Peanut Leaf Spot Disease Complex: Escalating Threats in the Era of Climate Change

| Received 31 Oct, 2025 |

Accepted 20 Jan, 2026 |

Published 31 Mar, 2026 |

Background and Objective: The rise in pathogenic species populations of significance to agriculture in arable land is projected to assume an upward trajectory across natural ecosystems in response to the foreseen climate change patterns, with notably dire repercussions on agricultural value chains. The leaf spot disease complex (early and late leaf spots) still ranks as the most significant foliar disease of peanut (Arachis hypogaea). Therefore, this study aimed to review the epidemiology of peanut leaf spot disease complex in the context of a changing climate and management recommendations. Materials and Methods: The study surveyed scholarly knowledge in several recently published research articles on a wide range of peanut phyto-pathological aspects. Relevant publications and secondary data were sourced from reputable journal websites, filtered to the scope of this study, synthesized, critiqued and analyzed using the authors’ vast experience. Results: Knowledge gaps still exist on the exact role of climate change parameters such as sporadic rainfall patterns, fluctuating temperature, elevated humidity in peanut leaf spot disease spread and, how their association with phyto-pathogenic ecologies affects crop health and natural biodiversity. Being cardinal peanut pathogens, detailed studies of Cercospora arachidicola and Cercosporidium personatum have revealed crucial aspects of their ecology in connection to peanut and symptoms of virulence thereafter. Conclusion: Accurate inference of the pathogens’ biology to the development of effective and sustainable management protocols is key to averting the huge losses incurred from the disease. Applied and adaptive research priorities should encompass major factors of disease establishment and development, such as soil microbial diversity and how they respond to the changing climate, thereby providing a strong scientific ground for innovations targeting disease prediction and control.

| Copyright © 2026 Odhiambo et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. |

INTRODUCTION

An upsurge in the global prevalence of agriculturally important plant diseases has exposed the human race to food and nutrition insecurity, food safety hazards and agro-ecological instability, which is most likely to trigger a rapid decline in agricultural productivity and natural biodiversity degradation, thereby negating the gains made in environmental conservation and socio-economic wellbeing of affected communities. Unstable and unpredictable weather patterns occasioned by climate change crisis continue to accelerate unprecedented plant disease pandemics through new patterns of host-pathogen interactions, genetic modification of existing pathogen strains and emergence of new pathogenic strains capable of successfully extending their virulence to traditionally resilient crop species. Global discussions on how climate change negatively impacts agriculture continue appreciating the need to prioritize climate smart agriculture (CSA) triple wins of productivity, adaptation and mitigation. This is generally perceived as a formidable approach towards realizing sustainable food and nutrition security in the glaring face of climate change menace. Experts estimate a 50 to 70% rise in demand for human food across the world by the year 2050, which is proportionate to the projected increase in human population likely to hit 9.6 billion by the same year. The exponential rise in phyto-pathogenic severity across different parts of the world remains a major threat to global food security and conservation of agro-biodiversity among farming communities which are largely dependent on vulnerable crop species1-3. Frequent infection of crop fields by diseases result in low yields and loss of agro-ecologies. Such a norm is poised to accelerate food supply crisis and natural plant biodiversity degradation4,5. Worth noting is the alarming rate at which high pathogenic infection rates continue to spread in key food and industrial crops such as peanuts. The fate of yield gains from peanut and other crops in the coming years will be influenced by climate change-triggered disease outbreaks associated with existing and emerging plant pathogens6. Therefore, advanced awareness of climate change risks and their impacts on the establishment of crop diseases in relation to how these biotic and abiotic forces interact remains key to the development of climate change-resilient agricultural ecosystems7,8.

