Preliminary Oncopharmacological Evaluation of Praxelis clematidea (Griseb): Growth Inhibition, Cytotoxicity, and Antioxidant Activities

| Received 30 Sep, 2025 |

Accepted 11 Dec, 2025 |

Published 31 Dec, 2025 |

Background and Objective: Praxelis clematidea (Griseb), an Asteraceae species often classified as an invasive weed, has recently gained research attention for its pharmacological potential. However, its oncopharmacological properties remain unexplored. This study aimed to evaluate the growth inhibitory, cytotoxic, and antioxidant activities of P. clematidea extracts and fractions to provide preliminary insights into its possible anticancer potential. Materials and Methods: Crude extract of P. clematidea was obtained using Soxhlet extraction (yield: 12.7%) and partitioned into chloroform (26%) and aqueous (61.6%) fractions. Growth inhibition was assessed on Sorghum bicolor radicles over 96 hrs, cytotoxicity on Raniceps ranninus tadpoles for 24 hrs, and antioxidant activity using the ABTS radical scavenging assay. Results were statistically analyzed, and dose response relationships were evaluated. Results: Radicle growth inhibition was both dose- and time-dependent, with nearly complete suppression at 30 mg/mL after 96 hrs. Radicle lengths were significantly reduced: Crude (0.2±0.0 cm), aqueous (0.767±0.067 cm), and chloroform (0.167±0.067 cm) compared with the control (10.667±0.318 cm). Cytotoxicity increased with concentration, with the crude and chloroform fractions causing 100% mortality at 20 mg/mL within three and 2 hrs, respectively, while the aqueous fraction showed only 13.33% mortality after 24 hrs. Antioxidant activity was strongest in the crude extract (82.52% inhibition; EC50 = 150.04 μg/mL) and chloroform fraction (78.8%; EC50 = 207.7 μg/mL), but weak in the aqueous fraction (11.48%; EC50 = 2000 μg/mL). Conclusion: The findings suggest that P. clematidea contains moderately non-polar bioactive compounds responsible for its inhibitory, cytotoxic, and antioxidant effects. These preliminary results indicate promising oncopharmacological potential, supporting further isolation, structural characterization, and mechanistic studies of its active constituents.

| Copyright © 2025 Owolabi and Ayinde. This is an open-access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. |

INTRODUCTION

Cancer remains one of the most serious health issues of our time, responsible for nearly one in every six deaths globally1. While conventional chemotherapy has helped save countless lives, it often comes with harsh side effects, growing resistance, and high treatment costs, challenges that are especially difficult for patients in low and middle-income countries to overcome2. These concerns have driven scientists to look beyond synthetic drugs and explore natural alternatives, particularly medicinal plants, as potential sources for safer and more affordable cancer treatments3,4.

Nature has long been a trusted ally in the fight against cancer. Many of the anticancer drugs we use today are either derived from or inspired by natural products5. Plant-derived compounds like flavonoids, alkaloids, and terpenoids are well known for their ability to stop the growth of cancer cells or even trigger their death6,7. One plant that’s starting to catch researchers’ attention is P. clematidea (Griseb.), a fast spreading member of the Asteraceae family. Originally native to South America, this invasive plant has now made its way into many parts of Africa and Asia8,9.

Though often viewed as a weed due to its aggressive spread, P. clematidea may hold surprising medicinal value. Recent studies have shown it’s packed with phytochemicals like flavonoids, alkaloids, and essential oil compounds that are known to possess antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory9-11. Yet, despite this promising chemical profile, there’s no research, as far as we know on how this plant might help in cancer treatment. Although Intanon et al.9 reported antioxidant activity of the plant, they only reported the DPPH assay. More evidence is needed, especially through simple and reliable tests that can give us a clearer idea of its potential.

Oxidative stress plays a critical role in the initiation and progression of cancer, as well as in other chronic diseases12. Antioxidants, whether endogenous or plant-derived, help counteract free radical damage, thereby modulating pathways linked to cell survival, apoptosis, and carcinogenesis13,14.

Coupled with the cost implications of anti-cancer synthetic drugs2, methods of screening is even more challenging in terms of cost and facilities15. To address this, scientists often begin with straightforward but informative screening tools. The root growth inhibition test using S. bicolor (guinea corn), for instance, is a sensitive method for spotting substances that interfere with cell division4,16. Similarly, the use of tadpoles, such as R. ranninus, in cytotoxicity tests offers a practical and ethical way to evaluate how toxic or bioactive a plant extract might be17. Together, these models provide an accessible first step in exploring anticancer potential.

This study, aim to take that first step by conducting a preliminary oncopharmacological evaluation of P. clematidea using guinea corn radicle inhibition and tadpole cytotoxicity assays, as well as ABTS anti-oxidant assessment, to investigate whether this plant’s extracts show early signs of anti-cancer activity, and if so, to further fractionate the extract into chloroform and aqueous fractions to determine the polarity nature of the constituents responsible for the activities. Findings could open new doors not only for cancer research but also for turning an invasive species into a useful natural resource, contributing to the growing field of sustainable drug discovery.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Collection and preparation of plant material: The fresh whole plant of P. clematidea was obtained from the University of Benin, Ugbowo Campus, Egor, LGA, Edo State, Nigeria, in June, 2023, identified and authenticated at the Pharmacognosy Department of Dora Akunyili College of Pharmacy, Igbinedion University, Okada, Edo State, Nigeria, and voucher specimen deposited in the herbarium with herbarium number IUO/23/356.

