Comparative Analysis of Vitamin, Amino Acid, and Fatty Acid Profiles in Pleurotus ostreatus Cultivated on Iron-Fortified Wood Substrates

| Received 15 Oct, 2025 |

Accepted 22 Jan, 2026 |

Published 31 Mar, 2026 |

Background and Objective: Iron deficiency and protein-energy malnutrition remain widespread in developing regions, necessitating affordable dietary interventions. Pleurotus ostreatus (oyster mushroom) offers potential as a functional food due to its rich nutrient composition. This study investigated how iron fortification of different tropical wood substrates influences the vitamin, amino acid, and fatty acid profiles of P. ostreatus. Materials and Methods: The experiment involved six treatment groups using three tropical wood substrates (Canarium sp., Ceiba pentandra, and Pycnanthus angolensis), each with iron-fortified and non-fortified variants. Standard analytical methods were used to determine vitamin, amino acid, and fatty acid contents. The data were analyzed using ANOVA, and treatment means were compared with Duncan’s Multiple Range Test, with the t-value evaluated at a 95% confidence interval. Results: Vitamin content varied significantly across treatments. Mushrooms cultivated on non-fortified Pycnanthus angolensis recorded the highest vitamin A level (8.08 mg/100 g), while iron-fortified samples on the same substrate exhibited the highest vitamin C content (204.91 mg/100 g). Glutamic acid was the most abundant amino acid, reaching 10.70/100 g in fortified Pycnanthus samples. Essential amino acids such as leucine (2.37/100 g), arginine (6.32/100 g), and alanine (3.77/100 g) were also elevated with fortification. Fatty acid analysis showed oleic (33.95%) and palmitic acids (29.30%) as the most prevalent, with higher concentrations in fortified mushrooms. Conclusion: Iron fortification significantly enhanced the vitamin, amino acid, and fatty acid composition of P. ostreatus, particularly when cultivated on Pycnanthus angolensis. The fortified mushrooms demonstrate strong potential for improving iron and protein intake in resource-limited populations.

| Copyright © 2026 Oyetayo and Ariyo. This is an open-access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. |

INTRODUCTION

Mushrooms have long been recognized as nutritious, functional foods with significant potential for addressing malnutrition, especially in resource-limited settings. Among cultivated species, Pleurotus ostreatus (the oyster mushroom) stands out for its efficient growth on agricultural and forestry residues, its rich profile of vitamins, minerals, amino acids, and fatty acids, and its capacity to bioaccumulate micronutrients when cultivated on supplemented substrates1,2.

The global burden of malnutrition, particularly micronutrient deficiencies such as iron deficiency anemia, continues to threaten public health, especially in developing regions3. Iron is an essential mineral critical for oxygen transport, immune function, and cellular metabolism, yet it remains one of the most common nutrient deficiencies worldwide4. In response to this challenge, researchers have been exploring sustainable and food-based approaches to enhance micronutrient intake among vulnerable populations. Among the promising strategies is the mineral element enrichment of edible fungi like Pleurotus ostreatus, commonly known as the oyster mushroom5,6.

Pleurotus ostreatus is valued not only for its culinary appeal and ecological sustainability but also for its rich nutritional profile, including essential vitamins, amino acids, and unsaturated fatty acids7,8. Pleurotus mushrooms are widely consumed due to their attractive taste, aroma, with nutritional and medicinal values9. It is a fleshy fungus with spore spore-bearing fruiting body belonging to the family Pleurotacaea, and the second largest cultivated mushroom. Its ability to grow on lignocellulosic agricultural and forestry wastes makes it an economically viable crop, especially in low-resource settings. Nutritional composition of Pleurotus ostreatus can vary depending on environmental factors such as temperature and substrate type10. This fungus can absorb mineral elements and bioaccumulate them as functional organic11. More importantly, its mycelial network has demonstrated the capacity to absorb and accumulate minerals from the growth substrate12, making it a suitable candidate for nutrient fortification.