Peanut (Arachis hypogaea L.), which is traditionally tolerant to weather adversities and a popular legume among arid and semi-arid communities9,10 is ranked fourth among the major oilseed crops globally11. The crop is laden with about 50% unsaturated fatty acids, approximately 28% simple protein, significant portions of vitamins and fairly sufficient levels of critical minerals, thus positioning itself as a nutritionally and economically valuable crop12. Previous studies have exposed leaf spot disease complex as a leading drawback to the production of peanut globally in addition to other biotic constrains13. In other words, the leaf spot disease complex (early and late leaf spots) associated with the fungi Cercospora arachidicola and Cercosporidium personatum respectively, still ranks as the deadliest foliar disease of Arachis hypogaea. In most cases, the manifestation of early and late leaf spot diseases may vary across the growth and development phases of peanut but due to their overlapping symptoms and effect on yield, field assessments and control strategies consider them as a single infection of leaf spot disease complex14. Severe infection of susceptible peanut cultivars by the leaf spot disease complex can result in significant yield losses of over 70%15. due to limited photosynthetic ability of infected plants and massive defoliation16. These effects may be more severe under extended warm and humid weather conditions17, as is currently being witnessed courtesy of climate change. The geographical location, peanut varieties cultivated, routine agronomic practices or changing seasonal weather patterns greatly influence leaf spot disease establishment on peanut as a disease complex or a single widespread infection18. Because a disease-free crop is the basis for a healthy food of high quality, averting peanut yield losses caused by leaf spot disease complex through counter-insurgency modus operandi is a desired gain. This review, therefore, provides a classical synthesis of current knowledge in peanut leaf spot disease complex under the escalating threat of climate change. It analyzes how shifting abiotic setbacks influence peanut leaf spot pathogen epidemiology, disease severity and host susceptibility. The review further seeks to outline critical

knowledge gaps in the understanding of this disease and assess the resilience of present-day management strategies. Hence, the anticipated contribution of this review is a consolidated framework to support the development of adaptive, sustainable and climate-resilient integrated leaf spot disease management protocols for peanut.

Taxonomy and morphological variations: The scientific classification of peanut leaf spot disease complex pathogens has evolved over the decades. After the original documentation of the genus Cercospora, subsequent placement of individual species into the corresponding taxonomic strata has not been a trivial task.

Contrary to the norm of heavily relying on sexual reproductive morphology as a major identification parameter for new fungal isolates, this trend has fallen short of distinguishing Cercospora spp. Consequently, the previous years of research have seen taxonomists through successful application of molecular tools in classification of Mycosphaerellaceae19-21. The old taxonomic tree of peanut leaf spot disease pathogens comprised the phylum Deuteromycotina Class: Hyphomycetes Order: Moniliales Family: Dematiaceae Genus: Cercospora/Cercosporidium Species: C. arachidicola/C. personatum. However, continued efforts by taxonomists to update the unique identities of various fungal pathogens of importance to agriculture has yielded a new taxonomic structure with Phylum: Ascomycota Class: Dothideomycetes Subclass: Dothideomycetidae Order: Capnodiales Family: Mycosphaerellaceae Genus: Cercospora (Mycosphaerella) Cercosporidium (Mycosphaerella) Species: C. arachidicola (M. arachidis) C. personatum (M. berkeleyi)22. Being cardinal peanut pathogens, detailed studies of these fungi have revealed crucial aspects of their ecology in connection to the host (peanut) and symptoms of virulence thereafter. Accurate inference of the pathogens’ biology to the development of effective and sustainable management protocols is key to averting the huge yield losses incurred from the disease. Among the priority biological elements of leaf spot disease complex fungi is their morphological variation. Fine to coarse, colored and septate hyphae usually form the mycelial body. The short, simple conidiophores do not have branches, are septate and either emerge from stromata or vegetative hyphae22. The hyphae form several light brown fascicles with darker bases. The conidiophores are common on the upper leaf surfaces in early leaf spot, as opposed to the case of late leaf spot where conidiophores are mostly observed on the lower side of foliage22. Shape-wise, the conidia of Cercospora arachidicola are curved and contain about 12 septa, with truncate bases and sub-acute ends. On the other hand, the conidia of Cercosporidium personatum are straight or relatively curved, cylindrical and, obclavate, with a coarse wall, round apex containing 3-4 septa. A shortly tapered base and a clearly visible hilum are the distinct features of these conidia22.