The plant samples were sorted, rinsed, and air-dried at room temperature for 7 days and transferred into an oven maintained at 40°C for an additional 4 hrs before pulverization into powder form using an electrical miller (Chris Norris, England). The powdered plant material (1.8 kg) was subjected to Soxhlet extraction using methanol. The menstrum obtained was concentrated in vacuo with a rotary evaporator (RES52-1; SearchTech Instruments) to get a dark green semi-solid paste, which was then weighed and stored refrigerator until further use.

Evaluation of the growth inhibitory effect of crude on the guinea corn (S. bicolor) radicle length: Untreated guinea corn seeds were purchased from the Okada community market, Edo State. The viable seeds were sterilized with absolute ethanol, rinsed with water, and dried before use. Ten milliliters of different concentrations (1, 2, 5, 10, 20, and 30 mg/mL) of the extracts were poured into 9 cm wide Petri dishes underlaid with cotton and filter paper. Twenty viable seeds were spread on each plate and incubated in the dark. The length (cm) of the radicles emerging from the seeds were measured at 24, 48, 72, and 96 hrs. The control seeds were treated with 10 mL of water containing no extract16. All experiments were triplicated.

Evaluation of the cytotoxic effect of the crude extract on tadpoles (R. ranninus): All animal (Raniceps ranninus) experimental procedures were conducted in strict adherence to the approved Ethical Committee on Animal Handling Guidelines of the Research and Ethical Review Committee, Igbinedion University, Okada (approval number: IUO/Ethics/067/25), which aligns with the International Guidelines for Care and use of Vertebrate Animals in Research.

The cytotoxicity experiment was done according to the procedures4,16 with slight modifications. Briefly, R. ranninus eggs were collected from a still pond in the Okada Town community, and the eggs were nurtured and hatched in a big bowl containing water from the egg source. A 10-day-old viable Tadpoles of equal size were selected for the experiment.

Ten viable tadpoles were selected with the aid of a broken Pasteur pipette and introduced into small-sized beakers with 30 mL of the water from the pond where the tadpoles were hatched. The 19 mL of distilled water was added to 1 mL of the different extract concentrations of 1, 2, 5, 10, and 20 mg/mL. The final volume being 50 mL, each of these concentrations were triplicated, while the controls were treated with distilled water. The duration and mortality rates were noted and recorded. Total submergence of the tadpoles was used to indicate mortality.

Antioxidant activity: The antioxidant potential of the extracts was evaluated using the 2, 2'-Azinobis-3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid (ABTS) radical decolorization assay18. Briefly, freshly prepared (6-8 hrs) ABTS· stock solution was diluted with phosphate-buffered saline 5 mM (pH 7.4) to an absorbance of 0.70 at 734 nm. Then, 1.0 mL of this diluted ABTS· was added to 20 μL of varying concentrations (50, 100, 200, and 400 μg/mL) of the sample, and the absorbance was taken 5 min after the initial mixing. Ascorbic acid (0.5 μg/mL) was used as a standard antioxidant, while ABST solution was used as a control; all the experiments were conducted in triplicate. The activity was expressed as percent ABTS· scavenging calculated as follows:

Partitioning of the methanol crude extract: Crude methanol extract (120 g) was reconstituted in a small amount of methanol, diluted with water and then partitioned with chloroform using a separatory funnel of 2000 mL capacity. Chloroform and aqueous fractions were separately collected. This procedure was repeated till a transparent chloroform layer was observed. The two fractions (chloroform and aqueous) were concentrated using a water bath, and their respective yields were noted.

Growth inhibitory, cytotoxicity, and anti-oxidant activities of the chloroform and aqueous fractions: The effects of the two fractions of the extract were separately evaluated for growth inhibition, cytotoxicity, and antioxidant activities at the same concentrations and procedures as stated above.

Statistical analysis: All experiments were conducted in triplicate and repeated at least twice, and the results are expressed as Mean±Standard Deviation. Statistical analysis was performed using analysis of variance (ANOVA) (SigmaPlot version 15.0). Differences were considered statistically significant at p<0.01 and p<0.05.

RESULTS

Yields of the plant extract: After extraction through Soxhlet extraction of 1.8 kg of the powdered P. clematidea, a crude extract yield of 229 g was obtained, corresponding to 12.7% of the starting plant powdered sample. The crude extract (120 g) partitioned between chloroform and water yielded chloroform fraction (31.2 g, i.e, 26%) and aqueous fraction (73.9 g, i.e, 61.6%).

