Role of Medicinal Plants in Asthma Treatment: Insights from Clinical Evidence

| Received 17 Apr, 2025 |

Accepted 29 Jun, 2025 |

Published 30 Jun, 2025 |

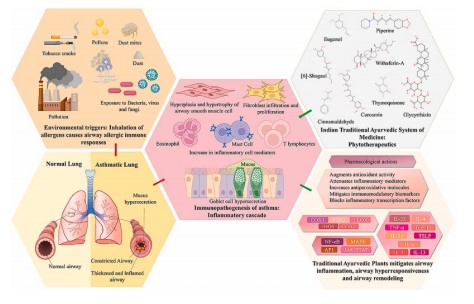

This review is about the effects of medicinal herbs in the treatment of asthma. Asthma is characterized by bronchospasm resulting in breathlessness (dyspnea) due to the high concentration of various inflammatory cells, which include eosinophils, mast cells, lymphocytes, and others, which cause constriction of the smooth muscle of the bronchus. Approximately 300 mL people suffer from asthma, in which they experience wheezing, shortness of breath, and coughing, particularly prevalent at night and early in the morning. Asthma has two types: Type 2 high and type 2 low. Both have different inflammatory mediators that cause inflammation of the mucous membrane. Many clinical trials show scientific evidence of the effects of phytomedicine in treating asthma, which are listed in this article.

| Copyright © 2025 Amar et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. |

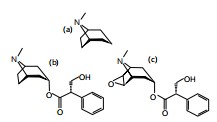

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Asthma is a complex, chronic inflammatory condition that causes airway narrowing along with variations in the amounts of mast cells, lymphoid cells, inflammatory mediators, white blood cells, and other cells involved in inflammatory conditions. It is thought that high concentrations of a specific type of immunoglobulin E, which binds to mastoid cells and other cell receptors connected to inflammation, are present in asthmatic patients. The interaction of the immunoglobulin E antibody with the antigen results in the release of prostaglandins, cytokines, and histamines, which set off a cascade of cellular events linked to inflammation. The soft tissues in the airways then compress as a result of these cellular responses, leading to constriction of the bronchi1-3.

Asthma is becoming more commonplace worldwide, with developed countries experiencing the highest prevalence. Asthma affects around three hundred million individuals worldwide, and by twenty-five, that figure is expected to increase to one hundred million people4,5. Since the 1970s, there has been an increase in the incidence, adverse effects, death rates, and financial burdens associated with asthma, particularly in children6.

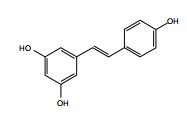

A man suffering from asthma can be treated with a plant. The literature revealed the medicinal values of plants for immune-stimulating, antihistaminic, and beneficial effects on inflammation7. According to Ayurveda, an anti-asthmatic medication should contain antikapha and anti-vata properties8. The damaging effects of excess oxygen species that react and unstable nitrogen species are neutralized by antioxidant medications, which decrease proinflammatory processes and lessen the severity of bronchoconstriction9.

Epidemiology: Statistics have indicated that the incidence of asthma is rising globally, especially in developing nations, and it is now thought that approximately 235 mL individuals throughout the world are affected by asthma10. The present level of asthma management in Latin American nations is significantly behind the objectives outlined by the most recent international11.

Since asthma usually develops early in childhood, most of the data currently available on its incidence in LA pertains to kids and teenagers12 as stated by the Global Research Study of Allergies and Asthmatic problem in Pediatrics (ISAAC), there are notable regional variationsin the incidence of signs of asthma across Latin American nations13. According to statistics from ISAAC’s phase 3 (2002-2003), children (6-7 years old) in Mexico had an average prevalence of current wheeze of 8.4%, whereas the nation of Costa Rica had an average prevalence of 37.6%14. According to Table 114, the percentage of cases of current cough among teenagers (13 to 14 years old) varied from 11.6% in Mexico to 30.8% in El Salvador.

ETIOLOGY OF ASTHMA

Asthma comes in a variety of phenotypes, each with its own symptoms, etiology, and pathophysiology. Risk elements for each subtype of asthma that have been discovered include immune-mediated, ecological, and biological triggers. While it is common, having breathing problems in the family does not guarantee that someone will have asthma.