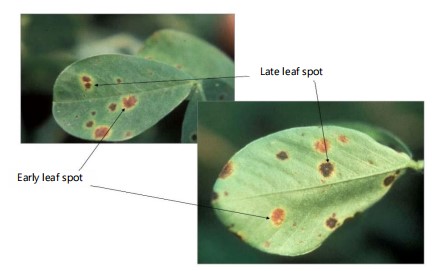

Symptomatology: Knowledge gaps still exist on the role of climate change parameters, such as unpredictable rainfall patterns, fluctuating temperature and elevated humidity and how their association with phyto-pathogenic ecologies affects crop health and natural biodiversity. For instance, the rise in crop myco-pathogenic species populations in arable soil is projected to assume an upward trajectory across natural ecosystems in response to the foreseen climate change patterns, with notably dire repercussions for agricultural value chains23. A clear understanding of the forms or patterns in which peanut leaf spot disease complex manifests is crucial to its identification and the application of climate-resilient management methods against it. Early leaf spot is largely associated with leaf-penetrating brown lesions (spots) visible on both leaf surfaces and are characteristically surrounded by yellow halos. The halos are, however, not distinct to early leaf spot and are therefore not diagnostic of this disease. The lesions of this fungal disease usually emerge as regular, rounded spots, but as the infection thrives, these spots expand and coalesce to form irregular patches on the infected leaf lamina. The infection also results in silvery, hair-like spore formations. Similar to other plant diseases, late leaf spot of peanut has a variety of distinct symptoms. The disease generally manifests as leaf-penetrating dark-brown to black lesions commonly visible on the upper and lower leaf surfaces. These lesions or spots are sometimes circled by a yellow halo.

|

While in their early stages of development, the lesions are seen as dark speckles, but upon maturity, they appear as rounded and dark brown to nearly black spots. Massive spore production by late leaf spot lesions is common under humid weather conditions. The masses of dark spores on the surface of lesions reveal a velvet-like appearance which is visible without the aid of magnification. As observed, lesion color is the main parameter of distinction between early and late leaf spots on peanut. While early leaf spot is characteristic of brown lesions, the late leaf spot is manifested through dark-brown-to-black lesions common on the lower leaf surface. Initially, the symptoms of both diseases appear on mature foliage at the base of the stem before advancing to the upper canopy of the crop. Progressive leaf fall occasioned by the infection then follows beginning with lower mature leaves upwards to the entire foliage causing total defoliation and desiccation especially where susceptible peanut varieties are involved or under severe infection. In such cases, it’s also possible to observe lesions on bare branches and stems as shown in Fig.1.

When the dead decaying foliage that hosts pathogen strains remains on the soil surface under moist and humid conditions, it provides substrate for sporulation, thereby forming a great source of inoculum for subsequent seasons. This becomes detrimental if the former and current peanut crops are established on the same soils14. Typically, the distinction between the spots of these two phyto-fungal infections and those initiated by pesticide injuries is very dismal, more so in the early stages of disease development. Whenever the prevailing weather conditions remain conducive for sustained virulence, regeneration of lesions with large masses of spores occurs. This trend is commonly observed within ten to fourteen days of a previous infection. For accurate laboratory and field diagnosis, spores must be clearly observed on the upper surface of a developing lesion for early leaf spot and on the lower surface of lesions corresponding to late leaf spot. Where disease presence is suspected, but infected or symptomatic leaves lack spores, such leaves can be incubated in a moist chamber at about 26 to 28°C for 24 to 48 hrs before spores grow and become visible under low magnification. High temperatures have been reported to shorten the incubation period of phyto-pathogens, thereby increasing their population, virulence and severity.