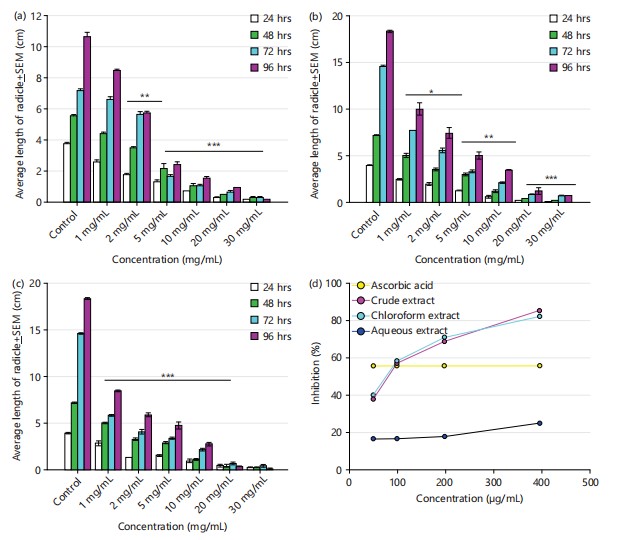

Results of growth inhibitory effects of crude extract on S. bicolor radicle length growth: The growth inhibitory effect of P. clematidea crude extract on radicle length growth of S. bicolor seeds was assessed over 96 hrs. The results demonstrated a concentration- and time-dependent inhibition of radicle elongation compared to the untreated control group. At 24 hrs, the mean radicle length of the control seeds was 3.770±0.067 cm. A progressive reduction in radicle growth was observed with increasing extract concentrations: 2.567±0.145 cm (1 mg/mL), 1.767±0.088 cm (2 mg/mL), 1.300±0.115 cm (5 mg/mL), 0.700±0.000 cm (10 mg/mL), 0.267±0.033 cm (20 mg/mL), and 0.167±0.033 cm (30 mg/mL).

By 48 hrs, the control seeds reached a radicle length of 5.567±0.088 cm, while treated groups exhibited significantly reduced lengths: 4.400±0.115 cm (1 mg/mL), 3.500±0.057 cm (2 mg/mL), 2.167±0.318 cm (5 mg/mL), 1.067±0.133 cm (10 mg/mL), 0.500±0.000 cm (20 mg/mL), and 0.267±0.033 cm (30 mg/mL). At 72 hrs, the control group exhibited continued growth with a radicle length of 7.200±0.115 cm, whereas increasing concentrations of the extract continued to inhibit growth: 6.600±0.208 cm (1 mg), 5.667±0.176 cm (2 mg), 1.667±0.088 cm (5 mg), 1.033±0.088 cm (10 mg), 0.667±0.067 cm (20 mg), and 0.267±0.033 cm (30 mg).

At the final time point (96 hrs), control seeds had a mean radicle length of 10.667±0.318 cm, while seeds treated with P. clematidea extract showed marked inhibition in a dose-dependent fashion: 8.500±0.058 cm (1 mg), 5.767±0.088 cm (2 mg), 2.433±0.167 cm (5 mg), 1.533±0.120 cm (10 mg), 0.933±0.033 cm (20 mg), and 0.200±0.000 cm (30 mg). The entire results are presented in (Fig. 1a).

Results of growth inhibitory effects of chloroform and aqueous fractions on radicle length: The aqueous fraction of P. clematidea demonstrated a concentration and time-dependent inhibitory effect on the radicle growth of S. bicolor over the 96-hrs experimental period (Fig. 1b). In the control group, radicle length increased progressively from 3.967±0.067 cm at 24 hrs to 18.333±0.120 cm at 96 hrs. In contrast, treatment with increasing concentrations of the aqueous fraction resulted in though weak suppression of radicle elongation.

At 1 mg/mL, radicle lengths were reduced to 2.467±0.067, 5.033±0.240, 7.700±0.000 cm, and 10.000±0.656 cm at 24, 48, 72, and 96 hrs, respectively. More pronounced inhibition was observed at 5 mg/mL, with radicle lengths measuring 1.233±0.088 cm (24 hrs) and reaching only 5.033±0.384 cm by 96 hrs.

High concentrations (10-30 mg/mL) exhibited strong suppression, with 30 mg/mL producing near-complete growth inhibition, where radicle lengths were 0.133±0.033 cm at 24 hrs and only 0.767±0.067 cm at 96 hrs. The highest level of inhibition was thus recorded at 30 mg/mL across all time points, suggesting potent phytotoxic effects of the aqueous fraction on S. bicolor radicle elongation (Fig. 1b).

|

However, the chloroform faction was noticed to suppress the growth of the radicle significantly (p<0.05) with increase in concentrations more effectively than the aqueous fraction. The 1 mg/mL resulted in reduced radicle lengths of 2.867±0.240, 5.033±0.067, 5.833±0.088, and 8.467±0.088 cm at 24, 48, 72, and 96 hrs, respectively. At 5 mg/mL, radicle elongation was further suppressed, reaching only 4.767±0.393 cm at 96 hrs.

The highest concentrations (20-30 mg/mL) produced strong inhibitory effects throughout the experiment. At 30 mg/mL, radicle length was restricted to 0.233±0.033 cm at 24 hrs and 0.167±0.067 cm at 96 hrs, indicating near-complete growth arrest. Notably, 20 mg/mL treatment showed a slight decrease in radicle length between 72 hrs (0.700±0.153 cm) and 96 hrs (0.367±0.067 cm), suggesting possible tissue necrosis at higher exposure durations (Fig. 1c).

