccator and weighed:

Calculation:

|

Determination of ash in poultry waste: The dried crucible containing dry matter was placed in a Muffle furnace at 550°C for 5 hrs. The crucibles were cooled in desiccators and weighed.

Calculation:

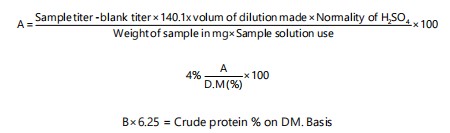

Determination of crude protein in poultry waste: The 0.5 g sample were weighed and then put it in Kjeldahl flask and 2 spoons (2-3 g) of digestion mixture in it. The 10 mL of H2SO4 added in it. Boiled it for 30 min until the color changed to green. The digestive samples were cooled. Added distilled water. And made it 100 mL in a volumetric flask. The 25 mL sample (in duplicate) was taken in a distillation flask. The 50 mL distilled water was added to it. The 15-20 mL NaOH solutions (40%) were added and placed in a heater. Then, 10 mL of boric acid reagent was placed in the receiving flask. The color of the boric acid reagent was changed during distillation. Titrated it against 0.02N H2SO4 solution and noted the titration reading.

Calculation:

|

The 0.2 g of acetanilide was weighed, digested, distilled & titrated, calculate nitrogen. Acetanilide contains 10.36% nitrogen. The control value tells the efficiency of the whole system, and this shows accuracy. A control is needed for each series of analysis. Distilled 5 mL of (NH4)2SO4 recovery solution. Titrated it against 0.02N H2SO4 solution & note the titration reading.

Calculation:

If titration reading is 3.9 and blank volume is 0.35, then (3.9-0.35)×14.01×0.02×10 = 99.47.

Determination of crude fiber in poultry wastes: The 2 g of samples were weighed and poured into a tall beaker. The 100 mL of (0.15M) H2SO4 was added to it. Some glass beads were added to facilitate quick boiling and then heated for 5 min. The heat supply was adjusted. Reflux exactly for 30 min. The 50 mL of 1.5 M NaOH solution was quickly added and boiled for 35 min. The hot solution was filtered over the crucible and the beaker with hot water. The filtrate was washed with 50 mL of 3M HCL solution. Again, it was washed with hot distilled water until free of acid. Rinse with 10mL acetone. Dried the crucibles with contents in the oven at 135°C for 2 hrs. Allowed to cool in desiccators and weighed. The crucible was placed in the Muffle Furnace for 2 hrs at 550°C. Allowed to cool in desiccators and weighed.

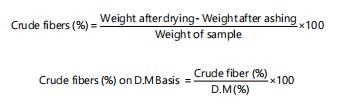

Calculations:

|

Determination of crude fat in poultry waste: The 2 g samples were weighed on a filter paper. Then the filter paper was placed along with the sample in the extraction thimble. The thimble was placed in a Soxhlet extractor fitted with a condenser. Poured 150-200 mL of ether is in the pre-weighted empty flask. The flask was attached to the extraction apparatus over a hot plate. On heating the flask ether was evaporated, condensed, and fell in the form of drops on the sample. The condenser was filled with ether, and the fat from the sample will automatically back into the flask. The process was repeated for 5 hrs. At the end of the extraction, remove the thimble from the apparatus. Distil the ether and then pour it into a bottle. The ether evaporated was left in the flask by drying in an oven at 70-80°C for 2 hrs. Cooled the flask in desiccators and weighed.

Calculations:

|

Granules formation: The poultry farm wastes (P.W) were passed through a 1.5 mm mesh size, because of low stickiness and low availability of protein, added an 11.5% solution of gelatin. This way the waste becomes moist and then dried it in the incubator until 5% moisture remained. After incubation, the wastes were passed through a 1.5 to 2 mm mesh size, and granules were formed.

The size of the granules was calculated.

Fish culture: Three aquaria were taken, and 13 fingerlings were in each treatment. One aquarium was taken as a control group, and 12 fingerlings. Then weighed each aquarium fingerling and also control fingerlings through an electronic balance type EB_430D. The temperature of all aquaria and the temperature of Peshawar were recorded. The experiment was carried out in the Fisheries Laboratory, Department of Zoology, University of Peshawar. A thermometer (Hanna HI145-00 (digital, 50 to 150°C, ±0.3°C accuracy) was fixed in all aquaria to find the temperature. The feed was given to the fish according to their body weight. The aquarium was labeled as A, B & C.

Feeding ratio: First, all the fishes given 2% of their body weight in feed, then it increases to 2.5, 3 and 3.5%. Due to off off-season, the remaining experiment was performed on 2% of body weight feed.

