Genetic Diversity and Inter-Specific Interactions in Family Arecaceae

| Received 25 Jun, 2025 |

Accepted 30 Sep, 2025 |

Published 31 Dec, 2025 |

Background and Objective: Palm trees are most significant in the nutrition and ecological sustainability of man. This study aimed to evaluate the significance of taxonomic diversity and species interactions (epiphytes) among members of the Arecaceae family. Materials and Methods: Two study locations (South-Core and North-Core) at Joseph Sarwuan Tarka University, Makurdi, Benue State, Nigeria, were considered. A simple random sampling technique based on standard procedures for ecological and taxonomic assessments was employed. A transect distance of 100 by 100 m was measured in five plots in each of the study locations following the utilization of a non-destructive method of harvest. Studied species displayed varied foliar and floral macromorphological characteristics, which were qualitatively and quantitatively measured. ResμLts: Elaeis guineensiswas the most dominant (Simpson, 0.43), and richest (Magalef, 28.84) species evaluated. Cocos nucifera was the most diverse (Shannon-Weiner, 0.37) in both locations. Also, inter-specific interactions evaluated suggested most epiphytes preferred Elaeis guineensis.The most dominant, diverse, and richest epiphyte in this study was Polysticlium munitum. Analysis for carbon storage and species density showcased the ecology of species. Phylogenetic relationship revealed Cocos nucifera, Elaeis guineensis,andCycas revoluta are closely related. Conclusion: The ecological and taxonomic significance of palm species is negligible but of great impact on the ecosystem.

| Copyright © 2025 Okpara et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. |

INTRODUCTION

Palms play vital roles in cultural, medicinal, and ecological aspects of man. Members of the family Arecaceae serve both ecological and economic roles, mostly characterized by their towering, slender trunks and large, fan-like leaves. The Aceraceae are highly adaptable and can thrive in a variety of extreme climatic conditions, ranging from coastal regions to arid deserts1.

Economic species such as the oil palm (Elaeis guineensis), coconut (Cocos nucifera), and the date palm (Phoenix dactylifera) are primarily cultivated extensively for their fruit, oil, and other by-products such as fibre. Oil palm products, such as palm oil, is a major raw material used in food, cosmetics, and biofuels industries, while date palm products, especially the fruits, are a nutritious staple food in many cultures, particularly in the Northern part of Nigeria. Additionally, palms provide materials for shelter (thatching), fibre (weaving), and different forms of construction that require the use of any part of the palm tree, playing an important role in the local economy and traditional crafts2.

The cultural significance of palm trees is equally invaluable as species are utilized as symbols of peace, victory, and fertility in various traditions and religious contexts. However, the sustainability of palm tree cultivation in the Sub-Saharan Region, Nigeria, is still arguable, particularly with the level of environmental impact brought about by large-scale palm oil plantations, which have contributed a great deal to deforestation and biodiversity loss. Conservation efforts and sustainable farming practices are increasingly being emphasized to mitigate these impacts and preserve the ecological and economic benefits obtained from the cultivation of species in the Arecaceae3.

The ecological and taxonomic assessment of palm species is a crucial aspect of study in which significant implications for biodiversity conservation, agricultural productivity, and sustainable development is being emphasized. The introduction of large-scale Palm cultivation impacts ecosystems and economies, providing a range of products including oil, fruits, and fibres. Evaluating the taxonomic diversity, morphological variation, biomass, evolutionary lineage, and ecological interactions, especially interactions with epiphytes, allows researchers to understand the adaptability of species to environmental changes, how to develop new sustainable farming practices, food supply chain improvement, and contribution to manufacturing industrial4. The data generated can also help environmental specialists make informed decisions on various conservation strategies associated with the global sustainable development goals.

Phenotypic assessments involving macromorphological characters of species in this context palm trees which involve the examination of observable traits such as tree height, leaf morphology, fruit, and productivity. These traits are influenced by both genetic factors and environmental conditions. The integration of taxonomic, ecological, and molecular data enables the development of more robust strategies for improved cultivation and sustainable conservation practices5. In addition, Palm trees hold cultural significance in many regions of the world, such as the Middle East nations and Northern Africa, including Sub-Saharan countries like Nigeria. Studies on the genetic and phenotypic diversity of palm species have also revealed a great contribution to the preservation of indigenous knowledge and practices. Research by Baker and Dransfield6 on the Genera Palmarum: Progress and prospects in palm systematics, highlighted the traditional uses of these species and the need to conserve its genetic resources for future generations. Moreover, conservation efforts are increasingly focusing on the preservation of wild palm species. Genetic assessments can help identify genetically distinct populations that may be at risk of extinction, informing the improvement of existing conservation strategies. A recent study by Salako et al.7 on the traditional knowledge and cultural importance of Borassus aethiopum Mart. in Benin: Interacting effects of socio-demographic attributes and multi-scale abundance ofBorassus aethiopum using both genetic and phenotypic data to develop conservation plans, aided the protection of valuable species from habitat loss and over-exploitation.

The taxonomic and ecological roles of palm tree species are integral to understanding their diversity, adaptability, and potential for sustainable cultivation improvements. The recent advancements in molecular and genomic tools, has enabled researchers continue to uncover the ecological significance of each trending traits, ensuring the sustainable utilization and conservation of these economic species.

This gap in knowledge on the relationship between morphology and evolution in palm species hamper efforts to improve the species for better yield, disease resistance, and environmental adaptation. Without comprehensive information on inter specific relationship and phenotypic characterization, breeding programs cannot effectively select superior palm varieties, and conservation strategies may fail to protect genetically valuable populations. Additionally, the impact of environmental factors on the diversity of palms remains poorly understood, which is fundamental to sustainable cultivation and use. Therefore, the need for extensive research to fill this vacuum would provide valuable insights for improvement of sustainable agricultural practices and conservation policies in Nigeria.

This study aimed to evaluate the significance of taxonomic diversity and species interactions (epiphytes) among members of Arecaceae. The specific objectives are to:

| • | Determine the taxonomic diversity in both arecaceae and epiphytic species encountered | |

| • | Identify the evolutionary relationship among palm species using molecular characters | |

| • | Identify the ecological roles of density and biomass | |

| • | Evaluate the ethnobotanical significance and ecological interactions of epiphytes and Palm trees |

MATERIALS AND METHODS

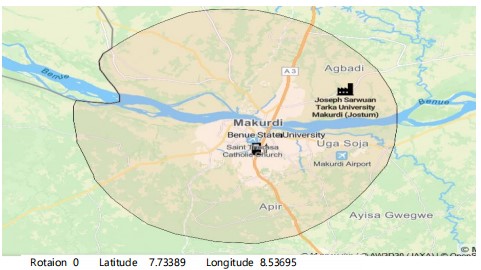

Study area: The study was carried out in Joseph Sarwuan Tarka University, Makurdi, Benue State, Nigeria. The study location is situated in North Central Guinea Savannah Region of Nigeria, On Latitude: 7°44'15"N and Longitude: 8°31'17"E. Benue State is bounded on the East by Enugu State, on the South by Ebonyi, Cross River States and Cameron Republic; on the West by Kogi State and on the North by Nasarawa and Taraba States. The state has a total land area of 3,993.3 km2 with an estimated population of 4,253,641 million people8. The soil composition on the area varies from sandy to loamy and is surrounded by vegetations, building and lakes. The occupations of majority of inhabitants are farming. The climatic condition of the state is characterised by an oppressive precipitation season which begins from April to October, with the most wet days in September. The hottest seasons last from April with average temperature above 92 and 76 F. The cool seasons lasts from June to December, ranging from 86 to 64 F. The length of day does not vary significantly, in 2024 the shortest day was recorded in December 21, with 11 hrs, 41 min, the longest day in June with 12 hrs 34 min of daylight.