Result of cytotoxicity effects of the crude extract, aqueous and chloroform fractions on tadpoles: The fractions of P. clematidea exhibited a clear concentration and time dependent cytotoxic effect on R. ranninus tadpoles, as indicated by increasing percentage mortality over the 24 hrs exposure period (Table 1-3). No mortality was recorded in the control group throughout the experiment.

| Table 1: | Mortality effects of the crude extract on tadpoles (%) | |||

| (mg/mL) | 2 hrs | 3 hrs | 4 hrs | 5 hrs | 6 hrs | 7 hrs | 8 hrs |

| Control | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 1 | - | - | 3.33±0.333 | 10±0.577 | 33.33±0.667 | 73.33±0.667 | 100±0 |

| 2 | - | 3.33±0.333 | 23.33±0.333 | 43.33±0.333 | 66.67±0.667 | 100±0 | - |

| 5 | 6.67±0.333 | 23.33±0.333 | 40±0 | 46.67±0.333 | 100±0 | - | - |

| 10 | - | 43.33±0.333 | 76.67±0.333 | 100±0 | - | - | - |

| 20 | 86.67±0.333 | 100±0 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Table 2: | Mortality effects of the aqueous fraction on tadpoles (%) | |||

| (mg/mL) | 2 hrs | 6 hrs | 8 hrs | 10 hrs | 12 hrs | 24 hrs |

| Control | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 1 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 2 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 5 | - | - | 6.67±0.667 | - | 10±1 | |

| 10 | - | 0.33±0.333 | - | 6.67±0.667 | - | 10±1 |

| 20 | - | - | - | - | - | 13.33±1.333 |

| Table 3: | Mortality effects of the chloroform fraction on tadpoles (%) | |||

| (mg/mL) | 1 hr | 2 hrs | 3 hrs | 4 hrs | 5 hrs | 6 hrs | 7 hrs | 8 hrs | 12 hrs | 24 hrs |

| Control | 0±0 | 0±0 | 0±0 | 0±0 | 0±0 | 0±0 | 0±0 | 0±0 | 0±0 | 0±0 |

| 1 | 0±0 | 0±0 | 0±0 | 0±0 | 16.67±0.33 | 53.33±0.67 | 100±0 | - | - | - |

| 2 | 0±0 | 0±0 | 26.7±0.33 | 73.3±0.33 | 100±0 | - | - | - | - | - |

| 5 | 0±0 | 0±0 | 53.3±1.76 | 100±0 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 10 | 0±0 | 23.3±0.67 | 100±0 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 20 | 63.33±0.33 | 100±0 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Values are Mean±SEM, n = 10, -means no mortality | ||||||||||

The crude extract, at the lowest concentration (1 mg/mL), mortality began at 4 hrs (3.33±0.333%) and increased progressively to 33.33±0.667% by 6 hrs, and 100±0% by the 8 hrs. At 2 mg/mL, mortality was first observed at 3 hrs (3.33±0.333%) and reached 100±0% by 7 hrs. At 5 mg/mL, mortality reached 23.33±0.333% by 3 hrs and achieved 100% mortality by the 6 hrs. At 10 mg/mL, 43.33±0.333% mortality was observed at 3 hrs, and reached 100% mortality within 5 hrs. The most lethal effect was recorded at 20 mg/mL, where 86.67±0.333% mortality was recorded within 2 hrs and complete mortality occurred by 3 hrs (Table 1).

The aqueous fraction of P. clematidea induced minimal mortality in R. ranninus tadpoles within the 24 hrs exposure period, with effects appearing only at higher concentrations and longer durations (Table 2). No mortality was recorded in the control group or at 1 mg/mL and 2 mg/mL across all time points. At 5 mg/mL, mortality was first observed at 12 hrs (6.67±0.667%) and reached 10±1% by 24 hrs. A similar pattern was observed at 10 mg/mL, where mortality began earlier (6 hrs: 0.333±0.333%) and increased to 6.67±0.667% at 12 hrs, eventually reaching 10±1% by 24 hrs. The highest tested concentration (20 mg/mL) resulted in the most pronounced effect, with mortality of 13.33±1.333% recorded at 24 hrs, indicating a weak cytotoxic effect (Table 2).

The chloroform fraction, at the lowest concentration (1 mg/mL), mortality began at 5 hrs (16.67±0.333%) and increased progressively to 100±0% by the 7 hrs. At 2 mg/mL, mortality was first observed at 3 hrs (26.67±0.333%) and reached 100±0% by 5 hrs. Higher concentrations induced more rapid lethality. At 5 mg/mL, mortality reached 53.33±1.764% by 3 hrs and achieved 100% mortality (10±0%) by the 4 hrs. At 10 mg/mL, 100% mortality occurred within 3 hrs, following an initial 23.33±0.667% at 2 hrs. The most potent effect was observed at 20 mg/mL, where 63.33±0.333% mortality was recorded within 1 hr and complete mortality occurred by 2 hrs (Table 3).