Peanut farmers who practice short crop rotation sequences, for instance, one or two consecutive seasons in fields that are historically associated with severe leaf spot disease complex infections usually face the biggest threat of huge yield losses. Preservation of volunteer peanut plants during weeding or volunteer rotation crops encourages the growth of latent leaf spot infections and rapid disease development, especially under warm weather conditions when humidity rises above 90% and is sustained for several hours. Under such conditions, the pathogen virulence can be triggered during the night and the severity of infection gets accelerated in the humid morning hours. The prevalence of peanut leaf spot disease has been reported to rise under extended wet conditions precipitated by prolonged rains. Conversely, other reports also point to the possibility of disease outbreak in dry spells characterized by humid conditions and high dew accumulation. Disease incubation mostly occurs in edges with dense canopy and low-lying sections of peanut crop fields, where the duration of foliage wetness and relative humidity are likely to be long. These conditions can also result from irrigation methods that encourage prolonged foliage wetness, such as overhead irrigation. Additionally, excessive presence of nitrogen as a nutrient element can encourage the emergence of lush foliage, thereby increasing canopy moisture concentration, which predisposes the crop to leaf spot disease infection. Planting peanut crop fields late into the season also enhances the risk of huge losses due to severe infection, since the routine changes in weather patterns witnessed as the season progresses are usually pro-disease establishment.

Pathogen survival and disease spread: The establishment and development of peanut leaf spot disease complex is a factor of how the responsible pathogens survive from one season to another, more so when the prevailing abiotic elements are unfavorable. This complex process also relies on the mechanism of disease transmission or pathogen disposal from infected to uninfected hosts. In order for peanut leaf spot infection to successfully occur, the survival and subsequent transmission of virulent Cercospora arachidicola and Cercosporidium personatum strains must be aided by the presence of susceptible hosts in a conducive environment. These pathogens remain virulent across seasons by maintaining a complete infection chain, which largely depends on the frequency of host plant reinfection. In certain instances, reinfection may extend to other plants of the same species as the peanut. Such plant species are referred to as alternative hosts and range from several legumes to weeds. Immediately after harvesting, when temperature, moisture and humidity are optimum, peanut crop debris and residue incubate conidia bodies of Cercospora arachidicola and Cercosporidium personatum which form the primary inoculum. Mycelial growths on stems or petioles exhibit higher chances of survival and spread compared to similar growths on the foliage24.

Disease management: Global rise in temperature has significantly contributed to increased virulence among plant pathogens of agricultural importance, including Cercospora arachidicola and Cercosporidium personatum. Noteworthy, is the reality of these pathogens being able to colonize host plants beyond the ability of certain control measures to cope. The successful containment of peanut leaf spot disease complex results from a significant reduction in spore production through a plethora of eco-friendly integrated control measures. Over the years, the tendency of targeted pathogens to develop pesticide resistance is an eminent challenge to peanut leafspot disease management. In addition, farmers have contributed to the rising food safety and environmental hazards by prolonged use of synthetic fungicides in controlling peanut leaf spot disease complex. We explore a raft of eco-friendly non-chemical based options for the management of this disease.

Genetic resistance approach: In general terms, plants with genetic abilities to impede pathogen entry and disease development are defined as disease resistant25. Breeding for resistance has been extensively adopted as an effective approach to controlling diseases in annual and biennial crops26-28. For instance, the identification of early and late leaf spot disease resistant genotypes from pools of breeding germplasm, registered cultivars and wild species genetically related to peanut by breeders and pathologists has been reported as a milestone in the quest for sustainable management of the disease15,29. These gains are attributed to genetic adjustments geared towards inducing resistance to the diseases within targeted plant species26,28,30. Recent studies on genetic resistance have reported up to 60% yield increase from peanut leaf spot disease complex resistant varieties15,29,31,32. It is therefore a commendable approach to managing leaf spot disease complex and increasing yields.