Table 1 presents the common names of species collected, subfamily, tribe, subtribe, locality, and coordinates of collection sites in this study. Five species representing three subfamilies, five tribes, and five subtribes, respectively, were collected from all study locations. Figure 1 shows the map of Makurdi Local Government Area in Benue State, Nigeria, representing the study location (Joseph Sarwuan Tarka University, Makurdi) of the collected samples used in this study.

Plant collection and survey: The study was carried out from the month of May to December, 2024. A simple random sampling method based on standard procedures for ecological diversity and morphological variation assessments was employed. Various field surveys aimed to identify and document the dominance, richness, and evenness of the palm species were carried out. The frequency of species distribution and abundance was inventoried. Relevant information on the leaf, fruit, and bark has been inventoried. Line transects measuring about 100 by 100 m intervals involving 2 sampling locations were used. Species locality and coordinates were also recorded.

|

| Table 1: | Showing location and locality of species collected | |||

| Species | Common name | Sub-family | Tribe | Sub-tribe | Locality | Coordinates |

| Dypsis lutescens (H. Wendl) | Areca | Arecoideae | Areceae | Dypsidinae | South-Core/ North-Core |

745'59"N, 837''23'E |

| Cycas revoluta Thunb. | Cycas/Sago palm | Coryphoideae | Cycadeae | Cycasinae | South-Core/ North-Core |

745' 549"N, 837'4'E |

| Elaeis guineensis Jacq. | Oil palm | Arecoideae | Areceae | Elaeidinae | South-Core/ North-Core |

745 49"N, 837'4'E |

| Cocos nucifera L. | Coconut | Arecoideae | Cocoseae | Attaleinae | South-Core/ North-Core |

745'579"N. 837'2'E |

| Borassus aethiopum mart. | African fan palm | Borassoideae | Borasseae | Borassinae | South-Core/ North-Core |

745' 49"N. 837'4'E |

| Table 2: | RAPD markers | |||

| RAPD marker | Sequence | Temperature (°C) |

| OPA-04 | AATCGGGCTG | 42.7 |

| Table 3: | RAPD-PCR thermal profile | |||

| Operation stages | Temperature (°C) | Time | Cycles |

| Initial denaturation | 95 | 5 min | 1 |

| Denaturation | 95 | 4 sec | |

| Annealing | 38-45 | 6 sec | 4 |

| Elongation | 72 | 2 min | |

| Final elongation | 72 | 5 min |

Taxonomic diversity study: The diversity of Palms and Epiphytes was analysed using biodiversity indices such as Shannon-Weiner index (H’) and Simpson’s Diversity index (D), Magalef and Pielou’s evenness. These indices were used to assess species dominance, diversity, richness, and evenness across sampled species9. A comparative analysis of species dominance and distribution on both palm and epiphytes was conducted to determine if tree species and epiphytes interacted within micro-environmental conditions and whether these interactions influenced species abundance and carbon storage.

Morphological studies: Descriptive macro-morphological features such as leaflet length, area, and lamina were measured using a thread and a meter rule. Variation in the descriptive characters such as leaf shape, apex, base, surface above and beneath, margin, venation, arrangement, blade, midrib, petal shape, petal colour, sepal shape, sepal colour, sepal arrangement, petal arrangement, floral position, bract shape, bract shape and colour, spathe shape and colour, bract arrangement, spathe arrangement were inventoried for palm species especially10.

Molecular studies

DNA extraction: Plant DNA was extracted from freshly harvested plant leaflets using the Edwards protocol11. A measurement of 2 ul of Edwards buffer was added to 5-1 mg of plant leaf tissue in a 1.5 mL micro-centrifuge tube. The tissue was manually crushed for 5 min using a plastic pestle. An additional 3 ul of Edwards buffer was added, and the crushing continued for another 5 min. The volume was adjusted to 1 ul by adding 5 ul of Edwards buffer. The sample was vortexed for 15 sec and incubated at 1°C for 1 min. The sample was centrifuged at 2 rpm for 1 min in a micro-centrifuge. A 5 ul of the supernatant was transferred to a new 1.5 mL microcentrifuge tube and centrifuged again at 2 rpm for 1 min, transferring 4 ul of the supernatant to another new 1.5 mL microcentrifuge tube. A 4 ul of ice-cold isopropanol was added to the supernatant, and the sample was gently inverted 5 times, then incubated at room temperature for 1 min. The sample was centrifuged at 12 rpm for 1 min, the supernatant was discarded, and 5 ul of 7% e thanol was added to the pellet without disturbing it. The sample was inverted 5 times, and the ethanol was discarded, repeating the wash step. The pellet was air-dried for 1 min and resuspended in 5 ul of Tris EDTA buffer.

Random Amplified Polymorphic DNA-Polymerase Chain Reaction (RAPD-PCR): Table 2 shows the sequencing procedure using RAPD marker OPA-4 with the sequence code AATCGGGCTG at an annealing temperature of about 42.7°C.

| Table 4: | PCR reaction mix | |||

| Component | Volume (ul) | Final conc. |

| 5xFIREPol®MasterMixReady | ||

| To load | 4 | 1x |

| Forward primer (1 pmoL/ul) | 0.2 | 0.1 μM |

| Reverse primer (1 pmoL/ul) | 0.2 | 0.1 μM |

| Template DNAxul | 5 | 25 ng/ul |

| Add H2O upto 2 ul | 1.6 | - |

Table 3 represents the RAPD-PCR thermal profile and operation stages. The initial denaturation temperature captured was 95°C at 5 min in 1 circle. At the main denaturation stage temperature obtained was 95°C at 4 sec each in 4 circles. Annealing temperature range was between 38-45°C at 6 sec each in 4 circles. The initial DNA elongation temperature was 72°C at 2 min in 4 cycles. The final DNA denaturation stage was obtained at 72°C for 5 min each of 4 cycles.

Table 4 represents the PCR reaction components used during analysis. The 5x FIREPol® Master Mix Ready to load isa pre-mixed solution used in PCR (Polymerase Chain Reaction) to obtain a simplified process.It is composed of all the necessary reagents for PCR except DNA template, primers, and water. The 5x FIREPol® Master Mix Ready to load used was a measure of (4 ul) volumes at a 1 times concentrated solution. While the primers were composed of 2 volumes of Forward primer (1 pmoL/ul) at 0.1 μM final concentration and 2 volumes of Reverse primer (1 pmoL/ul) at 0.1 μM final concentration. The DNA template used was 5 volumes in 25 ng/ul concentration. Finally, 1.6 ul volumes of water up to 2 ul was added12.

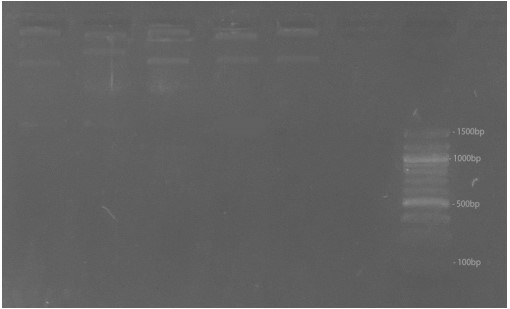

Gel electrophoresis A 5 mL solution of 1x TBE was prepared and 0.75 g of agarose gel was added. The mixture was heated in the microwave on high for 1 min to melt the gel. Ethidium bromide was added to a final concentration of 1:2, (3 ul). The solution was allowed to cool before being poured into a casting tray. Once set, the gel was transferred to a gel tank and covered with 1x TBE buffer. Amplification products (15 ulaliquots) were loaded into the wells and the gel was run at 1V for 3 min. The resulting bands were visualized under UV light using a gel documentation system13.