| Table 4: | Percentage inhibition and EC50 of P. clematidae crude extract | |||

| Crude extract | Chloroform fraction | Aqueous fraction | |||||

| Ascorbic acid AA (0.5 μg/mL) |

Concentration (μg/mL) |

Inhibition (%) | EC50 μg/mL | Inhibition (%) | EC50 μg/mL | Inhibition (%) | EC50 μg/mL |

| 45.711±3.062 | 50 | 26.757±1.710 | 150.04 | 29.29±0.013 | 207.7 | 1.552±0.004 | 2000 |

| 45.711±3.062 | 100 | 49.306±0.572 | 50.531±0.004 | 1.838±0.004 | |||

| 45.711±3.062 | 200 | 62.95±0.82 | 65.605±0.018 | 3.064±0.007 | |||

| 45.711±3.062 | 400 | 82.516±3.625 | 78.799±0.023 | 11.479±0.019 | |||

| AA = Ascorbic acid, PC = P. clematidae. Each value is expressed as Mean±SEM (n = 3) and EC50 (μg/mL): Effective concentration at which 50% Inhibition was attained | |||||||

Results of ABTS radical scavenging assay of the crude extract, aqueous and chloroform fractions: The antioxidant potential of P. clematidea extract was evaluated using the ABTS radical scavenging assay, and the results were expressed as percentage inhibition (Table 4) and EC50 calculated from the plots of (%) inhibition against the concentrations. Ascorbic acid, used as a standard antioxidant, exhibited a significantly high inhibition value of 45.711±3.062 mg/mL at 0.5 μg/mL concentration, indicating high radical scavenging efficacy. In comparison, P. clematidea crude extract exhibited a concentration-dependent increase in inhibition, ranging from 26.76±1.71% at 50 μg/mL to 82.52±3.63% at 400 μg/mL, with an EC50 value of 150.04 μg/mL. The chloroform fraction demonstrated comparable activity, with inhibition values increasing from 29.29±0.01% at 50 μg/mL to 78.80±0.02% at 400 μg/mL, corresponding to an EC50 of 207.7 μg/mL. In contrast, the aqueous fraction displayed markedly lower activity, with percentage inhibition not exceeding 11.48±0.02% even at the highest concentration tested (Fig. 1d), and a substantially higher EC50 of 2000 μg/mL.

DISCUSSION

This study provides compelling evidence that P. clematidea, a plant often dismissed as an invasive species, harbors potent bioactivities of pharmacological interest. Through a combination of radicle growth inhibition, tadpole cytotoxicity, and antioxidant activity assays, the extract displayed consistent time and concentration-dependent biological effects, supporting its potential as a source of antiproliferative and antioxidant agents. The Soxhlet extraction of 1.8 kg powdered P. clematidea yielded 229 g of crude extract, representing a 12.7% yield, indicative of substantial phytochemical content. Such yield is comparable to other Asteraceae species, reflecting efficient solvent penetration and metabolite solubilization19. High extraction yields are often associated with abundant secondary metabolites like flavonoids and terpenoids, relevant to bioactivity20. This supports the suitability of Soxhlet extraction for maximizing recovery in pharmacognostic investigations21,22.

The significant inhibition of S. bicolor radicle elongation over 96 hrs highlights the presence of bioactive compounds capable of disrupting early cell line development. Particularly at concentrations ≥10 mg/mL, the crude extract caused significant suppression of growth, resulting in near complete growth inhibition (0.2±0.0) at 30 mg/mL, similar trend was observed in the chloroform and aqueous fractions (0.167±0.067, and 0.767±0.067) compared to the control group (10.667±0.318 cm). This inhibitory trend suggests interference with fundamental cellular mechanisms such as mitotic division, elongation, or differentiation, key targets in anticancer strategies23. Comparable phytotoxic effects have been documented in this plant24 and other Astereceae species like Chromolaena odorata, and many are rich in phenolics and sesquiterpene lactones25,26. Given the similarity in patterns, P. clematidea likely exerts cytostatic effects27 that warrant deeper investigation into its antiproliferative potential.

Further supporting this potential is the extract’s cytotoxicity in R. ranninus, which showed rapid mortality in a dose-dependent manner. At 20 mg/mL, complete lethality was recorded within three hours for the crude extract, achieving same at two hours for the chloroform fraction while aqueous fraction only exerted 13% mortality at 24 hrs. Even at the lowest concentration (1 mg/mL), the chloroform fraction resulted in

100% mortality by the 7 hrs. These results mirror cytotoxic profiles commonly observed in preliminary screens for anticancer agents28,29 and suggest possible mechanisms involving membrane integrity disruption, mitochondrial dysfunction30, or oxidative stress induction31,32. The early onset of toxicity and steep mortality gradient reflect a potent and fast-acting mechanism33, further indicating the presence of pharmacologically relevant metabolites20.

From an oncopharmacological standpoint, aquatic bioassays such as this provide a valuable and ethically sound preliminary screening method for cytotoxic agents before more targeted in vitro or in vivo testing34,35. The consistency between the radicle inhibition and tadpole lethality further reinforces the likelihood of antiproliferative activity of the plant under investigation, potentially via shared pathways involving cell cycle arrest or apoptosis36.

In addition to its cytotoxic properties, P. clematidea demonstrated moderate but significant antioxidant capacity in the ABTS radical scavenging assay. The assay revealed that the crude extract of P. clematidea displayed strong, concentration-dependent antioxidant activity, with percent inhibition increasing from 26.76±1.71% at 50 μg/mL to 82.52±3.63% at 400 μg/mL, resulting in an EC50 of 150.04 μg/mL. This contrasts with ascorbic acid used as the positive control which achieved 45.71±3.06% inhibition at 0.5 μg/mL, reflecting its known high efficacy as a radical scavenger37. The significantly lower EC50 of ascorbic acid compared to the plant extract underscores its superior potency38.