TYPES OF INFLAMMATION IN ASTHMA

In accordance with the degree of inflammatory processes, asthma can be divided into a couple of groups: Type 2 (T2), which is severe, and T2 mild. The phenotypes of T2 lower asthma include paucigranular, TH9 elevated, and TH17 elevated (white blood cells).

Neutrophils infiltrate T2 low when the T helper 17 response cytokines, including interleukin-17, interleukin-21, or 22, are expressed more frequently15. The white blood cells are more common in phlegm and air passages in T2 high patients, and they generate more type 2 cytokines, including interleukin-4, interleukin-5, and interleukin-1316. Ecological and hereditary variables. A pro-inflammatory chain that is indicative of the second phase of severe inflammation is triggered by a response to an antigen (Table 1).

| Table 1: | Herbs thatare used in the treatment of asthma | |||

| Botanical name | Common name | Chemical constituent | Mechanism of action |

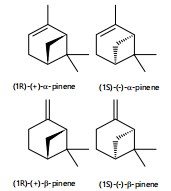

| Hyssopus officinalis L. | Zufakushk | Twenty percent of the compounds are β-pinene, 11.7% are α-phellandrene 7.6% are β-caryophyllene, a rate of 6% are Myrcene, 6.1% are Linalool, and 5.6% are limonene  |

Hyssopus officinal affects the levels of interleukin-4,-6, and -17 in asthmatic individuals. It has been shown that Hyssopus officinalis L. affects the levels of interleukin-4, -6, and -17 as well as interferon in asthmatic individuals. This has been listed in a Double-Blind, Randomised,Placebo- Controlled Study by Daneshfard et al.33 |

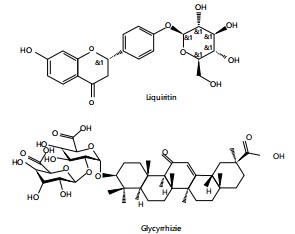

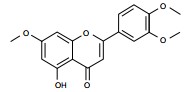

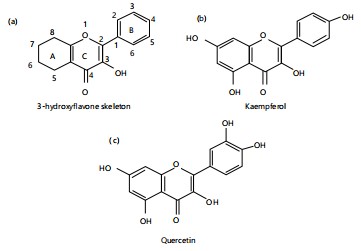

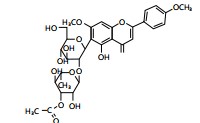

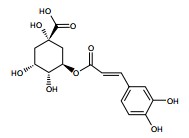

| Glycyrrhiza | Mulethi | Terpenoids and flavonoids. flavonoids: Liquiritin, liquiritigenin, isoliquiritigenin, 7,4 dihydroxyflavone  |

Reduce the production of Th2 cytokines and eotaxin. Eotaxin is involved in attracting eosinophils to asthmatic airways where antigen-induced inflammation is present. Eotaxin is mostly produced by lung fibroblasts. Licorice flavonoids inhibit eotaxin-1 secretion by human fetal lung fibroblasts in vitro34 |

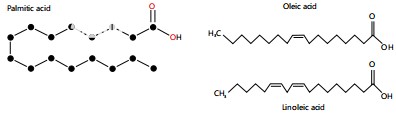

| Borago officinalis L. | (Gaozaban) flower | Fatty acids including palmitic, linoleic, stearic, and γlinolenic acids (13) |

Suppressing bronchial eosinophilic inflammation contain the highest amount of sterols with anti-oxidative and anti- inflammatory activities. The claim has been cited in a paper on Effect of Borago officinalis phase two, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial for moderately persistent asthma35 |

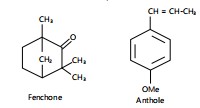

| Foeniculum vulgare | Badyan | Theophylline, methacholine, anethole, atropine |

The H1 histamine receptor inhibiting and adrenergic receptor stimulating properties of essential oils and plant extracts. The antinoceceptive effects partially mediated by histamine H1 and H2 receptors mentioned in study by Zendehdel et al.36 |