Gel image and molecular data analysis: The PyElph version 1.4 was used to analyse the banding pattern of the various RAPD markers. The Software was used to draw the Dendrogram using the UPGMA method14.

Biomass and carbon uptake estimation: Biomass and carbon stock of palm species at Joseph Sarwuan Tarka University (JOSTUM) were measured. Non-destructive technique was used for data collection, and the calculations of aboveground biomass (AGB) were done following the allometric equation reported by McPherson et al.15.

The aboveground biomass (AGB) of palm trees in each study location was estimated from a combination of variables such as Wood density (ρ), diameter at breast height (cm), and height of tree (m), Wood density (ρ) serves as an important predictive variable used in all regression models for the estimation of trees biomass. AGB (Mg/ha) representing the aboveground tree biomass, where α and β are the model coefficients, D (cm) is the tree trunk diameter, H (m) is the total tree height, ρ (in g/cm) is the wood specific gravity distribution.

All the Models used for biomass estimation were reported by Daa-Kpode et al.16 and Eneji et al.17, they are the standard models for measuring biomass in tropical forests. However, carbon stock evaluations are essentially derived from live or coarse woody debris biomass by assuming that 50% of the biomass is made up carbon18,19.

Ethnobotanical survey of epiphytes on palm trees studied

Relative frequency of citation (RFC): The relative importance of species was determined using the formula:

Where:

| Fc | = | Respondents who identified a particular species | |

| N | = | Number of the respondents20 |

Fidelity level (FL): The relative healing potential of a particular species against a particular ailment was determined using the formula:

Where:

| Ns | = | Frequency of citation of a species use for a particular ailment | |

| N | = | Number of citations of a particular species of interest20 |

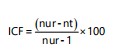

Informant consensus factor (ICF): The ICF was determined for each category of ailment to identify the relationship between respondents and reported epiphytic plants used to the cure ailment.

The ICF was calculated using the formula:

|

Where:

| nur | = | Number of citations for each ailment | |

| nt | = | Number of species reported to cure that ailment20 |

RESULTS

Diversity study

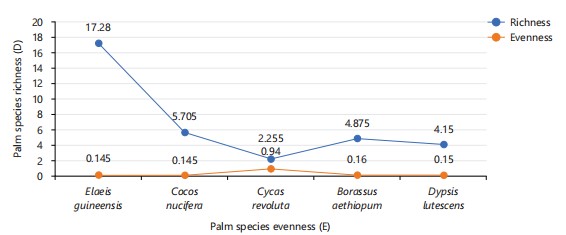

Diversity of palm species: The data in Table 5 represents the relative frequency and relative dominance evaluated for five palm species in two study stations (South-Core and North-Core) axis of Joseph Sarwuan Tarka University. In this study, Cycas nucifera was the most Abundant (29.17), followed by Cocos nucifera (20.83) and Elaeis guineensis (20.83). others include Borassus aethiopum (6.17) and Dypsis lutescens (12.50). Table 6 represents diversity indices evaluated in two stations. Species richness (Magalef) was highest in Elaeis guineensis (28.84) at the South-Core study location, and in the North-Core, highest in Cocos nucifera (6.43). Species dominance (Simpson’s diversity index) was calculated to be highest in Elaeis guineensis (0.43) at South-Core and highest in Cocos nucifera (0.11) at South-Core. Diversity indices (Shannon-Weiner) revealed in South-Core Cycas revoluta (0.29) was the highest, and Cocos nucifera (0.37) at North-Core. Species evenness was recorded equal values at North-Core and the lowest value in Cocos nucifera (0.21) at North-Core. Highest evenness in Cycas revoluta at South Korea. Figure 2 is a linear graph showing the relationship between species richness and evenness among the studied palm species. The richest species represented in the graph was Elaeis guineensis, while the most evenly distributed species was Cycas revoluta.

|

| Table 5: | Showing the relative frequency and relative abundance of studied species | |||

| Species/study location | South-Core | North-Core | Relative frequency | Relative abundance |

| Elaeis guineensis | 5 | 5 | 5 | 20.83 |

| Cocos nucifera | 4 | 6 | 5 | 20.83 |

| Cycas revoluta | 12 | 2 | 7 | 29.17 |

| Borassus aethiopum | 6 | 2 | 4 | 16.67 |

| Dypsis lutescens | 4 | 2 | 3 | 12.5 |

| Total | 24 | 100 |

| Table 6: | Showing the diversity indices of palm trees at each study location | |||

| Number of species | Magalef (D) | Simpson | Shannon weiner (H1) | Evenness | ||||||

| Species/study location | S | N | S | N | S | N | S | N | S | N |

| Elaeis guineensis | 5 | 5 | 28.84 | 5.72 | 0.43 | 0.7 | 0.28 | 0.36 | 0.08 | 0.21 |

| Cocos nucifera | 4 | 6 | 4.98 | 6.43 | 0.002 | 0.11 | 0.15 | 0.37 | 0.09 | 0.2 |

| Cycas revoluta | 12 | 2 | 1.19 | 3.32 | 0.023 | 0.1 | 0.29 | 0.25 | 1.67 | 0.21 |

| Borassus aethiopum | 6 | 2 | 6.43 | 3.32 | 0.005 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.25 | 0.11 | 0.21 |

| Dypsis lutescens | 4 | 2 | 4.98 | 3.32 | 0.002 | 0.1 | 0.15 | 0.25 | 0.09 | 0.21 |

| S: South-Core and N: North-Core | ||||||||||

| Table 7: | Showing diversity indices of epiphytes at study locations | |||

| Species | Magalef (D) | Simpson | Shannon-weiner (H1) | Pileou evenness (E) |

| Ficus benghalensis L. | 3.32 | 0.23 | 0.6 | 0.21 |

| Polystichum munitum (Kaulf.) C. Presl | 5.72 | 0.9 | 0.11 | 0.16 |

| Gomphrena serrata L. | 4.19 | 0.45 | 0.8 | 0.17 |

| Crinum asiaticium L. | 4.98 | 0.68 | 0.1 | 0.16 |

| Setaria barbata (Lam.) Kunth | 3.32 | 0.23 | 0.6 | 0.21 |

| Litsea bindonaina (F. Muell.) F. Muell | 4.19 | 0.45 | 0.8 | 0.17 |

| Dracaena fragrans (L.) Ker. Gawl. | 3.32 | 0.23 | 0.6 | 0.21 |

| Azadirata indica A. Juss | 4.98 | 0.68 | 0.1 | 0.16 |

| Spermacoce verticillata L. | 3.32 | 0.23 | 0.6 | 0.21 |

| Tridax procumben L. | 4.19 | 0.45 | 0.8 | 0.17 |

| Commelina diffusa Burm. F | 3.32 | 0.23 | 0.6 | 0.21 |

| Ficus regiosa L. | 4.19 | 0.45 | 0.8 | 0.17 |

| Ficus macrophylla Desf. ex. pers. | 4.19 | 0.45 | 0.8 | 0.17 |

| Lepturus repens (G. Forst.) R. Br. | 4.19 | 0.45 | 0.8 | 0.17 |

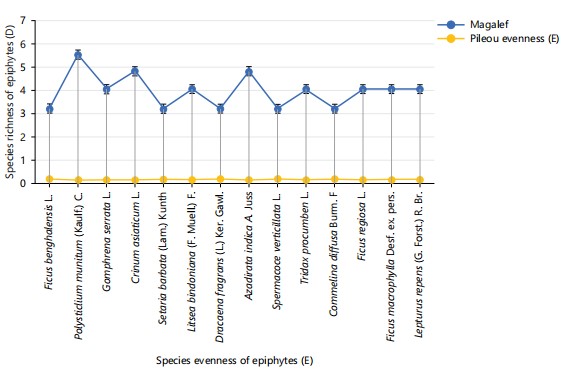

Diversity of epiphytes: The data presented in Table 7 reveals the Magalef index for epiphytes inhabiting palm trees at study locations. The Magalef index measures species richness, and in this study, shows that Polystichum munitum had the highest richness value of 5.72. This indicates that Polystichum munitum contributes significantly to the diversity of the epiphytic community. Following closely, Crinum asiaticum and Azadirachta indica also demonstrated relatively high richness values of 4.98 each, indicating they are prominent members of the ecosystem. In contrast, species such as Ficus benghalensis, Setaria barbata, and Spermacoce verticillata, each with a lower richness value of 3.32, contribute less to the species richness but still add to the overall diversity. The Simpson index provides insight into species dominance within the community, with higher values indicating a greater likelihood of encountering the same species repeatedly.