The chloroform fraction paralleled the crude extract in antioxidant performance, showing inhibition values rising from 29.29±0.01% at 50 μg/mL to 78.80±0.02% at 400 μg/mL, and an EC50 of 207.7 μg/mL. This indicates that moderately non-polar constituents contribute meaningfully to the antioxidant activity, though their potency is somewhat diminished relative to the full crude extract. Such a decline upon fractionation is consistent with observations in other botanical studies, wherein disruption of synergistic phytochemical interactions can reduce efficacy39. In contrast, the aqueous fraction exhibited feeble radical scavenging capability, with percent inhibition not exceeding 11.48±0.02% even at the highest tested concentration, and an EC50 as high as 2000 μg/mL. This suggests that the principal antioxidant components of P. clematidea are localized in non-polar.

Generally, fractionation, a purification process that groups similar constituents, has been associated with improved efficacy40. In this study, fractionation enhanced the efficacy observed with the crude methanol extract, with sub-fractions showing significantly higher inhibition rates than the initial extract, although this potency was lower than that of ascorbic acid (0.5 μg/mL), the activity level aligns with known medicinal members of the Asteraceae family, such as Chromolaena odorata, Taraxacum officinale, and Cichorium intybus41-43. Generally, all plants have some sort of antioxidant activity, but only the EC50 values indicate the true potential of plant extracts as antioxidants. The lower the EC50 value stronger the antioxidant potential. The EC50 of 150.04 μg/mL was obtained in this current study, normally EC50 value less than 250 μg/mL is regarded as considerable antioxidant44. The antioxidant potential is likely attributed to the plant’s flavonoids, which are known to neutralize free radicals and modulate oxidative stress, a key factor in the pathogenesis of cancer and other chronic diseases45,46.

Further studies, including bioassay guided compound isolation and characterization, are needed to elucidate the chemical nature of these inhibitory compounds and assess their potential application on cancer cell lines.

CONCLUSION

These findings demonstrate that Praxelis clematidea possesses bioactive, moderately non-polar compounds that contribute to its growth-inhibitory, cytotoxic, and antioxidant effects. The plant, once regarded merely as an invasive weed, shows emerging potential as a source of anticancer and antioxidant agents. Its dual significance in ecological management and drug discovery highlights the need for further phytochemical isolation and mechanistic validation to confirm its therapeutic relevance.

SIGNIFICANCE STATEMENT

This study discovered the potent bioactive constituents of Praxelis clematidea that can be beneficial for developing novel anticancer therapeutics. The plant, long considered an invasive weed, demonstrated significant growth-inhibitory, cytotoxic, and antioxidant activities, revealing its overlooked medicinal potential. By establishing the first scientific evidence of its oncopharmacological relevance, the study highlights P. clematidea as a promising candidate for future phytochemical screening, biological validation, and drug-development research. Moreover, this study will help researchers uncover the critical areas of plant-based anticancer drug discovery that many investigators were not able to explore. Thus, a new theory on the therapeutic importance of neglected invasive species may be arrived at.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

To the entire staff of the department of Dharmacognosy in the Faculty of Pharmacy, University of Benin, Edo State, Prof. Dora Akuyili College of Pharmacy, Igbinedion University, Okada, Edo State, Nigeria.

REFERENCES

- Siegel, R.L., T.B. Kratzer, A.N. Giaquinto, H. Sung and A. Jemal, 2025. Cancer statistics, 2025. CA: Cancer J. Clinicians, 75: 10-45.

- Mattila, P.O., R. Ahmad, S.S. Hasan and Z.U.D. Babar, 2021. Availability, affordability, access, and pricing of anti-cancer medicines in low- and middle-income countries: A systematic review of literature. Front. Public Health, 9.

- Fongang, H., A.T. Mbaveng and V. Kuete, 2024. Cancer, Global Burden, and Drug Resistance. In: Advances in Botanical Research, Kuete, V. (Ed.), Elsevier, Amsterdam, Netherlands, ISBN: 978-0-443-29338-2, pp: 1-51.

- Owolabi, T.A. and B.A. Ayinde, 2022. Growth inhibitory and cytotoxicity effects of aqueous extract of Musanga cecropioides R. Br. Ex Tedlie (Urticaceae) stem bark. Sci. Int., 10: 94-101.

- Asma, S.T., U. Acaroz, K. Imre, A. Morar and S.R.A. Shah et al., 2022. Natural products/bioactive compounds as a source of anticancer drugs. Cancers, 14.

- Dehelean, C.A., I. Marcovici, C. Soica, M. Mioc and D. Coricovac et al., 2021. Plant-derived anticancer compounds as new perspectives in drug discovery and alternative therapy. Molecules, 26.

- Tungmunnithum, D., A. Thongboonyou, A. Pholboon and A. Yangsabai, 2018. Flavonoids and other phenolic compounds from medicinal plants for pharmaceutical and medical aspects: An overview. Medicines, 5.

- Salgado, V.G., J.N.V. Barreto, J.F. Rodríguez-Cravero, M.A. Grossi and D.G. Gutiérrez, 2025. Factors influencing the global invasion of the South American weedy species Praxelis clematidea (Asteraceae): A niche shift and modelling-based approach. Bot. J. Linn. Soc., 208: 275-289.