However, there is still scanty information on the effect of substrate modification with mineral elements such as iron, zinc and selenium on the fatty acid and other contents of Pleurotus ostreatus is limited13. Previous studies reported the influence of mineral enrichment on the nutritional profile of mushrooms, but there remains limited literature on how iron fortification specifically affects the vitamin, amino acid, and fatty acid content of P. ostreatus cultivated on various tropical wood substrates. Understanding these interactions is crucial for optimizing mushroom-based interventions against malnutrition. This study, therefore, investigates the influence of iron fortification on the vitamins, amino acids, and fatty acids composition of P. ostreatus cultivated on wood substrates fortified with iron.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study area: This study was carried out in the Department of Microbiology, Federal University of Technology, Akure, Nigeria. Pleurotus ostreatus was cultivated on different wood substrates between the months of June and August, 2024.

Substrate preparation and cultivation of Pleurotus ostreatus: Pleurotus ostreatus was cultivated for several weeks on the sawdust obtained from Canarium sp., Ceiba pentandra, and Pycnanthus angolensis. The dry substrates were checked for consistency and were mixed thoroughly with water. The substrates were moistened with water to prevent dryness. About 800 g of medium was filled into polypropylene bags and sealed using paper and polyvinyl rings. The substrates in bags were sterilized in the autoclave and were left to cool down to ambient room temperature.

Fortification of Pleurotus ostreatus with zinc chloride: Eight milliliters of Ferrous sulphate (FeSO4) at a concentration of 50 mg/kg was injected to the bags containing substrates for iron fortification. A control treatment with no ferrous sulphate was also prepared14. Following this, substrates in separate bags were inoculated with 30 g of spawn. The bags were kept in the dark room with a relative humidity of 75% to maintain.

The growth of mycelium in each bag was observed. Once the mycelium fully covered the Substrate, the bags were left open in the growing house to allow fruit body formation. The mushroom fruit bodies were harvested, air-dried, and then ground into powder using a grinding machine (Lexmark Mixer Grinder KP- 4055).

Determination of the vitamins A and C content of cultivated Pleurotus ostreatus: Vitamin A and C content was determined according to the method of Achikanu et al.15. The mushroom samples were collected and thoroughly cleaned to remove soil and debris. They were freeze-dried to preserve vitamin content. The freeze-dried mushrooms were ground into a fine powder and stored in airtight containers at -20°C until analysis.

Vitamin A extraction: One gram of the powdered sample was weighed and added to 25 mL of ethanol, and homogenized for 2 min. A 25 mL of hexane was added and shaked for 5 min. The upper hexane layer was collected in separate phases, and the hexane was evaporated under reduced pressure, and the residue was reconstituted in methanol16.

Vitamin C extraction: One gram of the powdered sample was weighed and added to 50 mL of 0.1 M HCl, and homogenized for 2 min. A 25 mL of hexane was added and shaken for 5 min. It was heated in a water bath at 95°C for 30 min and centrifuged at 5000 rpm for 10 min, and the supernatant was collected17.

Determination of the vitamins A and C content of cultivated Pleurotus ostreatus: Standard solutions for vitamins A and C were prepared. The extracts were injected into a High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) system with UV/Vis detector at 265 nm for vitamin A and 254 nm for vitamin C. Retention times and peak areas were compared with standards to determine concentrations. The LC-MS was used for precise quantification and confirmation. Mass Spectrometry (MS) parameters were optimized for each vitamin18. Quality control was performed with standard solutions and blanks. Methods for linearity, accuracy, precision, and sensitivity was validated19. Triplicate analyses for reproducibility were conducted. Vitamin content was calculated using calibration curves from standards and the results expressed as mg or μg per 100 g of dry mushroom weight.

Fatty acid analysis of cultivated P. ostreatus: Fatty acids were determined by gas-liquid chromatography with flame ionization detection (GLC-FID)/capillary column based on the ISO 5509 (2000) trans-esterification method. The analysis was conducted using a split-splitless injector, a FID, and a Chrompack CP-9050 autosampler. The injector and detector temperatures were both set to 250°C. A 50 m×0.25 mm i.d. fused silica capillary column coated with a 0.19 μm film of CP-Sil 88 (Chrompack) was used for separation. Helium was employed as the carrier gas at an internal pressure of 120 kPa. The column temperature was initially set at 140°C for 5 min and then programmed to increase to 220°C at a rate of 4°C/min, where it was held for 10 min. The split ratio was 1:50, and the injected volume was 1.2 μL. The results are expressed as the relative percentage of each fatty acid, calculated by internally normalizing the chromatographic peak area. Fatty acid identification was performed by comparing the relative retention times of FAME peaks from samples with standards. A Supelco (Bellefonte, PA) mixture of 37 FAMEs (standard 47885-U) was utilized, and some fatty acid isomers were identified using individual standards also obtained from Supelco following the procedure of Barros et al.16.