|

Polystichum munitum stands out again with a Simpson index of 0.9, highlighting it as a dominant species within this ecosystem. Crinum asiaticum and Azadirachta indica also show substantial dominance, with Simpson values of 0.68, signifying their strong presence in the community. Conversely, species such as Ficus benghalensis, Setaria barbata, and Spermacoce verticillata, with Simpson values of 0.23, are less dominant and likely encountered less frequently. The Shannon-Weiner index, which accounts for both species’ abundance and evenness, suggests moderate diversity within the Epiphyte community. Polystichum munitum had the highest Shannon-Weiner index at 0.11, followed by Crinum asiaticum and Azadirachta indica at 0.1 each, indicating they have relatively higher diversity. However, these values are still low, pointing to limited diversity within individual species. Species like Ficus benghalensis, Setaria barbata, and Spermacoce verticillata, had the lowest Shannon-Weiner values at 0.6, exhibited the least diversity, possibly due to smaller populations or more restricted distributions. The evenness values, measured by Pielou’s index, reveal that the Epiphyte community was not evenly distributed. Most species had low evenness values, ranging between 0.16 and 0.21. Ficus benghalensis, Setaria barbata, and Spermacoce verticillata showed the highest evenness at 0.21, indicating a relatively more balanced distribution among these species. Meanwhile, Polystichum munitum, with an evenness value of 0.16, showed a more uneven distribution, likely reflecting its dominance and more extensive populations within the ecosystem.

Figure 3 shows a linear graph of richness and evenness among epiphytic species studied. Polystichum munitum had the richest species and evenness indices in all study locations. Figure 4-15 show photographs of studied epiphytes in the microhabitat, mostly found growing on the bark of oil palm (Elaies guineensis) see appendix. The epiphytes include: Fig. 4 shows Commelina diffusa, Fig. 5 shows Lepturus repens, Fig. 6 shows Ficus benghalensis, Fig. 7 shows Litsea bindoniana, Fig. 8 shows Polystichum munitum, Fig. 9 shows Ficus religiosa, Fig. 10 shows Dracaena fragrans, Fig. 11 shows Gomphrena serrata, Fig. 12 shows Ficus macrophylla, Fig. 13 shows Setaria barbata, Fig. 14 shows Azadirachta indica, and Fig. 15 shows Tridax procumbens. Photographic images of epiphytes at the study sites were captured using an Infinix X650B (version 9).

|

|

|

|

Comparative morphological characterization of palm species: The qualitative foliar characteristics of the studied species include: The leaflet shape, which ranges from lanceolate in Elaeis guineensis, Cocos nucifera, and Cycas revoluta to falcate in Borassus aethiopum; Leaflet apex mostly acuminate in Elaeis guineensis, Cocos nucifera, acute in Cycas revoluta, and Trifid in Dypsis lutescens, and oblanceolate in Borassus aethiopum, base of the leaves varied from amplexicaul in Elaeis guineensis, Cocos nucifera to Pseudo petiolate in Cycas revoluta, Sagittate in Borassus aethiopum and pinnate in Dypsis lutescens.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Table 8: | Chromosome characteristics of palm species sampled from JOSTUM | |||

| Species | Chromosomes (2n) | Chromosome type |

| Elaeis guineensis | 16 | Diploid |

| Cocos nucifera | 32 | Diploid |

| Cycas revoluta | 22 | Haploid |

| Borassus aethiopum | 32 | Diploid |

| Dypsis lutescens | 32 | Diploid |

The leaflet surface was mostly glabrous except in Borassus aethiopum (Scabrous) and Dypsis lutescens (Glossy). The texture of leaves in all studied species was majorly Coriaceous, the leaflets in most species were pinnate except in Borassus aethiopum, which has shape as Costa palmate. The margins in all were serrated except in Borassus aethiopum (dentate) and Granulate. The examined venation was parallel, leaflet arrangement alternate; except in Borassus aethiopum and Dypsis lutescens uniquely crown shaft arrangement, there is variation in leaflet blade ranging from Linear-Lanceolate in Elaeis guineensis, Ligulate in Cocos nucifera, Pinnatifid in Cycas revoluta, Oblanceolate in Borassus aethiopum and Dypsis lutescens possess arching, pinnately compound leaves with leaflets arranged in a V-shape. all the midribs are prominent except in Borassus aethiopum (Grooved). The stem characteristics in studied species, reveals that almost all species encountered has Columnar stem shape except Cycas revoluta which has a cylindrical stem shape. The stem types are mostly not branched except in Elaeis guineensis and Borassus aethiopum which possess a single stem type. Stem position in all species studied were erect. The Node of stems were mostly solitary except in Cycas revoluta which has a Panchycalous nodal system. Fruit sizes range from the smallest in Elaeis guineensis (2 cm) to the largest in Cocos nucifera. A 2 m Fruit shape may be Oval in Elaeis guineensis, Ovoid or ellipsoid in Cocos nucifera, rounded cone shape in Cycas revoluta, large drupe in Borassus aethiopum and spherical in Dypsis lutescens, rounded or cone-shaped in Cycas revoluta, large drupe in Borassus aethiopum, and spherical in Dypsis lutescens.

All studied species possessed uniform petal shapes, ranging from ovate to oval in all except in Cycas revoluta, which bears a cone or triangular-shaped petal. Petal texture varied from velvety in Elaeis guineensis and Cocos nucifera, smooth and wavy in Dypsis lutescens. Sepal arrangement trivalvate in Elaeis guineensis and Cocos nucifera and tricuspidate in Dypsis lutescens. Petal arrangement triangular and Vexillary in Dypsis lutescens. inflorescence: Floral arrangement subterminal in Elaeis guineensis, Infra-foliar in Cocos nucifera, and cauliflorous in Borassus aethiopum. The floral characteristics required for delimitation of the studied species show that Cycas revoluta has a dark brown, triangular-shaped bract with Coriaceous texture, the bract arrangement is Imbricate with upright floral position. Spathe colour dark brown and ovate shaped, spathe texture glabrous with an overlapping arrangement, while Borassus aethiopum possesses a reddish purple ovate shaped bract with texture chartaceous, rosulately arranged. Spathe character is dark brown and cylindrical in shape. Spathe texture glabrous, enclosing with a terminal floral position.