- Intanon, S., B. Wiengmoon and C.A. Mallory-Smith, 2020. Seed morphology and allelopathy of invasive Praxelis clematidea. Notulae Botanicae Horti Agrobotanici Cluj-Napoca, 48: 261-272.

- Liang, S., L. Wang, Z. Xiong, J. Zeng and L. Xiao et al., 2023. Anti-inflammatory phenolics and phenylpropanoids from Praxelis clematidea. Fitoterapia, 167.

- Silva, D.F., A.C.L. de Albuquerque, E. de Oliveira Lima, F.M. Baeder and A.B.H. Luna et al., 2020. Antimicrobial and anti-adherent potential of the ethanolic extract of Praxelis clematidea (Griseb.) R.M.King & Robinson on pathogens found in the oral cavity. Res. Soc. Dev., 9.

- Li, K., Z. Deng, C. Lei, X. Ding, J. Li and C. Wang, 2024. The role of oxidative stress in tumorigenesis and progression. Cells, 13.

- Janciauskiene, S., 2020. The beneficial effects of antioxidants in health and diseases. Chronic Obstructive Pulm. Dis.: J. COPD Found., 7: 182-202.

- Chibuye, B., I.S. Singh, S. Ramasamy and K.K. Maseka, 2024. Natural antioxidants: A comprehensive elucidation of their sources, mechanisms, and applications in health. Next Res., 1.

- Shih, Y.C.T., L.M. Sabik, N.K. Stout, M.T. Halpern, J. Lipscomb, S. Ramsey and D.P. Ritzwoller, 2022. Health economics research in cancer screening: Research opportunities, challenges, and future directions. JNCI Monogr., 2022: 42-50.

- Ayinde, B.A. and U. Agbakwuru, 2010. Cytotoxic and growth inhibitory effects of the methanol extract Struchium sparganophora Ktze (Asteraceae) leaves. Pharmacogn. Mag., 6: 293-297.

- Wagace, F., 2023. Cytotoxicity assessment: Methodologies and challenges. Res. Rev.: J. Pharmacol. Toxicol. Stud., 11: 12-14.

- Xu, G., X. Ye, J. Chen and D. Liu, 2007. Effect of heat treatment on the phenolic compounds and antioxidant capacity of citrus peel extract. J. Agric. Food Chem., 55: 330-335.

- Altemimi, A., N. Lakhssassi, A. Baharlouei, D.G. Watson and D.A. Lightfoot, 2017. Phytochemicals: Extraction, isolation, and identification of bioactive compounds from plant extracts. Plants, 6.

- Owolabi, T.A. and B.A. Ayinde, 2021. Bioactivity guided isolation and characterization of anti-cancer compounds from the stem of Musanga cecropioides R. Br. Ex Tedlie (Urticaceae). J. Pharmacogn. Phytochem., 10: 292-296.

- Bitwell, C., S.S. Indra, C. Luke and M.K. Kakoma, 2023. A review of modern and conventional extraction techniques and their applications for extracting phytochemicals from plants. Sci. Afr., 19.

- Yu, X., X. Tu, L. Tao, J. Daddam, S. Li and F. Hu, 2023. Royal jelly fatty acids: Chemical composition, extraction, biological activity, and prospect. J. Funct. Foods, 111.

- Tipton, A.E. and S.J. Russek, 2022. Regulation of inhibitory signaling at the receptor and cellular level; advances in our understanding of GABAergic neurotransmission and the mechanisms by which it is disrupted in epilepsy. Front. Synaptic Neurosci., 14.

- Wardini, T.H., I.N. Afifa, R.R. Esyanti, N.T. Astutiningsih and H.A. Pujisiswanto, 2023. The potential of invasive species Praxelis clematidea extract as a bioherbicide for Asystasia gangetica. Biodiversitas J. Biol. Diversity, 24: 4738-4746.

- Olawale, F., K. Olofinsan and O. Iwaloye, 2022. Biological activities of Chromolaena odorata: A mechanistic review. South Afr. J. Bot., 144: 44-57.

- Petit, R., J. Izambart, M. Guillou, J.R.G. da Silva Almeida and R.G. de Oliveira Jr. et al., 2024. A review of phototoxic plants, their phototoxic metabolites, and possible developments as photosensitizers. Chem. Biodivers., 21.

- Uğur, D., H. Güneş, F. Güneş and R. Mammadov, 2017. Cytotoxic activities of certain medicinal plants on different cancer cell lines. Turk. J. Pharm. Sci., 14: 222-230.

- Fadeyi, S.A., O.O. Fadeyi, A.A. Adejumo, C. Okoro and E.L. Myles, 2013. In vitro anticancer screening of 24 locally used Nigerian medicinal plants. BMC Complementary Altern. Med., 13.

- Hassan, S.H.A., S.W. van Ginkel, M.A.M. Hussein, R. Abskharon and S.E. Oh, 2016. Toxicity assessment using different bioassays and microbial biosensors. Environ. Int., 92-93: 106-118.