Food conversion ratio: The FCR of feeding trial experiment can be calculated according to the formula:

Growth performance: The weight conversion coefficient (WCC) was calculated through the following formula:

WCC = Total Weight gain by fish×10 |

Statistical analysis: All data were statistically analyzed using SPSS software. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) where the p-value is less than 0.05 (p<0.05) was employed to assess the impacts of poultry farm waste on the growth performance of rahu (Labio rohita).

RESULTS

Chemical analysis: The proximate composition of poultry waste (PW) as indicated in Table 1 highlights its potential as a nutrient source in aquaculture. With a high dry matter content (98.08%), PW offers concentrated nutrients and stability for storage. Its substantial ash content (46.06%) indicates a rich mineral profile essential for fish growth and metabolic functions, though careful inclusion is required to avoid imbalances. The moderate crude protein level (14.06%) provides an economical alternative to conventional protein sources, while the high carbohydrate content (48.36%) offers an affordable energy source, reducing dependency on protein for energy metabolism. However, the high fiber content (25.5%) could limit digestibility, and the low-fat content (1.92%) may necessitate supplementation with other lipid sources. These results suggest that while PW can serve as a cost-effective feed ingredient, its high ash and fiber levels must be managed, and further optimization is needed to maximize its utility in aquaculture diets.

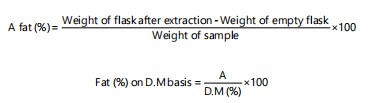

Growth performance: The weight conversion coefficient (WCC) was calculated through the above formula, and the result is indicated in Fig.1. In Experimental A, weight gain and loss fluctuated, with readings showing both positive and negative trends, indicating variable outcomes in this group. Experimental B exhibited predominantly weight loss across all readings, with a significant decline in some instances, suggesting that the conditions in this group were not conducive to weight maintenance or gain. Experimental C showed the most drastic weight loss, particularly in one reading, highlighting potentially adverse conditions in this experimental setup. In contrast, the Control group consistently demonstrated weight gain or stability across all readings, reflecting optimal or normal conditions for growth.

The results suggest that the experimental conditions, particularly in groups B and C, may have been less favorable for weight maintenance or growth, likely due to diet, environmental factors, or other variables. The consistency in the Control group supports the hypothesis that standard conditions promote growth. These findings emphasize the need to refine experimental parameters to mitigate adverse effects in experimental groups.

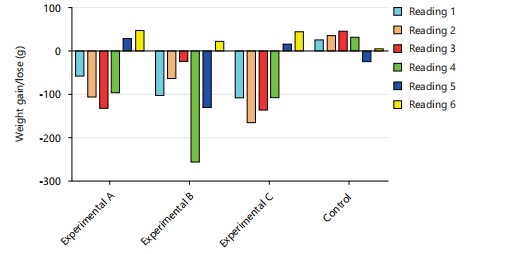

Survivability/mortality record: Figure 2 illustrates the mortality rates recorded across six readings in three experimental groups (Exp A, Exp B, and Exp C) as well as the Total category. In Experimental A, mortality remained relatively low during most readings, with a notable spike in reading 3 (8 mortalities). Experimental B also exhibited low mortality rates across readings, but a significant increase occurred in reading 3 (5 mortalities). Experimental C, however, displayed the highest mortality rate, with a substantial peak in reading 3 (9 mortalities), indicating more adverse conditions compared to the other groups. The Total category shows no mortality recorded, suggesting it aggregates data under optimal conditions or a control scenario.

The overall trend highlights reading 3 as a critical point across all experimental groups, showing significantly higher mortality rates. This may suggest unfavorable environmental conditions, feed quality, or other stressors during that period. In contrast, the absence of mortality in the Total category indicates stable and ideal conditions. These results emphasize the need to investigate the factors contributing to the higher mortality in Experimental groups, particularly during reading 3.