Molecular characterization

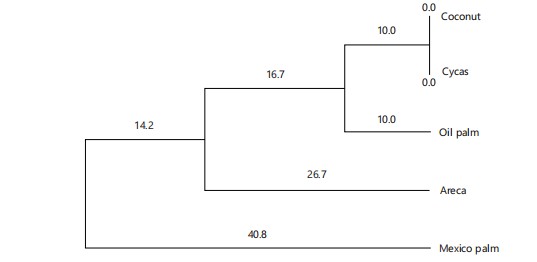

Chromosomal variance and evolutionary relationship: Table 8 shows the chromosomal characteristics in five palm species studied; all species were diploid in chromosomal characteristics except Cycas revoluta, which had a haploid chromosome. Figure 16 shows the result for genetic diversity analysis of five palm species using RAPD with the OPa-4 marker. The banding pattern of the various RAPD markers showed the highest in Elaeis guineensis. The Dendrogram in Fig. 17 shows the evolutionary relationship where four clusters were produced; the first cluster includes Cocos nucifera and Cycas revoluta. The second group comprises Elaeis guineensis, the third group includes the Borassus aethiopum, while the fourth group is composed of Dypsis lutescens only. Figure 18-23 shows photographs of the studied palm species in various locations visited on campus. Figure 6shows Cocos nucifera (Coconut), Fig. 7 shows Cycas revoluta (Cycas), Fig. 8 shows Elaeis guineensis (African Oil Palm), Fig. 9 and 10 shows Borassus aethiopum (African Fan Palm), Fig. 11 shows Dypsis lutescens (Areca), respectively.

|

|

|

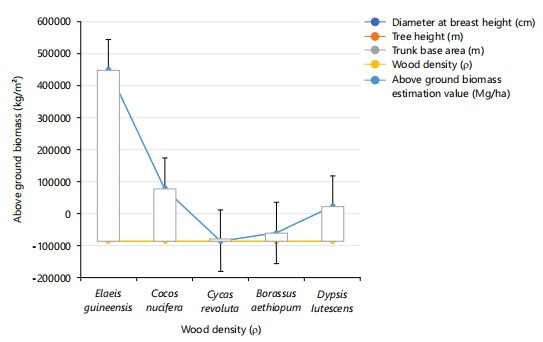

Biomass estimation: Table 9 shows the above-ground biomass estimation of the studied species. Elaeis guineensis had 26 average number of leaves, with a diameter 59.8 cm, an average tree height of 36.6 m, a trunk base area of 23.8 cm, density 18.2 cm, biomass 466121.48 kg/m2. Cocos nucifera had 32 leaves, with a 49.4 tree diameter, 36.72 m as tree height, trunk base 26.4 cm, a density 19.6 cm, and above ground biomass of 142398.77 kg/m2. Cycas revoluta had 33 leaflets, tree diameter 19, tree height 2.57, 4.4 m

|

|

|

| Table 9: | Above-ground biomass estimation values (mg/ha) of selected plant species with corresponding number of leaves, diameter at breast height (cm), tree height (m), trunk base area (m²), and wood density (ρ) | |||

| Species | Number of leaves |

Diameter at breast height (cm) |

Tree height (m) |

Trunk base area (m) |

Wood density (ρ) |

Above-ground biomass estimation value (mg/ha) |

| Elaeis guineensis | 26 | 59.8±14.53 | 36.60±6.54 | 23.80±3.34 | 18.20±1.78 | 466121.48 |

| Cocos nucifera | 32 | 49.40±11.14 | 36.72±1.69 | 26.40±4.97 | 19.60±5.17 | 142398.77 |

| Cycas revoluta | 33 | 19.00±2.80 | 2.57±37.00 | 4.40±1.14 | 2.20±44.00 | 249.36 |

| Borassus aethiopum | 21 | 8.50±7.00 | 3.32±7.00 | 3.50±7.00 | 24.50±7.00 | 21369.98 |

| Dypsis lutescens | 4 | 4.40±5.30 | 49.28±5.75 | 21.60±3.50 | 22.00±3.16 | 93393.33 |

| Mean±Standard Error | ||||||

trunk base area, density 2.2 m, and biomass of 249.36 kg/m2. Borassus aethiopum had 21 average of leaves, 8.5 m, tree height 3.32 m, a trunk base 4.4 m, a density 2.2, and biomass of 2.49.36 kg/m2. Dypsis lutescens had 4 average number of leaves, 4.4 m diameter, tree height of 49.28 m, trunk base area of 21.6 m, and a density of 22 cm, biomass 933.93.33 kg/m2. Elaeis guineensis had the highest biomass in this study followed by Borassus aethiopum (213,69.98 kg/m2), the least tree biomass was recorded in Cycas revoluta (249.36 kg/m2). Figure 24; presents a linear graph showing the relationship between morphological characteristics (diameter, tree height, trunk base area, above-ground biomass) and species density of the Palm species studied. The prominent characteristics displayed were only above-ground biomass and species density. Evidently displaying a relationship and possible prediction of the impact of biomass on the density of trees, with Cycas revoluta and Borassus aethiopum having a very close relationship.

|

|

|

|

|

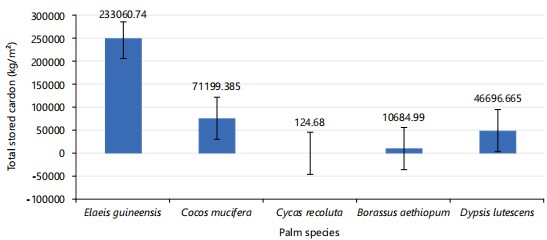

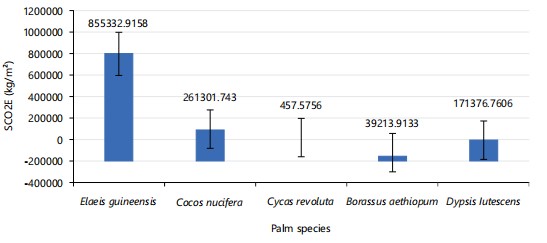

Carbon uptake estimation: Figure 25 shows is a bar chart showing the total sequestered carbon in palm species studied, Elaeis guineensis (233060.74 kg/m2) stored the most organic carbon, followed by Cocos nucifera (71199.39 kg/m2), Dypsis lutescens (46696.67 k g/m2), Borassus aethiopum (10684.99 kg/m2), and Cycas revoluta (124.68 kg/m2), which stored the least quantity of carbon. Figure 26 shows Elaeis guineensis (855332.92 kg/m2) sequestered the most carbon dioxide equivalent, followed by Cocos nucifera (261301.74 kg/m2), Dypsis lutescens (171376.76 kg/m2), Borassus aethiopum (39213.91 kg/m2), and Cycas revoluta (457.76 kg/m2) which sequestered the least quantity of SCO2E recorded.

Ethnobotanical survey on epiphytes

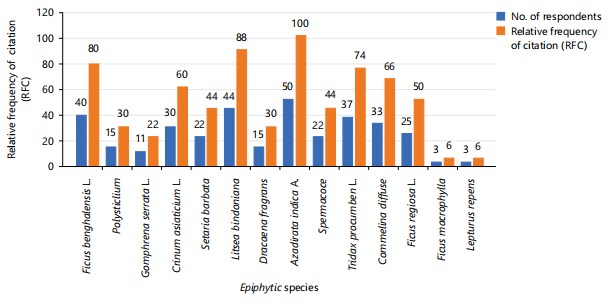

Relative frequency of citation: The data in Fig. 27 shows the number of people who mentioned each plant and the frequency with which each was cited in the ethnobotanical survey. Azadirachta indica was the most frequently mentioned, with 50 respondents citing it, giving it a 100% citation frequency. This indicates that Azadirachta indica is very significant and well-known among the University host community. Litsea bindoniana had 44 mentions, resulting in an 88% citation frequency, making it the second most recognized plant. This high frequency suggests that Litsea bindoniana is also an important plant in the area. Ficus benghalensis received 40 mentions, giving it an 80% citation frequency, which is also quite high. Tridax procumbens was mentioned by 37 respondents, resulting in a citation frequency of 74%. Commelina diffusa had 33 mentions, giving it a citation frequency of 66%, indicating it is fairly familiar to the respondents. Crinum asiaticum was cited by 30 respondents, resulting in a 60% frequency, which is moderate. Setaria barbata and Spermacoce verticillata each had 22 mentions, with a 44% citation frequency. Polystichum munitum and Dracaena fragrans were both mentioned by 15 respondents, with a frequency of 30%. Ficus regiosa received 25 mentions, which gives it a 50% citation frequency, showing some familiarity among respondents. Gomphrena serrata had 11 mentions, with a 22% frequency, suggesting it is less commonly recognized. Ficus macrophylla and Lepturus repens were the least mentioned plants, each with only 3 mentions and a citation frequency of 6%. Overall, Azadirachta indica and Litsea bindoniana stand out as the most recognized, while Ficus macrophylla and Lepturus repens are the least known.