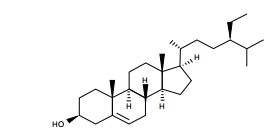

| Solanum nigrum | Mako | Antiasthmatic compound, β-sitosterol |

The most effective defense against clonidine- induced loss of mast cells was shown by a petroleum-based extract, which also significantly decreased the elevated neutrophil and number of leukocytes brought on by a milk allergy. In a study ether extract showed presence of antiasthmatic compound, β-sitosterol. The petroleum S. nigrum berry ether extract can suppress characteristics |

| Cordia dichotoma G. Forst. |

Sapistan | β-sitosterol and 3 ,5-dihydroxy4‘ ’methoxy flavanone |

Theophylline-induced calmness in bronchial smooth muscle.The methanolic extract of C. dichotoma exhibits anti-inflammatory properties in a rat paw oedema.The presence of phenolic phytoconstituents or plant flavonoid bark extract may be the cause of C. dichotoma’s anti-inflammatory properties38 |

| Vitis vinifera | Grapes | Polyphenols are antioxidant cyan pigments, ketones, the stilbenes (resveratrol), phenolic substances, proteins, lipids, vitamins C and A as well as minerals (magnesium, boron, iron), liquid, carbs, and polysaccharides are all found in fruit in substantial quantities  |

Gallic acid has been shown to suppress allergen-induced sensitivity responses in mice and inhibits the production of adrenaline and helper T cell subtypes, interleukin-4, interleukin-5, and interleukin-2 from human mast cell populations, according to studies conducted on several models for allergenic conditions. Gallic acid’s anti-allergic properties both in vivo and in vitro point to its to its potential use as a treatment for inflammatory allergic disorders39 |

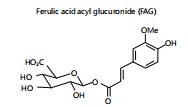

| Ficus carica L. | Anjeer | Polyphenols such as propranolol, 3O rutinoside, phenolic ingredients such as the ferulic 3-O-caffeoylquinic acid, and 5-O-psoralencaffeoylquinic acid28  |

Joshanda Anjeer: 3.5 grams of Joshanda’s Anjeer decoction is successful for dyspnea. Dry figs are an effective way to clear bronchial tubes of mucus. Beneficial food treatment for asthma. By removing the phlegm, it provides relief for the sufferer40 |

| Rosa damascene Mill | Gulab | Cyanidin, Kaempherol, |

It is also useful in asthma, bronchitis. A study’s conclusions demonstrated that rose oil causes bronchorelaxation in a way that is dependent on concentration. KV, KATP, and BKCa channel activity arelinked to the bronchodilation responses induced by rose oil. These findings imply that rose oil may be a helpful treatment for conditions like asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease that are linked to aberrant bronchoconstriction41 |

| Iris ensata Thunb | Baikhsosan | Protein content, nitrogenous compounds, cellulose, flavonoids, all glycosides, carbohydrates, tannins, C-glycosylflavones and oxides26  |

The plant’s root is utilized to treat breathing- related issues like respiratory infections, asthma, coughing, and pertussis. Abdul Haleem et al., (2015): Study was to standardise the herbal medication Iran. IRSA (Iris ensata) is a member of the Iridaceae family and is used to treat respiratory conditions like pneumonia, cough, asthma, and diphtheria42 |

| Althea officinalis | Khatmi | Pectins 11%, starch 25-35%, mono--, and disaccharide, saccharose 10%, mucilage |

Decreasing in Eosinophils in groups that received the drug. Lung Eosinophils were decreasing in the interstitial tissue. Effect of Althea in respiratory disorders has been reported in a study by Kayani et al.43 |

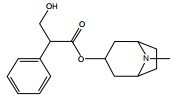

| Atropa belladona | Devils cherries | Atropine |

It has an ant-muscarinic effect that decreases smooth connective tissue activation and lowers the production of mucus by acting through the autonomic system of the body. It is utilized for the medicament of bronchial spasms in asthma, whooping cough and cold44. |

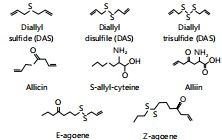

| Allium sativum | Garlic | Alliin, allicin, ajoenes, vinyldithiins, and flavonoids such as quercetin |

Lymphocyte counts, peribronchial pulmonary inflammatory cells, immunoglobulin 1 and plasma, mucous-producing cells of the goblet grade, and peribronchial and perivascular inflammation all showed a significant decline in the amount of asthmatic airway damage. The results indicate that garlic water fraction extracts have a definite anti-inflammatory impact on allergic asthma45 |

| Datura stramonium | Thorn apple | Atropine, or scopolamine, are examples of tropane alkaloids, which are tranquilizers that have a methylation atom of nitrogen  |

To affect these receptors on bronchial muscle fibers and submucosal glandular cells, the atropine and scopolamine inhibit them, especially their M2 receptors. The use of Daturastramonium for the treatment of asthma and its potential implications on the growth of babies46 |

Contact with allergens induces cells in the epithelium to produce Th2-stromal lymphopoietin, interleukin 25, and interleukin 33. These raise concerns, activate cells known as mast cells, T helper cell 2, and type 2 innate lymphoid cells. Dendritic cells are cells that digest the antigenic material and then deliver it to receptive T cells at the same time, which helps naïve T cells differentiate into T helper 2 cells.