Total amino acid analysis of cultivated mushrooms: The mushroom sample (1-3 g) was hydrolyzed under nitrogen gas with 10 mL of 4 N NaOH and 200 μg of ascorbic acid as an antioxidant in an autoclave at 110°C for 16 hrs and adjusted to pH 9.00. The hydrolysate was then filtered through a 0.45 μm cellulose acetate membrane filter before being injected into the HPLC for analysis. The amino acid composition was determined using reversed-phase HPLC and gradient elution20. The analysis was performed using the Agilent 1100 HPLC system (Agilent Technologies) with an autosampler, a Zorbax-Eclipse XDB-C18 column (4.6×150 mm, 5 μm) with a Zorbax Eclipse -AAA guard column ( 4.6×15.5 mm, μm) and a fluorescence detector. Chemstation Rev.A.09.03 (1417) (Agilent Technologies 1990-2002) was used for data acquisition and analysis. The sample was subjected to automatic pre-column derivatization with a combination of OPA-3MPA for primary amino acids and FMOC for secondary amino acids. Mobile phase A contains 40 mmoL/L Na2HPO4 at pH 7.8 and B contains 45% acetonitrile, 45% methanol, and 10% deionized water. The temperature of the chromatographic column was set at 40°C with a flow rate of 2 mL/min. The detector was set to 340/450 (Ex/Em) at 0 min and 266/305 (Ex/Em) at 15 min.

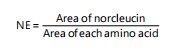

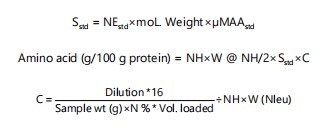

Calculation of amino acid values from the chromagram peaks: The net height of each peak produced by the TSM chart recorder (each representing one amino acid) was measured following Horwitz and Latimer21 procedure. The half-height of the peak on the chart was found, and the width of the peak at half height was accurately measured and recorded. The approximate area of each peak was calculated by multiplying the height by the width at half height. The nor leucine equivalent (NE) for each amino acid in the standard mixture was calculated using the formula:

|

A constant (S) was calculated for each amino acid in the standard mixture:

|

where:

| NH | = | Net height | |

| W | = | Width at half height | |

| Nleu | = | Norcleucine | |

| MAA | = | Molar absorption coefficient of the amino acid standard |

Statistical analysis of data: The data obtained were subjected to statistical Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) and Duncan’s Multiple Range Test was used to compare means. The ‘t’ value was tested at 95% confidence interval.

RESULTS

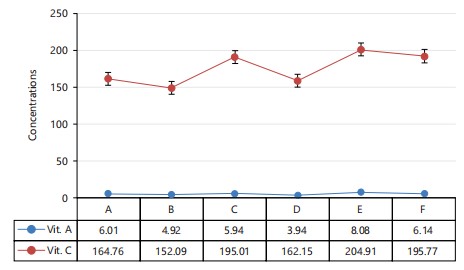

Non-iron fortified P. ostreatus cultivated on Pycnanthus angolensis has the highest vitamin A (8.08 mg/100 g) and vitamin C (204.91 mg/100 g) contents, as shown in Fig. 1. There are notable variations in the levels of both vitamins across the different samples.

Table 1 shows the amino acid content of the cultivated Pleurotus ostreatus. Glutamic acid was the highest amino acid recorded and the values range from 9.07 to 10.70/100 g, with iron fortified P. ostreatus cultivated on the wood substrate Pycnanthus angolensis recording the highest value of 10.70 g/100 g.