Cultural practices: Under conventional and improved farming systems, peanut producers characteristically undertake a series of routine operations to manage biotic constraints i.e. diseases. These operations constitute cultural practices and include but are not limited to weeding, correct plant population, crop rotation, use of high quality seed, integrated soil fertility and water management, timely planting, rouging, use to tolerant varieties and soil treatment via solarization33,34. A case in point is the role of phyto-sanitary practices in the control of peanut early leaf spot disease35-37. Cultural operations also reduce phyto-pathogen populations by facilitating the ecological process of antagonistic microbiota in the soil38. The application of cultural practices solely or as an integrated package depends on the type of crop in question, the type of disease and prevailing environmental conditions. Nonetheless, the combined and simultaneous application of cultural operations on a target disease has been reported as more effective and economically sound33. A strong determinant of how best cultural practices work to contain peanut leaf spot disease complex is the farmers’ experience with the crop. For instance, knowledge of the most suitable crop species for inclusion in a rotation sequence undoubtedly influences the success of disease control39. Expert opinion suggests the use of crops that do not share the same family as the peanut for effective crop rotation. Formidable examples of best-bet-crops for rotation with peanut in a three-year program include sorghum, millet and maize33,38,40. Plant species from the same family as the peanut can successfully host and spread peanut leaf spot disease complex pathogens.

Biological control: This method encompasses the control of phytopathogens such as Cercospora arachidicola and Cercosporidium personatum through a deliberate release of living organisms with either an antagonistic effect or a competitive advantage over them41,42. A wide variety of antagonistic species, such as certain strains of rhizobacteria, have been identified and successfully used in the management of peanut leaf spot disease complex. In addition, Lecanicillium lecanii43, strains of Dicyma pulvinata and Verticillium lecanii44 have demonstrated significant levels of efficacy in the control of peanut leaf spot disease complex pathogens. Integrated soil fertility management practices, which enhance soil organic matter content, support the ecological wellbeing of antagonistic microbiota, which in turn suppresses the population of Cercospora arachidicola and Cercosporidium personatum45. The potency of antagonistic microbes as biocontrol tools for suppression of plant disease pathogens also has a strong nexus with the prehistoric agronomic practice of rotating crops to break disease cycles and contain pathogen populations46. This affirms the need to integrate biological control into cultural practices if an impactful management of Cercospora arachidicola and Cercosporidium personatum is to be achieved. In some instances, however, biological management of peanut leaf spot disease complex continues to attract the global interest of crop health experts due to its notable efficacy as a sole component43.

CONCLUSION

Stakeholders in the agriculture sector across the world are gradually coming to terms with the reality that climate change crisis is likely to accelerate plant disease establishment and development. Consequently, it behooves crop health experts to gain more insights on the ecology and epidemiology of economically significant phyto-pathogens such as Cercospora arachidicola and Cercosporidium personatum. This would help in unpacking the complexities of infection severity and its economic impacts so as to develop timely disease prediction, monitoring, detection and management tools. Considering the significant threat of peanut leaf spot disease complex to food and nutrition security and the emerging consensus on hazards associated with pesticide use in controlling the disease, necessary efforts should be geared towards environmentally sound strategies. Applied and adaptive research priorities should encompass major factors of disease establishment and development such as soil microbial diversity and how they respond to the changing climate, thereby providing a strong scientific ground for innovations targeting disease prediction and control. A well-guided approach in understanding the epidemiology of peanut leaf spot disease complex will potentially avert the huge yield losses through proper application of disease management recommendations. Likewise, incorporating the pre-existing climate-change-related knowledge on disease pathogen vectors into disease management studies can enhance the prompt projection of future disease outbreaks.

SIGNIFICANCE STATEMENT

Climate change is expected to accelerate the spread and severity of peanut leaf spot disease, posing a serious threat to global food and nutrition security. By examining the epidemiology of Cercospora arachidicola and Cercosporidium personatum under shifting climatic conditions, this review identifies critical knowledge gaps on pathogen ecology, infection dynamics and disease progression. The study emphasizes the need for climate-responsive, sustainable disease management strategies and highlights soil microbial diversity as a key research priority for developing reliable disease prediction and control innovations.

REFERENCES

- Fones, H.N., D.P. Bebber, T.M. Chaloner, W.T. Kay, G. Steinberg and S.J. Gurr, 2020. Threats to global food security from emerging fungal and oomycete crop pathogens. Nat. Food, 1: 332-342.

- Ristaino, J.B., P.K. Anderson, D.P. Bebber, K.A. Brauman and N.J. Cunniffe et al., 2021. The persistent threat of emerging plant disease pandemics to global food security. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A., 118.