5, and interleukin 1317,18. B lymphocytes produce more Immunoglobulin when exposed to interleukin 4 and interleukin 13, neutrophil metabolism is impacted via interleukin 5, and airway morphology could be influenced by interleukin 13. This intricate intercellular communication makes possible an atmosphere high in interleukin 4, interleukin

ENVIRONMENTAL FACTORS

Several risky environmental variables stand out as being well-replicated or having a meta-analysis of numerous studies to demonstrate their direct link with the development of asthma and morbidity in children. Atmospheric nicotine, particularly maternal tobacco use, is linked to a significant risk of wheezing, infections of the respiratory tract, and asthma severity and mortality19. Greater mortality from asthma is frequently related to poor air quality, which can result from vehicular pollution or high ozone levels, and there may be a link between poor air quality and asthmatic pathogenesis, which requires additional study by Perez and Coutinho20. Recent research has linked asthma among children to exposure to air contaminants, such as those from vehicle exhaust. This study reveals that airborne contaminants have an impact on the development of the condition and its manifestations in children21.

Viral infection: Roughly 80% of worsening is linked to infections caused by viruses of the respiratory tract, with rhinoviral contamination accounting for nearly two-thirds of cases22. When infected with the rhinovirus, asthmatic people experience substantially worse infections in their lower respiratory tracts than unaffected control participants23. Asthmatic participants also experienced greater signs of the lower airway tract, experienced worse lung health, and in an individual's diagnostic study involving rhinoviral sickness, there was more hypersensitivity in the airways compared to controls without bronchial asthma24.

Pathways of worsening symptoms caused by viruses: The processes that occur when a rhinovirus contamination exacerbation effects are still being studied. Although increased interleukin 6, interleukin 8, and interleukin 16 were translated and synthesized in messenger Ribonucleic Acid, exotoxin, IFN ginduced proteins 10 (IP-10), and rantes, as well as other cytokines that are Proinflammatory contamination causes inflammation and increases numbers of eosinophils, neutrophils, CD41 cells, CD81 cells, and mast cells. 10 For instance, IL-16 is a potent cell chemoattractant that further elicits the activation of macrophages and eosinophils. Eosinophils and lymphocytes are chemoattracted to RANTES, and their release, together with that associated with additional proinflammatory cytokines, can result in elevated airway responsiveness, inflammation, and the production of mucus25.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY OF ASTHMA

Asthma is a breathing-related inflammation disorder that can be incorrectly defined by hyperactive secretory glands, airway expansion caused by edema and mucus, and bronchoconstriction, which is the dilation of the airways in the lungs as a result of constricted, encompassing smooth muscle. Additionally, edema and swelling brought on by an immunological reaction to allergens contribute to bronchial inflammation-induced constriction. Bronchoconstriction: During a severe asthma episode, external factors such as airborne particles, smoke, or dirt cause inflammation in the airways. Breathing becomes challenging because the airways are constricted and overflowing with mucus. In its most basic form, asthma is brought on by an immunological reaction in the bronchial airways. Patients with asthma have “hypersensitive” airways to some triggers, also known as stimuli. The conventional categorization is classified as type I hypersensitivity. Various factors cause the bronchial tubes, or main breathing passages, to narrow and cause muscle spasms”. Swelling follows shortly, making the air passages even more constrictive and producing copious amounts of mucus, which results in spitting along with other difficulties with respiration. Around 50% of individuals experience asthma symptoms that either resolve on their own in two to 3 hrs or progress into an additional disease26.

SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS OF ASTHMA (DIQ-AL-NAFAS)

Everybody experiences Diq-al-Nafasa differently. Snoring, dyspnea, and sneezing are common complaints from individuals, especially at the beginning of the day and nighttime. Asthma diagnosis is significantly linked to wheezing and nighttime dyspnea.