|

|

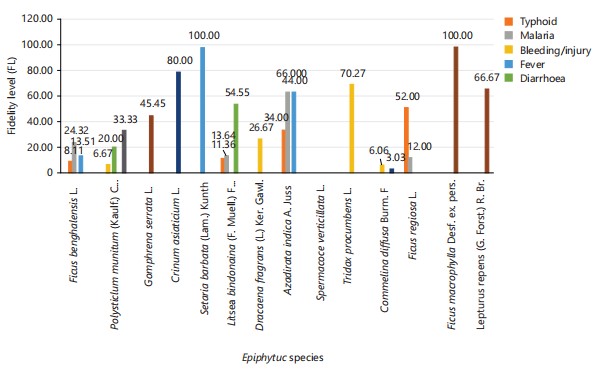

Fidelity level: Figure 28 shows the fidelity levels of different plant species and their reported effectiveness in treating various ailments. Ficus benghalensis is noted primarily for malaria treatment, with a 24.32% fidelity level, and also shows some use in treating typhoid and fever, though it is not used for other listed ailments. Polystichum munitum has notable use in treating stomach ache and sore

throat, with fidelity levels of 20 and 33.33%, respectively. Gomphrena serrata stands out with a high-fidelity level of 45.45% for skin infections but is not used for other conditions in this study. Crinum asiaticium has a significant 80% fidelity level for stomach ache, indicating a strong association with this treatment. Setaria barbata shows a unique use, with a 100% fidelity level for treating fever, implying its primary use in this context.

Litsea bindoniana shows a diverse range of uses, particularly for diarrhea (54.55%), malaria (13.64%), and typhoid (11.36%), suggesting versatility across ailments. Dracaena fragrans is most notably used for bleeding or injury treatment, with a 26.67% fidelity level, though it is not applied to other conditions. Azadirachta indica has one of the highest fidelity levels for both malaria and fever, each at 64%, and also shows a 34% fidelity level for typhoid, making it widely trusted for multiple conditions. Tridax procumbens has a 70.27% fidelity level for treating bleeding or injury, highlighting its specialization in this area. Commelina diffusa shows low fidelity for bleeding (6.06%) and stomach ache (3.03%), suggesting it is not highly relied upon for specific ailments.

Ficus regiosa has a high-fidelity level of 52% for treating typhoid, and a smaller use (12%) for malaria, marking it as useful for these particular conditions. Ficus macrophylla is notably used exclusively for skin infections with a 100% fidelity level, indicating a strong association with this treatment. Similarly, Lepturus repens has a significant 66.67% fidelity level for skin infections, but like Ficus macrophylla, it is not used for any other conditions. The data overall suggests that each plant species has unique uses, with some, like Azadirachta indica, being versatile across multiple ailments, while others, like Setaria barbata, serve highly specific purposes.

Informant consensus factor: The informant consensus factor (ICF) for various plant species and their reported effectiveness in treating specific ailments. Ficus benghalensis has high consensus levels across multiple ailments, with 91.67% for both typhoid and malaria, and 94.44% for fever, indicating that it is widely recognized for these treatments. Polystichum munitum shows a strong consensus for treating sore throat, with 100% ICF, while it also has a significant frequency for treating stomach ache at 92.86%. Gomphrena serrata is primarily noted for its effectiveness in treating skin infections, with an 80% consensus level, although it is not recognized for other ailments in this study. Crinum asiaticium is reported with a high consensus for treating skin infections, with 96.55%, highlighting its specific application in this area. Setaria barbata has a notable consensus of 90.47% for fever, indicating it is recognized as an effective treatment for this condition. Litsea bindoniana exhibits a high level of consensus for both typhoid and diarrhea, at 93.02 and 97.67%, respectively, showing its broad application in treating these ailments. Dracaena fragrans has a specific consensus for bleeding or injury, with an 85.71% ICF, suggesting its reliability in this area. Azadirachta indica is highly regarded for treating typhoid and fever, with consensus levels of 93.88 and 95.92%, respectively, underscoring its versatility in traditional medicine. Spermacoce verticillata shows no reported consensus for any ailment, indicating it may not be recognized in the community for medicinal purposes. Tridax procumbens has a significant consensus of 94.44% for treating bleeding or injury, marking it as a trusted option for this issue. Commelina diffusa is noted for its effectiveness in treating malaria and skin infections, with consensus levels of 93.75 and 96.88%, respectively, showing its importance in traditional healing practices. Ficus regiosa has high consensus levels for both typhoid and malaria at 87.50%, suggesting it is also valued for these treatments. In contrast, Ficus macrophylla and Lepturus repens show no consensus for any ailments, indicating that these species may not hold significant medicinal value in the studied context. Overall, the table highlights that certain species, such as Ficus benghalensis, Azadirachta indica, and Litsea bindoniana, are highly regarded for their effectiveness against specific ailments, reflecting their importance in traditional medicinal practices.

DISCUSSION

The findings from the genetic and phenotypic assessments of palm tree species reveal significant insights into the diversity, adaptability, and potential for improvement of these vital plants. The taxonomic and geographical data collected from the JOSTUM campus provide a comprehensive overview of the palm species sampled, highlighting the diversity and distribution of these vital plants. The presence of Coconut (Cocos nucifera), Oil Palm (Elaeis guineensis), Areca Palm (Dypsis lutescens), Cycas (Cycas revoluta), and African Fan Palm (Borassus aethiopum) in this finding is consistent with research by Smith et al.21, which emphasizes the importance ecological versatility of species across tropical and subtropical regions.

Recent studies have focused on the genetic characterization of palm tree species using molecular markers such as simple sequence repeats (SSRs) and Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms (SNPs). These markers provide detailed insights into the genetic variability within and between palm populations. For instance, research by Panwar et al.22. The SSR markers to evaluate the genetic diversity of oil palm (Elaeis guineensis) populations in Nigeria. Their findings revealed significant genetic variation, which is essential for breeding programs aimed at improving oil yield and disease resistance, and correlates with the findings in this work using RAPD markers.

The chromosome characteristics reveal notable differences among the sampled palm species. The uniform chromosome counts of 32 in Coconut, Areca Palm, and Mexican Fan Palm signify their genetic stability within diploid populations. In contrast, the Oil Palm's diploid count of 16 suggests a unique evolutionary pathway, which may confer specific adaptive advantages in its native habitat. This observation aligns with the findings of Bezaweletaw23 and Judd et al.24, who noted that varying chromosome numbers in palm species can influence their reproductive biology and adaptability. The distinctive chromosome counts in Cycas, with its haploid set of 22, highlight its divergence within the palm family and support the notion of Cycadaceae as a separate evolutionary lineage, as discussed by Barrett et al.25. Phenotypic assessments demonstrate the rich diversity of morphological traits among the palm species. The variations in leaf arrangement, texture, and fruit characteristics reflect adaptations to their environments. For instance, the Coconut palm’s broad, fan-like leaves are well-suited to tropical climates, enhancing photosynthesis and water retention. This finding is corroborated by the works of Eiserhardt et al.26, who noted that phenotypic traits in palms are closely linked to their ecological adaptations.