Fatty acid content (%) of cultivated mineral fortified and non-mineral fortified P. ostreatus: Table 2 shows the variations in the fatty acid content in all the samples. Palmitic acid content was significantly high in fortified P. ostreatus (B, D and F), but the highest value was recorded in P. ostreatus cultivated on non-fortified wood substrate (Pycnanthus angolensis). Oleic have the highest value of 33.33% in P. ostreatus cultivated on wood substrate (Canarium sp.) fortified with iron. This suggests that both substrate type and micronutrient fortification influence the accumulation of specific fatty acids.

|

| Table 1: | Amino acid composition (g/100 g) of cultivated mineral fortified and non-mineral fortified P. ostreatus | |||

| Amino acid | A | B | C | D | E | F |

| Alanine | 3.56±0.09a | 3.53±0.02a | 3.56±0.03a | 3.58±0.02a | 3.76±0.03b | 3.77±0.01b |

| Arginine | 5.04±0.02a | 5.03±0.02a | 5.75±0.02b | 5.76±0.02b | 6.30±0.02c | 6.32±0.03c |

| Aspartic acid | 3.82±0.02a | 3.83±0.03a | 4.10±0.02b | 4.10±0.01b | 4.32±0.03b | 4.39±0.01b |

| Cystine | 0.47±0.02a | 0.48±0.01a | 0.54±0.02b | 0.53±0.03b | 0.54±0.01b | 0.55±0.02b |

| Glutamic acid | 9.09±0.02a | 9.07±0.03a | 9.94±0.01b | 9.93±0.02b | 10.40±0.20c | 10.70±0.20c |

| Glycine | 0.44±0.02a | 0.45±0.02a | 1.54±0.03b | 1.53±0.01b | 1.64±0.02c | 1.67±0.02c |

| Histidine | 1.05±0.02a | 1.04±0.02a | 1.13±0.03b | 1.11±0.01b | 1.12±0.03b | 1.12±0.03b |

| Isoleucine | 1.12±0.03a | 1.12±0.02a | 1.21±0.02a | 1.22±0.02a | 1.24±0.02a | 1.29±0.03a |

| Leucine | 1.77±0.02a | 1.76±0.01a | 2.19±0.02b | 2.17±0.02b | 2.33±0.02b | 2.37±0.02b |

| Lysine | 1.42±0.02a | 1.41±0.03a | 1.44±0.02a | 1.44±0.03a | 1.48±0.02a | 1.52±0.03b |

| Methionine | 0.48±0.01a | 0.43±0.03a | 0.44±0.02a | 0.45±0.02a | 0.55±0.02b | 0.54±0.03b |

| Phenylalanine | 1.28±0.02a | 1.31±0.02b | 1.45±0.01c | 1.45±0.02c | 1.28±0.02a | 1.30±0.02b |

| Proline | 0.44±0.02a | 0.47±0.01a | 0.45±0.03a | 0.46±0.02a | 0.44±0.01a | 0.44±0.02a |

| Serine | 1.96±0.02a | 1.96±0.02a | 2.06±0.02b | 2.07±0.01b | 2.12±0.02b | 2.15±0.02b |

| Threonine | 2.10±0.02a | 2.09±0.02a | 2.27±0.03b | 2.28±0.03b | 2.30±0.03b | 2.30±0.02b |

| Tyrosine | 0.84±0.03a | 0.84±0.02a | 0.99±0.02ab | 0.99±0.01ab | 1.15±0.02c | 1.15±0.02c |

| Valine | 1.44±0.02b | 1.44±0.01a | 1.62±0.02b | 1.65±0.01b | 1.62±0.02b | 1.63±0.01b |

| Values are means of triplicate±SD, Samples carrying the same superscripts in the same row are not significantly different at (p>0.05), | ||||||

| (a) Pycnanthus ostreatus cultivated on wood substrate (Canarium sp.) without fortification, (b) Pycnanthus ostreatus cultivated on wood substrate (Canarium sp.) fortified with iron, (c) Pycnanthus ostreatus cultivated on wood substrate (Ceiba pentandra) without fortification, (d) Pycnanthus ostreatus cultivated on wood substrate (Ceiba pentandra) fortified with iron, (e) P. ostreatus cultivated on wood substrate (Pycnanthus angolensis) without fortification and (f) Pycnanthus ostreatus cultivated on wood substrate (Pycnanthus angolensis) fortified with iron | ||||||