The primary phases of Diq-al-Nafas symptoms are episodic and non-episodic, with pre-episodic constipation and bloating. A moderate cough is followed by difficulty breathing. A sudden episode happens, and the person suffers asphyxiation, anxiety, and feeble; the face gets red, a small amount of mucus emerges, and the entire body sweats. The patient seems to be in good health and not in any discomfort when they are relaxing27.

Vitamin D: There has been a rise in awareness within the past ten years that the sunshine vitamin plays in asthma. Several investigations have demonstrated that the severity of illness may be exacerbated by a serum vitamin D deficit. It has been established that immune-modulating and properties that reduce inflammation are possessed by sun exposure and increase the activity of the vitamin D Transporter. It was recently proposed that sunlight and vitamin D can inhibit adaptive as well as innate immune responses through this particular transmitter by affecting the proliferation of macrophages, dendritic cells, cell types T and B, and monocytes28.

Tobacco smoke exposure: It has been demonstrated that mothers who smoking raises the risk of developing asthma in children and coughing attacks during gestation. Furthermore, newer investigations have shown the impact of a parent’s nicotine throughout pregnancy on the formation of the fetus’s increases the baby’s risk of developing asthma.

A study that examined children whose parents smoked while they were expecting found that29 increased the baby’s risk of acquiring asthma by twice. If mothers kept smoking, maternal withdrawal may lower the risk of asthma. Pulmonary compliance and maximum inspiratory flow are both reduced following gestational intake of tobacco smoke, particularly narcotics30.

Air pollution: The development of cities and the subsequent contamination of the air have been related to both the incidence and exacerbation of asthma. One European study found that 14% of pediatric asthma attacks and 15% of all pediatric flare-ups were caused by pollution in the air.

Particulate matter, ozone, sulfur dioxide, and oxides of nitrogen have all been identified as the most likely reasons. Transport and manufacturing of energy that utilize petroleum and natural gas are the main sources of these contaminants. Certain hypotheses suggest that asthma is brought on by pollutants in the air through three mechanisms: damage from oxidation, which promotes airway reshaping; aeroallergen sensitivity; and increased inflammation, especially through the T helper cell 2 and T helper cell 17 channels. Furthermore, it has been shown that exposure to air pollution in children modifies the functioning of several alleles in the respiratory system31.

Genetic risk factors: Genetic variables have been demonstrated to be associated with asthma development, even if environmental variables are quite important. Studies looking at the familial inheritance of asthma have shown values ranging from 35 to 95%. The level of phenotypic variation within an individual caused by differences in genes among members of that group is known as genetic transmission. In a new investigation, the genetic makeup of over twenty-five thousand Swedish twins aged nine to twelve was determined to be 82%5. Along with the numerous outside variables that are believed to be connected to asthma, many genetic factors are additionally connected to the onset of the disease. Strategic cloning of eight asthma-related genes has been completed thus far: ADAM Metallopeptidase Domain 33, DPP10, PHF11, NPSR1, HLA-G, CYFIP2, IRAK3, and OPN332.

The therapeutic indication and relevant chemical composition has been addressed in Table 1. An information of dosage variations, toxicity hazards, and side effects will be given in this section. According to the literature review, all of the herbs listed have the potential to be therapeutically beneficial in the treatment of asthma.

The essential components of the herbs in the table have several functions. Its essential oil components have strong antiasthmatic effects and were effective in treating cough, loss of appetite, fungal infections, and spasmodic conditions. The cytotoxic activity, relaxing of the plasma membrane, and sedative effects are the other in vivo actions. Essential oils biological properties and fragrance point to their possible application as an antioxidant food additive and in other therapeutic products.

However, well-designed clinical trials that look at the characteristics of herbal extracts as described and potential negative reactions have not yet been explored. Further research is needed to determine whether biological differences in the research findings are caused by different plant material types, isolation techniques, chemotypes, collection times, and locations. Furthermore, more research is required to fully understand the molecular insights into different biological functions.

There are no stringent laws governing the use of natural remedies. This issue remains underappreciated and poorly understood47. Herbal remedies are not classified by the FDA or EFSA since they constitute a component of traditional medicine, which creates a false sense of safety.

CONCLUSION

The above studies mentioned in table 1 clearly demonstrated the therapeutic values of these phytopharmaceuticals for the cure of asthma. His is an edge in the current era of antibiotic resistance to have an alternate and safe therapeutic approach for acute and chronic patients suffering from asthma. However double blind clinical studies should be conducted to prove these medicaments as evidence based medicine.