- Tripathi, H.G., W.E. Kunin, H.E. Smith, S.M. Sallu and S. Maurice, et al., 2022. Climate-smart agriculture and trade-offs with biodiversity and crop yield. Front. Sustainable Food Syst., 6.

- Burdon, J.J. and J. Zhan, 2020. Climate change and disease in plant communities. PLoS Biol., 18.

- Singh, B.K., M. Delgado-Baquerizo, E. Egidi, E. Guirado, J.E. Leach, H. Liu and P. Trivedi, 2023. Climate change impacts on plant pathogens, food security and paths forward. Nat. Rev. Microbiol., 21: 640-656.

- Muluneh, M.G., 2021. Impact of climate change on biodiversity and food security: A global perspective-a review article. Agric. Food Secur., 10.

- Chaloner, T.M., S.J. Gurr and D.P. Bebber, 2021. Plant pathogen infection risk tracks global crop yields under climate change. Nat. Clim. Change, 11: 710-715.

- Rohr, J.R., C.B. Barrett, D.J. Civitello, M.E. Craft and B. Delius et al., 2019. Emerging human infectious diseases and the links to global food production. Nat. Sustainability, 2: 445-456.

- van Dijk, M., T. Morley, M.L. Rau and Y. Saghai, 2021. A meta-analysis of projected global food demand and population at risk of hunger for the period 2010-2050. Nat. Food, 2: 494-501.

- Zheng, Z., Z. Sun, Y. Fang, F. Qi and H. Liu et al., 2018. Genetic diversity, population structure, and botanical variety of 320 global peanut accessions revealed through tunable genotyping-by-sequencing. Sci. Rep., 8.

- El-Metwally, I.M., M.S. Sadak and H.S. Saudy, 2022. Stimulation effects of glutamic and 5-aminolevulinic acids on photosynthetic pigments, physio-biochemical constituents, antioxidant activity, and yield of peanut. Gesunde Pflanzen, 74: 915-924.

- Zanjare, S.R., A.V. Suryawanshi, S.S. Zanjare, V.R. Shelar and Y.S. Balgude, 2023. Screening of groundnut (Arachis hypogaea L.) genotypes for identification of sources of resistance against leaf spot disease. Legume Res., 46: 288-294.

- Bakry, B.A., M.S. Sadak and A.A. Abd El-Monem, 2020. Physiological aspects of tyrosine and salicylic acid on morphological, yield and biochemical constituents of peanut plants. Pak. J. Biol. Sci., 23: 375-384.

- Chu, Y., P. Chee, A. Culbreath, T.G. Isleib, C.C. Holbrook and P. Ozias-Akins, 2019. Major QTLs for resistance to early and late leaf spot diseases are identified on chromosomes 3 and 5 in peanut (Arachis hypogaea). Front. Plant Sci., 10.

- Anco, D.J., J.S. Thomas, D.L. Jordan, B.B. Shew and W.S. Monfort et al., 2020. Peanut yield loss in the presence of defoliation caused by late or early leaf spot. Plant Dis., 104: 1390-1399.

- Mohammed, K., E. Afutu, T. Odong, D. Okello and E. Nuwamanya et al., 2018. Assessment of groundnut (Arachis hypogaea L.) genotypes for yield and resistance to late leaf spot and rosette diseases. J. Exp. Agric. Int., 21.

- Jordan, B.S., A.K. Culbreath, T.B. Brenneman, R.C. Kemerait and W.D. Branch, 2017. Late leaf spot severity and yield of new peanut breeding lines and cultivars grown without fungicides. Plant Dis., 101: 1843-1850.

- McDonald, D., 1985. Early and Late Leaf Spots of Groundnut. International Crops Research Institute for the Semi-Arid Tropics, India, Pages: 19.

- Cantonwine, E.G., A.K. Culbreath, C.C. Holbrook and D.W. Gorbet, 2008. Disease progress of early leaf spot and components of resistance to Cercospora arachidicola and Cercosporidium personatum in runner-type peanut Cultivars. Peanut Sci., 35: 1-10.