DISCUSSION

The substrate and most especially the nutrient therein used in cultivating Pleurotus ostreatus significantly affect its nutrient composition. Mushrooms are known to possess the unique attribute of absorbing nutrient from the substrates on which they are cultivated and bioaccumulate them as functional compounds with nutraceutical, pharmaceutical and cosmeceutical potentials22. In this study, the vitamins C and A levels of P. ostreatus varies across the different substrates used in its cultivation. Vitamin C content was far higher than vitamin A in all the P. ostreatus. In a previous report, a comprehensive analysis on the nutritional composition of two Pleurotus spp., revealed that vitamin C was the most abundant23. Vitamins are essential for human health, and their levels can be influenced by substrate type and mineral supplementation24.

| Table 2: | Fatty acid content (%) of cultivated P. ostreatus | |||

| Fatty acids | A | B | C | D | E | F |

| Myristic | 0.62±0.03b | 0.67±0.03b | 0.52±0.01a | 0.56±0.03a | 0.60±0.03ab | 0.65±0.04b |

| Pentadecanoic | 0.25±0.0a | 0.29±0.01b | 0.24±0.02a | 0.30±0.02b | 0.25±0.01a | 0.31±0.02b |

| Palmitic | 26.86±0.30b | 28.21±0.23c | 21.83±0.49a | 25.29±0.38b | 29.30±0.37c | 29.29±0.39c |

| Palmitoleic | 0.45±0.04b | 0.64±0.09c | 0.37±0.05a | 0.55±0.03bc | 0.43±0.05a | 0.57±0.04bc |

| Stearic | 26.15±0.89b | 29.41±0.89c | 23.92±0.16a | 26.44±0.62b | 27.37±0.20cd | 28.31±0.35c |

| Oleic | 30.88±0.54d | 33.33±0.75a | 30.24±0.39d | 33.95±0.18a | 29.94±0.17b | 32.33±0.40c |

| Linoleic acid | 0.24±0.02a | 0.31±0.02c | 0.27±0.02b | 0.28±0.04b | 0.27±0.01b | 0.31±0.02c |

| Values are means of triplicate±SD, Samples carrying the same superscripts in the same row are not significantly different at (p>0.05), (a) Pycnanthus ostreatus cultivated on wood substrate (Canarium sp.) without fortification, (b) Pycnanthus ostreatus cultivated on wood substrate (Canarium sp.) fortified with iron, (c) Pycnanthus ostreatus cultivated on wood substrate (Ceiba pentandra) without fortification, (d) Pycnanthus ostreatus cultivated on wood substrate (Ceiba pentandra) fortified with iron, (e) Pycnanthus ostreatus cultivated on wood substrate (Pycnanthus angolensis) without fortification and (f) Pycnanthus ostreatus cultivated on wood substrate (Pycnanthus angolensis) fortified with iron | ||||||

Moreover, studies have demonstrated that iron fortification of substrates can meaningfully alter the nutritional composition of P. ostreatus, enriching its mineral and phytochemical makeup, and enhancing amino acid profiles13,14,25. Amino acid composition is a key nutritional indicator of edible mushrooms such as Pleurotus ostreatus. Past studies revealed that glutamic acid typically dominates the profile, contributing to both nutritional value and umami flavour26,27. However, the implications of mineral fortification, particularly with iron on amino acid composition remain largely unexplored.

In this present study, iron fortification generally increased the level of most amino acids across substrates. Glutamic acid was the most abundant amino acid in all P. ostreatus samples. This is in conformity with previous studies that revealed glutamic acid as the most abundant amino acid in Pleurotus spp28-30.

Amino acids, which are primary products of metabolism, are produced during the growth of mushrooms31. The value of glutamic acid content of iron-fortified P. ostreatus cultivated on P. ongoleubis was the highest and it ranges from 9.07 to 10.70/100 g. This suggest that iron supplementation during the cultivation of mushrooms enhances amino acid accumulation in synergy with certain substrates like Pycnanthus angolensis. This finding correlates with previous studies, which reported glutamic acid as the most abundant amino acid in P. ostreatus, with levels frequently ranging from 7-9/100 g in fruiting bodies cultivated on sawdust, straw, or agricultural wastes26,27. The observed range of 9.07 to 10.70/100 g for glutamic acid is significantly higher, especially in the iron-fortified samples. This shows the potential synergistic effects of the substrate used and the iron fortification during mushroom cultivation. The interaction between these factors appears to enhance the amino acid profile, contributing to improved nutritional quality.