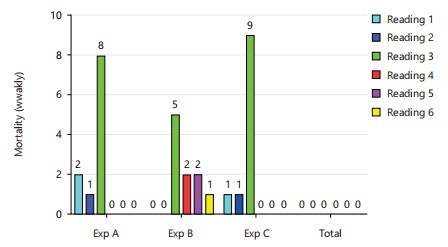

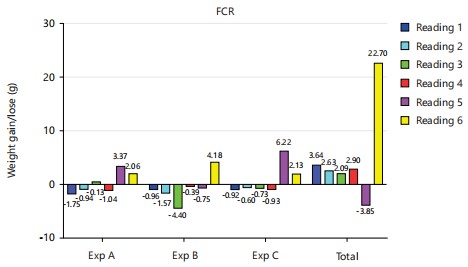

Food conversion ratio: The FCR is a measure of feed efficiency, where a lower FCR indicates better feed utilization for weight gain. Experimental A shows relatively consistent FCR values with moderate variations across readings as indicated in Fig. 3. However, some readings indicate negative weight gain (loss), leading to an unfavorable FCR. This suggests suboptimal feed utilization in this group. Experimental B displays similar trends, with slightly more pronounced negative values for FCR in certain readings, indicating poorer feed efficiency and weight loss in specific periods. Experimental C shows the most significant variations, with a mix of low positive and highly negative FCR values. This group exhibited the poorest feed utilization overall, highlighting potential issues with the diet or environmental conditions. The Control Group achieved the best feed efficiency, with a consistently positive FCR. Notably, reading 6 stands out with a significantly high FCR value (22.77), indicating exceptional weight gain during this period and optimal feed utilization compared to the experimental groups.

|

|

|

| Table 1: | Chemical analysis of poultry farm waste | |||

| Dry matter | Ash | Fiber | Crude protein | Fats | Carbohydrate | |

| ( P.W) % | 98.08% | 46.06% | 25.50% | 14.06% | 1.92% | 48.36% |

Overall, the Fig. 1-3 highlight that the control group performed better in terms of feed efficiency, while all experimental groups faced challenges with feed utilization, particularly Exp C. The results suggest that the diets or conditions in the experimental setups may require adjustments to improve FCR and overall fish performance.

DISCUSSION

Poultry waste (PW) has been studied extensively as a potential component of animal diets, yielding varying results depending on its application. Typically, PW has been utilized as a supplementary feed. For instance, Ayoola11 conducted a 12-week feeding trial using poultry hatchery waste as a supplementary diet for Clarias gariepinus. The study observed a slight reduction in haematological parameters, including Packed Cell Volume, Haemoglobin, and Red Blood Cell counts, compared to fish fed the control diet. Despite these changes, Ayoola concluded that the health status of the fish was not adversely affected. Similarly, Nyina et al.12 evaluated soybean and dried poultry waste-based concentrates as supplements to Cynodon nlemfuensis in West African Dwarf goats. Their findings revealed that soybean-based diets achieved the highest feed conversion efficiency compared to diets containing dried poultry waste. Zheng et al.13 investigated replacing soybean meal (SBM) with cottonseed meal (CSM) in the diet of grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idella) and found that a diet containing 16.64% CSM, replacing 35% of SBM, did not significantly affect weight gain, feed efficiency ratio, or feed conversion ratio.

In the present study, poultry farm waste was explored in a novel approach as the sole feed for rohu (Labeo rohita) fingerlings. The fingerlings were fed at 2% of their body weight throughout the experiment. Initially, negative growth was observed in all experimental groups, particularly during the first 40 days. However, after the fourth reading, some fish began exhibiting positive growth, and by the end of the trial, all experimental groups showed consistent weight gain. The initial negative growth may be attributed to the fish's acclimatization period, as the poultry waste feed differed significantly in texture, taste, and nutritional composition from conventional hatchery feeds. The low protein and fat content of the PW likely hindered tissue formation, while the absence of a vitamin premix further exacerbated nutrient deficiencies. Once the fish adapted to the novel feed, they started responding positively, indicating that poultry waste could serve not only as a supplementary feed but also as a sole feed in carp culture, provided the nutritional limitations are addressed.

CONCLUSION

The present study highlights the potential of utilizing poultry farm waste (PW) as the sole feed in the diet of rohu (Labeo rohita) fingerlings. Initially, the fish exhibited negative growth, likely due to acclimatization challenges and the differences in texture, taste, and nutritional composition of the PW compared to conventional feeds. Nutritional deficiencies, particularly low protein, fat, and vitamin content, further contributed to reduced growth during the initial phase. However, as the fish adapted to the PW feed, positive growth trends were observed, particularly after 40 days, with consistent weight gain by the end of the trial. This indicates that PW has the potential to be a viable feed option for carp culture when supplemented with essential nutrients. Despite its limitations, PW provides a cost-effective and sustainable alternative to traditional feeds. It also offers an environmentally friendly solution for recycling poultry waste, reducing its negative impact on ecosystems. Future research should focus on optimizing PW feed formulations by incorporating protein and vitamin supplements to enhance their nutritional profile. These findings suggest that PW, when used judiciously, could significantly contribute to sustainable aquaculture practice.