- Groenewald, J.Z., C. Nakashima, J. Nishikawa, H.D. Shin and J.H. Park et al., 2013. Species concepts in Cercospora: Spotting the weeds among the roses. Stud. Mycol., 75: 115-170.

- Crous, P.W., U. Braun, G.C. Hunter, M.J. Wingfield and G.J.M. Verkley et al., 2013. Phylogenetic lineages in Pseudocercospora. Stud. Mycol., 75: 37-114.

- Guatimosim, E., P.B. Schwartsburd, R.W. Barreto and P.W. Crous, 2016. Novel fungi from an ancient niche: Cercosporoid and related sexual morphs on ferns. Persoonia Mol. Phylog. E Fungi, 37: 106-141.

- Dastogeer, K.M.G., J. Kao-Kniffin and S. Okazaki, 2022. Editorial: Plant microbiome: Diversity, functions, and applications. Front. Microbiol., 13.

- Delgado-Baquerizo, M., C.A. Guerra, C. Cano-Díaz, E. Egidi and J.T. Wang et al., 2020. The proportion of soil-borne pathogens increases with warming at the global scale. Nat. Clim. Change, 10: 550-554.

- Pati, R., S. Sandhu, A.K. Kawadiwale and G. Kaur, 2025. Unveiling the underlying complexities in breeding for disease resistance in crop plants: Review. Front. Plant Sci., 16.

- Mores, A., G.M. Borrelli, G. Laidò, G. Petruzzino, N. Pecchioni et al., 2021. Genomic approaches to identify molecular bases of crop resistance to diseases and to develop future breeding strategies. Int. J. Mol. Sci., 22.

- Bhat, R.S., Venkatesh, M.P. Jadhav, P.V. Patil and K. Shirasawa 2022. Genomics-Assisted Breeding for Resistance to Leaf Spots and Rust Diseases in Peanut. In: Accelerated Plant Breeding, Volume 4: Oil Crops, Gosal, S.S. and S.H. Wani (Eds.), Springer International Publishing, Switzerland, ISBN: 978-3-030-81107-5, pp: 239-278.

- Codjia, E.D., B. Olasanmi, P.A. Agre, R. Uwugiaren, A.D. Ige and I.Y. Rabbi, 2022. Selection for resistance to cassava mosaic disease in African cassava germplasm using single nucleotide polymorphism markers. S. Afr. J. Sci., 118.

- Chaudhari, S., D. Khare, S.C. Patel, S. Subramaniam and M.T. Variath et al., 2019. Genotype×environment studies on resistance to late leaf spot and rust in genomic selection training population of peanut (Arachis hypogaea L.). Front. Plant Sci., 10.

- Kankam, F., K.Y. Kojo and I.K. Addai, 2020. Evaluation of groundnut (Arachis hypogea L.) mutant genotypes for resistance against major diseases of groundnut. Pak. J. Phytopathol., 32: 61-69.

- Denwar, N.N., C.E. Simpson, J.L. Starr, T.A. Wheeler and M.D. Burow, 2021. Evaluation and selection of interspecific lines of groundnut (Arachis hypogaea L.) for resistance to leaf spot disease and for yield improvement. Plants, 10.

- de Paul N’Gbesso, M.F., A.A.G. Gadji, N.D. Coulibaly, B.U. Kogloin and L. Fondio et al., 2024. Assessment of the agronomic performance of twenty-two (22) peanut (Arachis hypogaea L.) accessions against late leaf spot and groundnut rosette diseases in central Côte d’Ivoire. Cogent Food Agric., 10.

- Rani, A., R. Singh, P. Kumar and G. Shukla, 2017. Pros and cons of fungicides: An overview. Int. J. Eng. Sci. Res. Technol., 6: 112-117.

- Branch, W.D., I.N. Brown and A.K. Culbreath, 2021. Planting date effect upon leaf spot disease and pod yield across years and peanut genotypes. Peanut Sci., 48: 49-53.

- Mugisa, I.O., J. Karungi, B. Akello, M.K.N. Ochwo-Ssemakula, M. Biruma, D.K. Okello and G. Otim, 2016. Determinants of groundnut rosette virus disease occurrence in Uganda. Crop Prot., 79: 117-123.