The dendrogram analysis using OPA4 RAPD markers reveals important genetic relationships among the sampled species. The Coconut palm's distinct genetic divergence from the others, indicated by the longest branch length, supports earlier findings by Maira et al.27, who reported substantial genetic variation among palm species, and noted critical breeding strategies and conservation efforts. The clustering of Cycas and Oil Palm suggests a close genetic relationship, which could inform future breeding programs aimed at enhancing traits such as disease resistance and yield. Similarly, the close association between Areca Palm and African Fan Palm aligns with findings by Onstein et al.28, who identified genetic similarities among certain palm species, reinforcing the importance of genetic diversity in conservation planning29.

The genetic diversity analysis, as indicated by distinct DNA bands from the RAPD analysis, further supports the findings of genetic variation among the palm species. The presence of multiple distinct bands suggests a rich genetic background, which is essential for the resilience and adaptability of these species. This finding is consistent with the conclusions drawn by Jaradat30, who emphasized that genetic diversity is crucial for the long-term sustainability of palm species, especially in the context of environmental changes and agricultural pressures.

The findings from the taxonomic, chromosomal, phenotypic, and genetic analyses provide a robust framework for understanding the diversity and adaptability of palm species in the region.

A study by Khalilia et al.31 on date palms (Phoenix dactylifera) highlighted the variation in fruit characteristics across different cultivars, demonstrating how phenotypic traits can be used to select superior genotypes for commercial production.

Most challenges faced during the genetic and phenotypic assessments of species in the palm family lie in the lack of comprehensive information about their genetic diversity31. This gap in knowledge hampers efforts to improve species yield, disease resistance, and environmental adaptation. Without detailed genetic and phenotypic data, breeding programs cannot effectively select superior palm varieties, and conservation strategies may fail to protect genetically valuable populations. Additionally, the impact of environmental changes on palm species remains poorly understood, which is crucial for ensuring their sustainable cultivation and use.

Thus, there is a pressing need for extensive research to fill these gaps and provide valuable insights for agricultural improvement and conservation efforts. Based on the results of this finding, the implementation of conservation programs to protect diverse palm species, focusing on preserving their natural habitats and genetic diversity, is highly recommended. Also, Local farmers are encouraged to utilize the unique traits of different palm species for sustainable agricultural practices, enhancing crop yields while maintaining ecological balance. Continued research on the genetic and phenotypic diversity in palm species is recommended to better understand their adaptability and provide informed future breeding programs, especially as it concerns climate change mitigation. In terms of interspecific interactions on JOSTUM campus, palm species especially seem to host a higher epiphytic load, mirroring trends observed in more natural, biodiverse ecosystem settings. Human activity, such as campus landscaping, construction, and foot traffic, impacts epiphyte diversity32. On the JOSTUM campus, while epiphytes are present in various microhabitats, their distribution is often limited to less-disturbed areas like the Palm plantation site. This pattern is consistent with studies on urban biodiversity, where epiphyte richness tends to be lower in areas with frequent human disturbance33. While JOSTUM’s campus hosts a commendable diversity of epiphytes on palm trees, its proximity to anthropogenic activities may prevent it from achieving the epiphyte richness seen in undisturbed forests. In both urban and natural settings, epiphytes contribute significantly to ecological stability by offering habitats for invertebrates and small animals while aiding in nutrient cycling, as reported by Zotz34. The role of epiphytes is vast, as previous studies in other green spaces, where they enhance the microhabitat complexity and support biodiversity, have been reported Zhang et al.35. However, in high-diversity ecosystems like rainforests, epiphytes are reported to have contributed to a much broader ecological network, supporting specialized fauna and complex nutrient cycles36. Although JOSTUM’s epiphyte community may be of a small scale compared to larger epiphytic communities, it still plays a vital role in supporting the overall biodiversity on campus, thus enhancing ecological resilience in the existing plant communities.

CONCLUSION

The assessments of palm species in the University (JOSTUM) highlight the impressive diversity and environmental adaptability of species studied, revealing important information about their genetic, ecological, and morphological traits, and ability to thrive in various environments. The diverse morphological characteristics observed were well-suited to their habitats and played a significant role in local agricultural productivity. The study of interactions in palm species remains crucial for ensuring sustainable cultivation and use. This research reveals the evolutionary trends among members of the family Arecaceae and further illustrates their chromosomal variations, including ecological and interspecific interactions with other species, which are essential for breeding and conservation efforts. The diversity and ethnobotanical survey reveal that both the host tree plant in this case (Elaeis guineensis) and man are beneficiaries of the ecological contributions provided by the mutual coexistence of inventoried epiphytes, hence, the significant usage in local indigenous medicinal practice and in the treatment of various tropical ailments.

SIGNIFICANCE STATEMENT

This study identified Elaeis guineensis as the most dominant and species-rich member of Arecaceae, with Cocos nucifera exhibiting the highest diversity and Polystichum munitum being the dominant epiphyte. These findings could be beneficial for improving conservation strategies, biodiversity monitoring, and ecological restoration efforts involving palms and their associated species. This study will assist researchers in uncovering critical areas of species interaction and taxonomic relationships that have remained unexplored by many. Consequently, a new theory on palm-epiphyte ecological dynamics may be developed.

REFERENCES

- Yahaya, S.A., I.M. Koloche, L.O. Enabuere, A. Mijinyawa, B.M. Abdulkarim et al., 2023. Variability of some Nigerian date-palm (Phoenix dactylifera L) accessions as revealed by vegetative traits. Greener J. Agric. Sci., 13: 22-30.

- Alrashidi, A.H.M., A. Jamal, M.J. Alam, L. Gzara and N. Haddaji et al., 2023. Characterization of palm date varieties (Phoenix dactylifera L.) growing in Saudi Arabia: Phenotypic diversity estimated by fruit and seed traits. Notulae Botanicae Horti Agrobotanici Cluj-Napoca, 51.

- Acheampong, J.B., B. Effah, K. Antwi and E.W. Achana, 2021. Physical properties of palmyra palm wood for sustainable utilization as a structural material. Maderas Ciencia Tecnología, 24.

- Alqahtani, M.M., M.M. Saleh, K.M. Alwutayd, F.A. Safhi and S.A. Okasha et al., 2023. Performance and genotypic variability in diverse date palm (Phoenix dactylifera L.) cultivars for fruit characteristics. Genet. Resour. Crop E, 71: 1759-1772.

- Henderson, A., B. Fischer, A. Scariot, M.A.W. Pacheco and R. Pardini, 2000. Flowering phenology of a palm community in a central Amazon forest. Brittonia, 52: 149-159.

- Baker, W.J. and J. Dransfield, 2016. Beyond Genera palmarum: Progress and prospects in palm systematics. Bot. J. Linn. Soc., 182: 207-233.

- Salako, K.V., F. Moreira, R.C. Gbedomon, F. Tovissodé, A.E. Assogbadjo and R.L.G. Kakaï, 2018. Traditional knowledge and cultural importance of Borassus aethiopum Mart. in Benin: Interacting effects of socio-demographic attributes and multi-scale abundance. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed., 14.

- Oklo, A.D., I.A. Armstrong, O.M. Idoko, T.S. Iningev, A.A. Emmanuel and R.O. Oklo, 2021. Assessment of soil fertility in terms of essential nutrients contents in the lower Benue River Basin development authority project sites, Benue State, Nigeria. Open Access Lib. J., 8.

- Okpara, O.P. and O.I. Okogwu, 2024. Plant diversity at selected dumpsites in Abakaliki: Exploring species tolerance and carbon storage functions. J. Appl. Life Sci. Environ., 57: 673-700.

- Wehncke, E.V., X. López-Medellín, M. Wall and E. Ezcurra, 2013. Revealing an endemic herbivore-palm interaction in remote desert oases of Baja California. Am. J. Plant Sci., 4: 470-478.