SIGNIFICANCE STATEMENT

This study demonstrates the potential of poultry farm waste (PW) as a cost-effective and sustainable feed alternative in aquaculture, specifically for Labeo rohita fingerlings. Despite initial growth setbacks due to acclimatization and nutritional deficiencies, fish fed with PW showed recovery and consistent weight gain after adaptation. The high dry matter and carbohydrate content in PW offer promising energy sources, while its moderate protein levels support its role as a partial or supplementary protein substitute. However, the elevated fiber and ash content may limit digestibility and require dietary balancing. The study also highlights the importance of optimizing feed formulations to improve growth performance, survivability, and feed conversion efficiency. These findings contribute to sustainable aquaculture practices by promoting waste recycling, reducing environmental burden, and lowering feed costs through innovative use of agricultural by-products.

REFERENCES

- Afroz, R., K. Hanaki and K. Hasegawa-Kurisu, 2009. Willingness to pay for waste management improvement in Dhaka City, Bangladesh. J. Environ. Manage., 90: 492-503.

- Faridullah, A. Waseem, A. Alam, M. Irshad, M.A. Sabir and M. Umar, 2012. Leaching and mobility of heavy metals after burned and unburned poultry litter application to sandy and masa soils. Bulg. J. Agric. Sci., 18: 733-741.

- Reimers, T.J., J.P. McCann and R.G. Cowan, 1983. Effects of storage times and temperatures on T3, T4, LH, prolactin, insulin, cortisol and progesterone concentrations in blood samples from cows. J. Anim. Sci., 57: 683-691.

- Cantrell, K.B., T. Ducey, K.S. Ro and P.G. Hunt, 2008. Lives stock waste-to-bioenergy generation opportunities. Bioresour. Technol., 99: 7941-7953.

- Owen, O.J., E.M. Ngodigha and A.O. Amakiri, 2008. Proximate composition of heat treated poultry litter (layers). Int. J. Poult. Sci., 7: 1033-1035.

- Craig, W.J., 2009. Health effects of vegan diets. Am. J. Clin. Nutr., 89: 1627S-1633S.

- Al-Asgah, N.A., 1999. Feeding different levels of dried poultry excreta on the growth performance and body composition of Oreochromis niloticus. Pak. Vet. J., 19: 7-12.

- Thiex, N., L. Novotny and A. Crawford, 2012. Determination of ash in animal feed: AOAC Official Method 942.05 revisited. J. AOAC Int., 95: 1392-1397.

- Abiola, S.S. and E.K. Onunkwor, 2004. Replacement value of hatchery waste meal for fish meal in layer diets. Bioresour. Technol., 95: 103-106.

- Ahmad, K., M. Hussain, M. Ashraf, M. Luqman, M.Y. Ashraf and Z.I. Khan, 2007. Indigenous vegetation of Soone Valley: At the risk of extinction. Pak. J. Bot., 39: 679-690.

- Ayoola, S.O., 2011. Haematological characteristics of Clarias gariepinus (Buchell, 1822) juveniles fed with poultry hatchery waste. Iran. J. Energy Environ., 2: 18-23.

- Nyina-Wamwiza, L., P.S. Defreyne, L. Ngendahayo, S. Milla, S.N.M. Mandiki and P. Kestemont, 2012. Effects of partial or total fish meal replacement by agricultural by-product diets on gonad maturation, sex steroids and vitellogenin dynamics of African catfish (Clarias gariepinus). Fish Physiol. Biochem., 38: 1287-1298.

- Zheng, Q., X. Wen, C. Han, H. Li and X. Xie, 2012. Effect of replacing soybean meal with cottonseed meal on growth, hematology, antioxidant enzymes activity and expression for juvenile grass carp, Ctenopharyngodon idellus. Fish Physiol. Biochem., 38: 1059-1069.

How to Cite this paper?

APA-7 Style

Ullah,

K., Aziz,

F., Hasan,

Z. (2025). Effects of Poultry Farm Waste on the Survival and Growth of Rohu (Labeo rohita). Trends in Biological Sciences, 1(4), 277-284. https://doi.org/10.21124/tbs.2025.277.284

ACS Style

Ullah,

K.; Aziz,

F.; Hasan,

Z. Effects of Poultry Farm Waste on the Survival and Growth of Rohu (Labeo rohita). Trends Biol. Sci 2025, 1, 277-284. https://doi.org/10.21124/tbs.2025.277.284

AMA Style

Ullah

K, Aziz

F, Hasan

Z. Effects of Poultry Farm Waste on the Survival and Growth of Rohu (Labeo rohita). Trends in Biological Sciences. 2025; 1(4): 277-284. https://doi.org/10.21124/tbs.2025.277.284

Chicago/Turabian Style

Ullah, Kalim, Fawad Aziz, and Zaigham Hasan.

2025. "Effects of Poultry Farm Waste on the Survival and Growth of Rohu (Labeo rohita)" Trends in Biological Sciences 1, no. 4: 277-284. https://doi.org/10.21124/tbs.2025.277.284

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.