The fatty acid profile of iron and non-iron fortified P. ostreatus revealed notable differences across different substrates and fortification conditions. Essential fatty acids present in P. ostreatus include myristic acid, palmitic acid, palmitoleic acid, stearic acid, oleic acid, pentadecanoic acid, and linoleic acid. Pleurotus ostreatus fortified with iron exhibited higher concentrations of certain fatty acids compared to non-fortified P. ostreatus. The observed variations correlate with previous researches on the influence of substrate and mineral fortification on fungal lipid metabolism32. Studies have highlighted that substrate composition affects fungal lipid biosynthesis due to variations in nutrient availability and metabolic pathways32. Additionally, mineral fortification has been shown to enhance fungal growth and lipid accumulation33. In a previous study, it was observed that more fatty acids, fatty aldehydes, and squalene (18 compounds) were found in selenium fortified Pleurotus ostreatus while 13 compounds were present in non-selenium fortified Pleurotus ostreatus29. Generally metal ions are known to influence lipid production in mushrooms by affecting enzyme activity and metabolic pathways, ultimately leading to changes in the lipid content of fungal34.

Previous researches consistently report palmitic (C16:0), stearic (C18:0), oleic (C18:1), and linoleic (C18:2) acids as dominant components of P. ostreatus lipids35. Oleic and linoleic acids often define the unsaturated fraction, with oleic typically ranging between 25-35% and palmitic around 20-30%. This study correlates with the past studies with iron- fortified P. ostreatus cultivated on Canarium sp and Ceiba pentandra show oleic levels within expected upper limits (≈ 33-34%), and palmitic values (~29%).

CONCLUSION

Conclusively, this study shows that iron fortification of wood substrates used for the cultivation of P. ostreatus significantly affected its vitamins, fatty, and amino acid content. The effect of iron fortification on the vitamins, fatty, and amino acid content of P. ostreatus was more pronounced in Pycnanthus angolensis wood. The iron-enriched P. ostreatus could be used to combat iron deficiency and macronutrient deficiency in human, especially in areas reliant on cereal grains and starchy foods as their main staple food.

SIGNIFICANCE STATEMENT

This study discovered the nutrient-enhancing effect of iron fortification on Pleurotus ostreatus, which can be beneficial for improving dietary iron, vitamins, amino acids, and fatty acids in nutritionally vulnerable populations. By demonstrating that iron-enriched tropical wood substrates, particularly Pycnanthus angolensis, significantly elevate essential nutrients such as vitamins A and C, glutamic acid, leucine, and key fatty acids, the study highlights the potential of fortified mushrooms as an affordable functional food. These findings also provide new insight into using substrate modification to biofortify edible fungi for public health nutrition. Moreover, this study will help researchers uncover the critical areas of mushroom-based biofortification that many researchers were not able to explore. Thus, a new theory on nutrient-optimized fungal cultivation may be arrived at.

REFERENCES

- Słyszyk, K., M. Siwulski, A. Wiater, M. Tomczyk and A. Waśko, 2024. Biofortification of mushrooms: A promising approach. Molecules, 29.

- Siwulski, M., Z. Magdziak, P. Niedzielski, M. Gąsecka and A. Budka et al., 2025. Wild-grown, tissue-cultured, and market Pleurotus ostreatus: Implications for chemical characteristics. J. Food Compos. Anal., 147.

- Galani, Y.J.H., C. Orfila and Y.Y. Gong, 2022. A review of micronutrient deficiencies and ana lysis of maize contribution to nutrient requirements of women and children in Eastern and Southern Africa. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr., 62: 1568-1591.

- Kalač, P., 2016. Proximate Composition and Nutrients. In: Edible Mushrooms: Chemical Composition and Nutritional Value, Kalač, P. (Ed.), Elsevier, Amsterdam, Netherlands, ISBN: 978-0-12-804455-1, pp: 7-69.

- Oyetayo, V.O., 2023. Mineral element enrichment of mushrooms for the production of more effective functional foods. Asian J. Biol. Sci., 16: 18-29.

- Fadugba, A.E., V.O. Oyetayo, B.I. Osho and O.O. Olaniyi, 2024. Assessment of the effect of iron and selenium fortification on the amino acids profile of Pleurotus ostreatus. Vegetos, 37: 494-499.