- Seidu, A., M. Abudulai, I. Dzomeku, G. Mahama and J. Nboyine et al., 2024. Evaluation of production and pest management practices in peanut (Arachis hypogaea) in Ghana. Agronomy, 14.

- Brenneman, T.B., D.R. Sumner, R.E. Baird, G.W. Burton and N.A. Minton, 1995. Suppression of foliar and soilborne peanut diseases in bahiagrass rotations. Phytopathology, 85: 948-952.

- Lucas, G.B., C.L. Campbell and L.T. Lucas, 1992. Introduction to Plant Diseases: Identification and Management. 2nd Edn., Springer, New York, ISBN: 978-1-4615-7294-7, Pages: 100.

- Woo, S.L., F. de Filippis, M. Zotti, A. Vandenberg, P. Hucl and G. Bonanomi, 2022. Pea-wheat rotation affects soil microbiota diversity, community structure, and soilborne pathogens. Microorganisms, 10.

- Jalli, M., E. Huusela, H. Jalli, K. Kauppi, M. Niemi, S. Himanen and L. Jauhiainen, 2021. Effects of crop rotation on spring wheat yield and pest occurrence in different tillage systems: A multi-year experiment in Finnish growing conditions. Front. Sustainable Food Syst., 5.

- Richard, B., A. Qi and B.D.L. Fitt, 2021. Control of crop diseases through Integrated crop management to deliver climate‐smart farming systems for low- and high-input crop production. Plant Pathol., 71: 187-206.

- Morin, L., 2020. Progress in biological control of weeds with plant pathogens. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol., 58: 201-223.

- Tariq, M., A. Khan, M. Asif, F. Khan, T. Ansari, M. Shariq and M.A. Siddiqui, 2020. Biological control: A sustainable and practical approach for plant disease management. Acta Agric. Scand. Sect. B-Soil Plant Sci., 70: 507-524.

- Nana, T.A., A. Zongo, B.F. Neya and P. Sankara, 2022. Assessing the effects of Lecanicillium lecanii in the biological control of early and late leaf spot of peanut in vitro (Burkina Faso, West Africa). Afr. J. Agric. Res., 18: 1-7.

- Subrahmanyam, P., P.M. Reddy and D. McDonald, 1990. Parasitism of rust, early and late leafspot pathogens of peanut by Verticillium lecanii. Peanut Sci., 17: 1-4.

- Acharya, L.K., R. Balodi, K.V. Raghavendra, M. Sehgal and S.K. Singh, 2021. Diseases of groundnut and their eco-friendly management. Biotica Res. Today, 3: 806-809.

How to Cite this paper?

APA-7 Style

Odhiambo,

H., Orayo,

M., Ndung’u,

J.N., Kamau,

E. (2026). Peanut Leaf Spot Disease Complex: Escalating Threats in the Era of Climate Change. Trends in Biological Sciences, 2(1), 24-32. https://doi.org/10.21124/tbs.2026.24.32

ACS Style

Odhiambo,

H.; Orayo,

M.; Ndung’u,

J.N.; Kamau,

E. Peanut Leaf Spot Disease Complex: Escalating Threats in the Era of Climate Change. Trends Biol. Sci 2026, 2, 24-32. https://doi.org/10.21124/tbs.2026.24.32

AMA Style

Odhiambo

H, Orayo

M, Ndung’u

JN, Kamau

E. Peanut Leaf Spot Disease Complex: Escalating Threats in the Era of Climate Change. Trends in Biological Sciences. 2026; 2(1): 24-32. https://doi.org/10.21124/tbs.2026.24.32

Chicago/Turabian Style

Odhiambo, Harun, Mercyline Orayo, John N. Ndung’u, and Elias Kamau.

2026. "Peanut Leaf Spot Disease Complex: Escalating Threats in the Era of Climate Change" Trends in Biological Sciences 2, no. 1: 24-32. https://doi.org/10.21124/tbs.2026.24.32

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.