SIGNIFICANCE STATEMENT

The prevalence of asthma is on the rise globally, particularly in developed nations. Patients are looking for alternative and complementary treatments for their conditions since current asthma phytotherapy offers insight as an alternate therapeutic regimen. In recent decades, several investigations on plants with antiallergic and antiasthmatic properties have been carried out by researchers. Nowadays, a lot of these plants are employed in medical settings, and researching their mode of action could lead to new concepts for making medications that work better. This review’s objective was to present a summary of research on plants and their active ingredients that have been shown to have antiasthmatic properties in experiments. To find and report the body of knowledge on herbs and their chemicals that may be useful in treating asthma, a literature search was carried out in Scopus, Springer Link, EMBASE, Science Direct, PubMed, Google Scholar, and Web of Science between 1986 and November, 2025. Future research must examine the bronchodilator and possible antiasthmatic effects of the listed plants, which have been demonstrated to have anti-inflammatory and antioxidative properties.

Clinical and experimental research has demonstrated that herbal medicine can alleviate asthma symptoms, and these chemicals could be a source for the creation of novel antiasthmatic medications. Furthermore, this review indicates that a large number of bioactive chemicals may be used as asthma treatments.

REFERENCES

- Iordanidou, M., S. Loukides and E. Paraskakis, 2017. Asthma phenotypes in children and stratified pharmacological treatment regimens. Expert Rev. Clin. Pharmacol., 10: 293-303.

- Corcoran, T.E., A.S. Huber, S.L. Hill, L.W. Locke and L. Weber et al., 2021. Mucociliary clearance differs in mild asthma by levels of type 2 inflammation. Chest, 160: 1604-1613.

- Lommatzsch, M., G.G. Brusselle, G.W. Canonica, D.J. Jackson, P. Nair, R. Buhl and J.C. Virchow, 2022. Disease-modifying anti-asthmatic drugs. Lancet, 399: 1664-1668.

- Kennedy, J.L., S. Pham and L. Borish, 2019. Rhinovirus and asthma exacerbations. Immunol. Allergy Clin. N. Am., 39: 335-344.

- Boulet, L.P., H.K. Reddel, E. Bateman, S. Pedersen, J.M. FitzGerald and P.M. O'Byrne, 2019. The Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA): 25 years later. Eur. Respir. J., 54.

- Enilari, O. and S. Sinha, 2019. The global impact of asthma in adult populations. Ann. Global Health, 85.

- Braman, S.S., 2006. The global burden of asthma. Chest, 130: 4S-12S.

- Incorvaia, C., S. Masieri, C. Cavaliere, E. Makri, B. Sposato and F. Frati, 2018. Asthma associated to rhinitis. J. Biol. Regulators Homeostatic Agents, 32: 67-71.

- Iyengar, M.A., K.M. Jambaiah, M.S. Kamath and G.M. Rao, 1994. Studies on an antiastham kada: A proprietary herbal combination. Part I: Clinical study. Indian Drugs, 31: 183-186.

- Tsai, M.K., Y.C. Lin, M.Y. Huang, M.S. Lee and C.H. Kuo et al., 2018. The effects of asthma medications on reactive oxygen species production in human monocytes. J. Asthma, 55: 345-353.

- Asher, M.I., L. García-Marcos, N.E. Pearce and D.P. Strachan, 2020. Trends in worldwide asthma prevalence. Eur. Respir. J., 56.

- Dharmage, S.C., J.L. Perret and A. Custovic, 2019. Epidemiology of asthma in children and adults. Front. Pediatr., 7.

- García-Marcos, L., M.I. Asher, N. Pearce, E. Ellwood and K. Bissell et al., 2022. The burden of asthma, hay fever and eczema in children in 25 countries: GAN Phase I study. Eur. Respir. J., 60.

- Mallol, J., L. Garcia-Marcos, D. Sole, P. Brand and EISL Study Group, 2010. International prevalence of recurrent wheezing during the first year of life: Variability, treatment patterns and use of health resources. Thorax, 65: 1004-1009.

- Halwani, R., A. Sultana, A. Vazquez-Tello, A. Jamhawi, A.A. Al-Masri and S. Al-Muhsen, 2017. Th-17 regulatory cytokines IL-21, IL-23 and IL-6 enhance neutrophil production of IL-17 cytokines during asthma. J. Asthma, 54: 893-904.