- Kalač, P., 2013. A review of chemical composition and nutritional value of wild-growing and cultivated mushrooms. J. Sci. Food Agric., 93: 209-218.

- Bilal, A.W., R.H. Bodha and A.H. Wani, 2010. Nutritional and medicinal importance of mushrooms. J. Med. Plants Res., 4: 2598-2604.

- Raman, J., K.Y. Jang, Y.L. Oh, M. Oh, J.H. Im, H. Lakshmanan and V. Sabaratnam, 2021. Cultivation and nutritional value of prominent Pleurotus spp.: An overview. Mycobiology, 49: 1-14.

- Elkanah, F.A., M.A. Oke and E.A. Adebayo, 2022. Substrate composition effect on the nutritional quality of Pleurotus ostreatus (MK751847) fruiting body. Heliyon, 8.

- Oyetayo, V.O. and F.L. Oyetayo, 2025. Health promoting effects of bioactive compounds in mushrooms. Trends Biol. Sci., 1: 3-11.

- Wang, M. and R. Zhao, 2023. A review on nutritional advantages of edible mushrooms and its industrialization development situation in protein meat analogues. J. Future Foods, 3: 1-7.

- Oyetayo, V.O., 2024. Fortification with selenium markedly affects biological efficiency and the distribution of essential and non-essential amino acids in Pleurotus ostreatus. Eurasian J. Food Sci. Technol., 8: 43-51.

- Ariyo, O.O., V.O. Oyetayo and D.V. Adegunloye, 2024. Effect of zinc and iron fortification on the antioxidant property of Pleurotus ostreatus grown on different tropical wood substrates. FUTA J. Life Sci., 4: 10-17.

- Achikanu, C.E., P.E. Eze-Steven, C.M. Ude and O.C. Ugwuokolie, 2013. Determination of the vitamin and mineral composition of common leafy vegetables in South Eastern Nigeria. Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. Appl. Sci., 2: 347-353.

- Barros, L., T. Cruz, P. Baptista, L.M. Estevinho and I.C.F.R. Ferreira, 2008. Wild and commercial mushrooms as source of nutrients and nutraceuticals. J. Food Chem. Toxicol., 46: 2742-2747.

- Nirmalkar, D. and V. Naidu, 2025. Thiamine and riboflavin in pleurotusostreatus mushrooms assaying using a simplified, specific HPLC method in different substrate. Scope, 15: 381-391.

- Huang, B.F., X.D. Pan, J.S. Zhang, J.J. Xu and Z.X. Cai, 2020. Determination of vitamins D2 and D3 in edible fungus by reversed-phase two-dimensional liquid chromatography. J. Food Qual., 2020.

- AOAC, 2019. Official Methods of Analysis of AOAC International. 21st Edn., Association of Official Analytical Chemists, Washington, DC, USA, ISBN: 978-0935584899.

- Fernandes, I. and R. Pinto, 2019. Fatty acids polyunsaturated as bioactive compounds of microalgae: Contribution to human health. Global J. Nutr. Food Sci., 2.

- Horwitz, W. and G.W. Latimer, 2006. Official Methods of Analysis of AOAC International. 18th Edn., AOAC International, Gaithersburg, Maryland, ISBN: 9780935584776.

- Ogidi, C.O., V.O. Oyetayo and B.J. Akinyele, 2020. Wild Medicinal Mushrooms: Potential Applications in Phytomedicine and Functional Foods. In: An Introduction to Mushroom. Passari, A.K. and S. Sánchez (Eds.), IntechOpen, London, United Kingdom, ISBN: 978-1-78985-955-3, pp: 118-126.

- Singh, A., R.K. Saini, A. Kumar, P. Chawla and R. Kaushik, 2025. Mushrooms as nutritional powerhouses: A review of their bioactive compounds, health benefits, and value-added products. Foods, 14.

- Tanumihardjo, S.A., R.M. Russell, C.B. Stephensen, B.M. Gannon and N.E. Craft et al., 2016. Biomarkers of nutrition for development (BOND)-vitamin A review. J. Nutr., 146: 1816S-1848S.