- Lee, J., 2025. Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Cell Death: Mechanisms and Implications in Pathology. In: Cell Death Regulation in Pathology, Carafa, V. and A.M. Carmona-Ribeiro (Eds.), IntechOpen, London, ISBN: 978-0-85466-966-0 .

- Kowalczyk, P., D. Sulejczak, P. Kleczkowska, I. Bukowska-Ośko and M. Kucia et al., 2021. Mitochondrial oxidative stress-a causative factor and therapeutic target in many diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci., 22.

- Chen, W., H. Zhao and Y. Li, 2023. Mitochondrial dynamics in health and disease: Mechanisms and potential targets. Signal Transduction Targeted Ther., 8.

- Anderson, J.J., T. Li and D.J. Sharrow, 2017. Insights into mortality patterns and causes of death through a process point of view model. Biogerontology, 18: 149-170.

- Xia, Y. and W.X. Wang, 2025. Development and application of cell-based bioassay in aquatic toxicity assessment. Aquat. Toxicol., 285.

- Białk-Bielińska, A., E. Mulkiewicz, M. Stokowski, S. Stolte and P. Stepnowski, 2017. Acute aquatic toxicity assessment of six anti-cancer drugs and one metabolite using biotest battery-biological effects and stability under test conditions. Chemosphere, 189: 689-698.

- Pucci, B., M. Kasten and A. Giordano, 2000. Cell cycle and apoptosis. Neoplasia, 2: 291-299.

- Gęgotek, A. and E. Skrzydlewska, 2023. Ascorbic Acid as Antioxidant. In: Vitamins and Hormones Litwack, G. and T. Lake (Eds.), Elsevier, Amsterdam, Netherlands, ISBN: 978-0-443-15768-4, pp: 247-270.

- Laitonjam, W.S., 2012. Natural Antioxidants (NAO) of Plants Acting as Scavengers of Free Radicals. In: Studies in Natural Products Chemistry, Atta-ur-Rahman (Ed.), Elsevier, Amsterdam, Netherlands, ISBN: 978-0-444-59514-0, pp: 259-275.

- Chaachouay, N., 2025. Synergy, additive effects, and antagonism of drugs with plant bioactive compounds. Drugs Drug Candidates, 4.

- Abubakar, A.R. and Mainul Haque, 2020. Preparation of medicinal plants: Basic extraction and fractionation procedures for experimental purposes. J. Pharm. BioAllied Sci., 12: 1-10.

- Eze, I.L., F.A. Onyegbule, C.O. Ezugwu, J.V. Chibuzor and O.M. Aziakpono, 2024. Phytochemical and antioxidant evaluations of Chromolaena odorata and Huntaria umbellata. J. Pharm. Res. Int., 36: 213-224.

- Lis, B. and B. Olas, 2019. Pro-health activity of dandelion (Taraxacum officinale L.) and its food products-history and present. J. Funct. Foods, 59: 40-48.

- Karimi, M.H., S. Ebrahimnezhad, M. Namayandeh and Z. Amirghofran, 2014. The effects of cichorium intybus extract on the maturation and activity of dendritic cells. DARU J. Pharm. Sci., 22.

- da Silva Mendonça, J., R. de Cássia Avellaneda Guimarães, V.A. Zorgetto-Pinheiro, C. di Pietro Fernandes and G. Marcelino et al., 2022. Natural antioxidant evaluation: A review of detection methods. Molecules, 27.

- Sharifi-Rad, M., N.V.A. Kumar, P. Zucca, E.M. Varoni and L. Dini et al., 2020. Lifestyle, oxidative stress, and antioxidants: Back and forth in the pathophysiology of chronic diseases. Front. Physiol., 11.

- Bhattacharyya, A., R. Chattopadhyay, S. Mitra and S.E. Crowe, 2014. Oxidative stress: An essential factor in the pathogenesis of gastrointestinal mucosal diseases. Physiol. Rev., 94: 329-354.

How to Cite this paper?

APA-7 Style

Owolabi,

T.A., Ayinde,

B.A. (2025). Preliminary Oncopharmacological Evaluation of Praxelis clematidea (Griseb): Growth Inhibition, Cytotoxicity, and Antioxidant Activities. Trends in Biological Sciences, 1(4), 295-305. https://doi.org/10.21124/tbs.2025.295.305

ACS Style

Owolabi,

T.A.; Ayinde,

B.A. Preliminary Oncopharmacological Evaluation of Praxelis clematidea (Griseb): Growth Inhibition, Cytotoxicity, and Antioxidant Activities. Trends Biol. Sci 2025, 1, 295-305. https://doi.org/10.21124/tbs.2025.295.305

AMA Style

Owolabi

TA, Ayinde

BA. Preliminary Oncopharmacological Evaluation of Praxelis clematidea (Griseb): Growth Inhibition, Cytotoxicity, and Antioxidant Activities. Trends in Biological Sciences. 2025; 1(4): 295-305. https://doi.org/10.21124/tbs.2025.295.305

Chicago/Turabian Style

Owolabi, Tunde, A, and Buniyamin A Ayinde.

2025. "Preliminary Oncopharmacological Evaluation of Praxelis clematidea (Griseb): Growth Inhibition, Cytotoxicity, and Antioxidant Activities" Trends in Biological Sciences 1, no. 4: 295-305. https://doi.org/10.21124/tbs.2025.295.305

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.