- Zhao, S., Y. Jiang, X. Yang, D. Guo and Y. Wang et al., 2017. Lipopolysaccharides promote a shift from Th2-derived airway eosinophilic inflammation to Th17-derived neutrophilic inflammation in an ovalbumin-sensitized murine asthma model. J. Asthma, 54: 447-455.

- McEvoy, C.T. and E.R. Spindel, 2017. Pulmonary effects of maternal smoking on the fetus and child: Effects on lung development, respiratory morbidities, and life long lung health. Paediatr. Respir. Rev., 21: 27-33.

- Vardoulakis, S. and N. Osborne, 2017. Air pollution and asthma. Arch. Dis. Childhood, 103: 813-814.

- Mallol, J., D. Solé, M. Baeza-Bacab, V. Aguirre-Camposano, M. Soto-Quiros, C. Baena-Cagnani and Latin American ISAAC Group, 2010. Regional variation in asthma symptom prevalence in Latin American children. J. Asthma, 47: 644-650.

- Perez, M.F. and M.T. Coutinho, 2021. An overview of health disparities in asthma. Yale J. Biol. Med., 94: 497-507.

- Szefler, S.J., D.A. Fitzgerald, Y. Adachi, I.J. Doull and G.B. Fischer et al., 2020. A worldwide charter for all children with asthma. Pediatr. Pulmonol., 55: 1282-1292.

- Liu, W., J. Cai, C. Huang and J. Chang, 2020. Residence proximity to traffic-related facilities is associated with childhood asthma and rhinitis in Shandong, China. Environ. Int., 143.

- Jartti, T. and J.E. Gern, 2017. Role of viral infections in the development and exacerbation of asthma in children. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol., 140: 895-906.

- Bjerregaard, A., I.A. Laing, N. Poulsen, V. Backer and A. Sverrild et al., 2017. Characteristics associated with clinical severity and inflammatory phenotype of naturally occurring virus-induced exacerbations of asthma in adults. Respir. Med., 123: 34-41.

- Lopes, G.P., Í.P.S. Amorim, B. de Oliveira de Melo, C.E.C. Maramaldo and M.R.Q. Bomfim et al., 2020. Identification and seasonality of rhinovirus and respiratory syncytial virus in asthmatic children in tropical climate. Biosci. Rep., 40.

- Sinyor, B. and L.C. Perez, 2023. Pathophysiology of Asthma. StatPearls Publishing, Tampa, Florida, United States.

- Ahmed, N., M. Zakir, M.A. Alam, G. Javed and A. Minhajuddin, 2022. Management of asthma (ḌĪQ Al-Nafas) in Unani system of medicine. Int. J. Health Sci., 6: 13036-13054.

- Wegienka, G., E. Zoratti and C.C. Johnson, 2015. The role of the early-life environment in the development of allergic disease. Immunol. Allergy Clin. N. Am., 35: 1-17.

- Harju, M., L. Keski-Nisula, L. Georgiadis and S. Heinonen, 2016. Parental smoking and cessation during pregnancy and the risk of childhood asthma. BMC Public Health, 16.

- Willis-Owen, S.A.G., W.O.C. Cookson and M.F. Moffatt, 2018. The genetics and genomics of asthma. Annu. Rev. Genom. Hum. Genet., 19: 223-246.

- Maspero, J., Y. Adir, M. Al-Ahmad, C.A. Celis-Preciado and F.D. Colodenco et al., 2022. Type 2 inflammation in asthma and other airway diseases. ERJ Open Res., 8.

- Chipps, B.E., B. Lanier, H. Milgrom, A. Deschildre and G. Hedlin et al., 2017. Omalizumab in children with uncontrolled allergic asthma: Review of clinical trial and real-world experience. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol., 139: 1431-1444.

- Daneshfard, B., F. Amini, A.M. Jaladat, B. Momeni, A. Abdolahinia, A. Hosseinkhani and L. Hosseini, 2024. Effect of hyssop (Hyssopus officinalis) syrup on mild to moderate asthma: A randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Tanaffos, 23: 146-155.

- Jayaprakasam, B., S. Doddaga, R. Wang, D. Holmes, J. Goldfarb and X.M. Li, 2009. Licorice flavonoids inhibit eotaxin-1 secretion by human fetal lung fibroblasts in vitro. J. Agric. Food Chem., 57: 820-825.