- Scheid, D.L., R.F. da Silva, V.R. da Silva, C.O. da Ros, M.A.B. Pinto, M. Gabriel and M.R. Cherubin, 2020. Changes in soil chemical and physical properties in pasture fertilised with liquid swine manure. Soils Plant Nutr., 77.

- Kayode, R.M.O., T.F. Olakulehin, B.S. Adedeji, O. Ahmed, T.H. Aliyu and A.H.A. Badmos, 2015. Evaluation of amino acid and fatty acid profiles of commercially cultivated oyster mushroom (Pleurotus sajor-caju) grown on gmelina wood waste. Niger. Food J., 33: 18-21.

- Tagkouli, D., A. Kaliora, G. Bekiaris, G. Koutrotsios, M. Christea, G.I. Zervakis and N. Kalogeropoulos, 2020. Free amino acids in three Pleurotus species cultivated on agricultural and agro-industrial by-products. Molecules, 25.

- Oyetayo, F.L., A.A. Akindahunsi and V.O. Oyetayo, 2007. Chemical profile and amino acids composition of edible mushrooms Pleurotus sajor-caju. Nutr. Health, 18: 383-389.

- Oyetayo, V.O., A.E. Fadugba and O.O. Ariyo, 2024. Effects of selenium fortification on the mineral and fatty acid properties of Pleurotus ostreatus jacq. Acta Sci. Nutr. Health, 8: 24-28.

- Fasoranti, O.F., C.O. Ogidi and V.O. Oyetayo, 2019. Nutrient contents and antioxidant properties of Pleurotus spp. cultivated on substrate fortified with selenium. Curr. Res. Environ. Appl. Mycol., 9: 66-76.

- Yang, Q., D. Zhao and Q. Liu, 2020. Connections between amino acid metabolisms in plants: Lysine as an example. Front. Plant Sci., 11.

- Sánchez, C., 2010. Cultivation of Pleurotus ostreatus and other edible mushrooms. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol., 85: 1321-1337.

- Huang, X., H. Luo, T. Mu, Y. Shen, M. Yuan and J. Liu, 2018. Enhancement of lipid accumulation by oleaginous yeast through phosphorus limitation under high content of ammonia. Bioresour. Technol., 262: 9-14.

- Melanouri, E.M., I. Diamantis, M. Dedousi, E. Dalaka and P. Antonopoulou et al., 2025. Pleurotus ostreatus: Nutritional enhancement and antioxidant activity improvement through cultivation on spent mushroom substrate and roots of leafy vegetables. Fermentation, 11.

- Šebesta, M., H. Vojtková, V. Cyprichová, A.P. Ingle, M. Urík and M. Kolenčík, 2022. Mycosynthesis of metal-containing nanoparticles-fungal metal resistance and mechanisms of synthesis. Int. J. Mol. Sci., 23.

How to Cite this paper?

APA-7 Style

Oyetayo,

V.O., Ariyo,

O.O. (2026). Comparative Analysis of Vitamin, Amino Acid, and Fatty Acid Profiles in Pleurotus ostreatus Cultivated on Iron-Fortified Wood Substrates. Trends in Biological Sciences, 2(1), 33-41. https://doi.org/10.21124/tbs.2026.33.41

ACS Style

Oyetayo,

V.O.; Ariyo,

O.O. Comparative Analysis of Vitamin, Amino Acid, and Fatty Acid Profiles in Pleurotus ostreatus Cultivated on Iron-Fortified Wood Substrates. Trends Biol. Sci 2026, 2, 33-41. https://doi.org/10.21124/tbs.2026.33.41

AMA Style

Oyetayo

VO, Ariyo

OO. Comparative Analysis of Vitamin, Amino Acid, and Fatty Acid Profiles in Pleurotus ostreatus Cultivated on Iron-Fortified Wood Substrates. Trends in Biological Sciences. 2026; 2(1): 33-41. https://doi.org/10.21124/tbs.2026.33.41

Chicago/Turabian Style

Oyetayo, Victor, Olusegun, and Olatomiwa Olubunmi Ariyo.

2026. "Comparative Analysis of Vitamin, Amino Acid, and Fatty Acid Profiles in Pleurotus ostreatus Cultivated on Iron-Fortified Wood Substrates" Trends in Biological Sciences 2, no. 1: 33-41. https://doi.org/10.21124/tbs.2026.33.41

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.