- Edwards, K., C. Johnstone and C. Thompson, 2007. A simple and rapid method for the preparation of plant genomic DNA for PCR analysis. Nucleic Acids Res., 19: 1349-1349.

- Joshi, B.K., D. Joshi and S.K. Ghimire 2020. Genetic diversity in finger millet landraces revealed by RAPD and SSR markers. Nepal J. Biotechnol., 8: 1-11.

- Zhang, W. and Z. Sun, 2008. Random local neighbor joining: A new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol. Phylogenet. E, 47: 117-128.

- Joshi, C.P. and H.T. Nguyen, 1993. RAPD (random amplified polymorphic DNA) analysis based intervarietal genetic relationships among hexaploid wheats. Plant Sci., 93: 95-103.

- McPherson, E.G., Q. Xiao and E. Aguaron, 2013. A new approach to quantify and map carbon stored, sequestered and emissions avoided by urban forests. Landscape Urban Plann., 120: 70-84.

- Daa-Kpode U.A., D. Gustave, S.A. Edmond, V.S. Kolawolé, B.M. Farid and A. Kifouli, 2021. Ethnobotanical study of the coconut palm in the Coastal Zone of Benin. Int. J. Biodivers. Conserv., 13: 152-164.

- Eneji, I.S., O. Obinna and E.T. Azua, 2014. Sequestration and carbon storage potential of tropical forest reserve and tree species located within Benue State of Nigeria. J. Geosci. Environ. Prot., 2: 157-166.

- Lal, R., 2005. Forest soils and carbon sequestration. For. Ecol. Manage., 220: 242-258.

- Sedjo, R. and B. Sohngen, 2012. Carbon sequestration in forests and soils. Annu. Rev. Resour. Econ., 4: 127-144.

- Asiimwe, S., J. Namukobe, R. Byamukama and B. Imalingat, 2021. Ethnobotanical survey of medicinal plant species used by communities around Mabira and Mpanga Central Forest Reserves, Uganda. Trop. Med. Health.

- Smith, J.S.C., E.C.L. Chin, H. Shu, O.S. Smith and S.J. Wall et al., 1997. An evaluation of the utility of SSR loci as molecular markers in maize (Zea mays L.): Comparisons with data from RFLPS and pedigree. Theor. Appl. Genet., 95: 163-173.

- Panwar, P., M. Nath, V.K. Yadav and A. Kumar, 2010. Comparative evaluation of genetic diversity using RAPD, SSR and cytochrome P450 gene based markers with respect to calcium content in finger millet (Eleusine coracana L. Gaertn.). J. Genet., 89: 121-133.

- Bezaweletaw, K., 2011. Genetic diversity of finger millet [Eleusine coracana (L.) Gaertn] landraces characterized by random amplified polymorphic DNA analysis. Innovative Syst. Des. Eng., 2: 207-217.

- Judd, W.S., C.S. Campbell, E.A. Kellogg, P.F. Stevens and M.J. Donoghue, 2015. Plant Systematics: A Phylogenetic Approach. Sinauer, Sunderland, Massachusetts, USA, ISBN: 9781605353890, Pages: 565.

- Barrett, C.F., M.R. McKain, B.T. Sinn, X.J. Ge, Y. Zhang, A. Antonelli and C.D. Bacon, 2019. Ancient polyploidy and genome evolution in palms. Genome Biol. E, 11: 1501-1511.

- Eiserhardt, W.L., J.C. Svenning, W.D. Kissling and H. Balslev, 2011. Geographical ecology of the palms (Arecaceae): Determinants of diversity and distributions across spatial scales. Ann. Bot., 108: 1391-1416.

- Mair, L., O. Byers, C.M. Lees, D. Nguyen, J.P. Rodriguez, J. Smart and P.J.K. McGowan, 2020. Achieving international species conservation targets: Closing the gap between top-down and bottom-up approaches. Conserv. Soc., 19: 25-33.

- Onstein, R.E., W.J. Baker, T.L.P. Couvreur, S. Faurby, J.C. Svenning, W.D. Kissling, 2017. Frugivory-related traits promote speciation of tropical palms. Nat. Ecol. E, 1: 1903-1911.

- Shaari, M.A., S. Shahidan, S.I.S.M. Arbain, N. Ruslan, M.A. Hasli and N.M. Fadzli, 2024. Comparative analysis of oil content in Dura and Tenera palm fruit varieties. J. Sustainable Nat. Resour., 4: 57-61.

- Jaradat A.A., 2015. Biodiversity, Genetic Diversity, and Genetic Resources of Date Palm. In: Date Palm Genetic Resources and Utilization: Volume 1: Africa and the Americas, Al-Khayri, J., S. Jain and D. Johnson (Eds)., Springer, Dordrecht, Netherlands, ISBN: 978-94-017-9694-1, pp: 19-71.

- Khalilia, W.M., R. Abuamsha, N. Alqaddi and A. Omari, 2022. Phenotypic characterization of local date palm cultivars at Jericho in Palestinian Jordan Valley District. Indian J. Sci. Technol., 15: 989-1000.

- Callaway, R.M., K.O. Reinhart, G.W. Moore, D.J. Moore and S.C. Pennings, 2002. Epiphyte host preferences and host traits: Mechanisms for species-specific interactions. Oecologia, 132: 221-230.

- Song, L., W.Y. Liu and N.M. Nadkarni, 2012. Response of non-vascular epiphytes to simulated climate change in a montane moist evergreen broad-leaved forest in Southwest China. Biol. Conserv. 152: 127-135.

- Zotz, G., 2016. The Role of Vascular Epiphytes in the Ecosystem. In: Plants on Plants-The Biology of Vascular Epiphytes, Zotz, G. (Ed.), Springer, Cham, Switzerland, ISBN: 978-3-319-39237-0, pp: 229-243.

- Zhang, T., W. Liu, T. Hu, D. Tang, Y. Mo and Y. Wu, 2021. Divergent adaptation strategies of vascular facultative epiphytes to bark and soil habitats: Insights from stoichiometry. Forests, 12.

- Zotz, G., J.L. Andrade and H.J.R. Einzmann, 2023. CAM plants: Their importance in epiphyte communities and prospects with global change. Ann. Bot., 132: 685-698.

How to Cite this paper?

APA-7 Style

Okpara,

O.P., Okoh,

T., Kingsley,

M.T., Okanya,

A.O., Johnson,

E.O. (2025). Genetic Diversity and Inter-Specific Interactions in Family Arecaceae. Trends in Biological Sciences, 1(3), 227-248. https://doi.org/10.21124/tbs.2025.227.248

ACS Style

Okpara,

O.P.; Okoh,

T.; Kingsley,

M.T.; Okanya,

A.O.; Johnson,

E.O. Genetic Diversity and Inter-Specific Interactions in Family Arecaceae. Trends Biol. Sci 2025, 1, 227-248. https://doi.org/10.21124/tbs.2025.227.248

AMA Style

Okpara

OP, Okoh

T, Kingsley

MT, Okanya

AO, Johnson

EO. Genetic Diversity and Inter-Specific Interactions in Family Arecaceae. Trends in Biological Sciences. 2025; 1(3): 227-248. https://doi.org/10.21124/tbs.2025.227.248

Chicago/Turabian Style

Okpara, Onyinyechi, Priscilla, Thomas Okoh, Michael Tamaradoubra Kingsley, Alice Oheji Okanya, and Elizabeth Ogbene Johnson.

2025. "Genetic Diversity and Inter-Specific Interactions in Family Arecaceae" Trends in Biological Sciences 1, no. 3: 227-248. https://doi.org/10.21124/tbs.2025.227.248

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.