- Mirsadraee, M., S.K. Moghaddam, P. Saeedi and S. Ghaffar, 2016. Effect of Borago officinalis extract on moderate persistent asthma: A phase two randomized, double blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Tanaffos, 15: 168-174.

- Zendehdel, M., M. Taati, M. Amoozad and F. Hamidi, 2012. Antinociceptive effect of the aqueous extract obtained from Foeniculum vulgare in mice: The role of histamine H1 and H2 receptors. Iran. J. Vet. Res., 13: 100-106.

- Nirmal, S.A., A.P. Patel, S.B. Bhawar and S.R. Pattan, 2012. Antihistaminic and antiallergic actions of extracts of Solanum nigrum berries: Possible role in the treatment of asthma. J. Ethnopharmacol., 142: 91-97.

- Hussain, N., B.B. Kakoti, M. Rudrapal, Zubaidur Rahman, Mokinur Rahman, D. Chutia and K.K. Sarwa, 2020. Anti-inflammatory and antioxidant activities of Cordia dichotoma Forst. Biomed. Pharmacol. J., 13: 2093-2099.

- Kim, S.H., C.D. Jun, K. Suk, B.J. Choi and H. Lim et al., 2006. Gallic acid inhibits histamine release and pro-inflammatory cytokine production in mast cells. Toxicol. Sci., 91: 123-131.

- Rahmani, A.H. and Y.H. Aldebasi, 2017. Ficus carica and its constituents role in management of diseases. Asian J. Pharm. Clin. Res., 10: 49-53.

- Demirel, S., 2022. Rosa damascena Miller essential oil relaxes rat trachea via KV channels, KATP channels, and BKCa channels. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediators, 163.

- Abdul Haleem, Abdul Latif, Abdur Rauf, N. Siddiqui and Sumbul Rehman, 2015. Physicochemical and phytochemical standardization of IRSA (Iris ensata Thunb.). Int. J. Res. Dev. Pharm. Life Sci., 4: 1498-1505.

- Kayani, S., M. Ahmad, M. Zafar, S. Sultana and M.P.Z. Khan et al., 2014. Ethnobotanical uses of medicinal plants for respiratory disorders among the inhabitants of Gallies-Abbottabad, Northern Pakistan. J. Ethnopharmacol., 156: 47-60.

- Rubika, J., 2014. Atropha belladonna and its medicinal uses-A short review. Res. J. Pharm. Tech., 7: 926-930.

- Hsieh, C.C., K.F. Liu, P.C. Liu, Y.T. Ho, W.S. Li, W.H. Peng and J.C. Tsai, 2019. Comparing the protection imparted by different fraction extracts of garlic (Allium sativum L.) against der p-induced allergic airway inflammation in mice. Int. J. Mol. Sci., 20.

- Pretorius, E. and J. Marx, 2006. Datura stramonium in asthma treatment and possible effects on prenatal development. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol., 21: 331-337.

- Burkhard, P.R., K. Burkhardt, C.A. Haenggeli, T. Landis, 2002. Plant-induced seizures: Reappearance of an old problem. J. Neurol., 246: 667-670.

How to Cite this paper?

APA-7 Style

Amar,

A., Nazar,

H., Fazal,

A., ,

M.A. (2025). Role of Medicinal Plants in Asthma Treatment: Insights from Clinical Evidence. Trends in Biological Sciences, 1(1), 46-59. https://doi.org/10.21124/tbs.2025.46.59

ACS Style

Amar,

A.; Nazar,

H.; Fazal,

A.; ,

M.A. Role of Medicinal Plants in Asthma Treatment: Insights from Clinical Evidence. Trends Biol. Sci 2025, 1, 46-59. https://doi.org/10.21124/tbs.2025.46.59

AMA Style

Amar

A, Nazar

H, Fazal

A,

MA. Role of Medicinal Plants in Asthma Treatment: Insights from Clinical Evidence. Trends in Biological Sciences. 2025; 1(1): 46-59. https://doi.org/10.21124/tbs.2025.46.59

Chicago/Turabian Style

Amar, Azalfa, Halima Nazar, Areeba Fazal, and Misbah Ahmed .

2025. "Role of Medicinal Plants in Asthma Treatment: Insights from Clinical Evidence" Trends in Biological Sciences 1, no. 1: 46-59. https://doi.org/10.21124/tbs.2025.46.59

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.