Bioactive Compounds in Lamiaceae, Ranunculaceae, and Zingiberaceae: A Review of Healing Potential

| Received 28 Apr, 2025 |

Accepted 16 Jun, 2025 |

Published 30 Jun, 2025 |

The phytochemical analysis of medicinal plants has unveiled a remarkable variety of bioactive compounds that hold significant promise in therapeutic applications. This review highlights the three families of Angiosperms, i.e., Lamiaceae, Ranunculaceae and Zingiberaceae. Each of these plant families is distinguished by its rich reservoir of secondary metabolites, which include essential oils, flavonoids, alkaloids, and terpenoids, all of which are known for their diverse health benefits. Lamiaceae, including mint, sage, and basil, is rich in phenolic compounds and essential oils with strong antimicrobial and antioxidant properties. Ranunculaceae, home to buttercups and aconite, produces cardiac glycosides and alkaloids, many of which show anti-cancer and analgesic potential. Zingiberaceae, featuring ginger and turmeric, is abundant in gingerols and curcuminoids, valued for their anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects. Ongoing research into these plant families is continually revealing new compounds and validating their traditional medicinal applications, paving the way for the development of innovative pharmaceutical agents and nutraceuticals that could greatly enhance human health. The exploration of these biodiverse families not only enriches our understanding of herbal medicine but also opens doors to new treatments and wellness solutions.

| Copyright © 2025 Sharma et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. |

INTRODUCTION

Phytochemicals, derived from the Greek term “Phyto”, which means plant, are biologically active and naturally occurring chemical compounds found in plants. These substances provide health advantages over and beyond those of macronutrients and micronutrients. In addition to providing protection from illnesses and harm, they can enhance the colour, flavour, and aroma of plants. In essence, phytochemicals are responsible for enhancing plant resilience against environmental challenges such as stress, pollution, drought, ultraviolet exposure, and pathogenic threats1. Recent studies indicate that their incorporation into the diet can significantly contribute to human health. About 150 of the more than 4,000 phytochemicals that have been catalogued and categorized based on their chemical, physical, and defensive properties have received in-depth research2. A wide variety of dietary phytochemicals can be found in vegetables, fruits, legumes, nuts, herbs, fungi, whole grains, seeds, and spices. Common sources include whole wheat bread, cabbage, broccoli, onions, carrots, garlic, grapes, tomatoes, legumes, raspberries, cherries, beans, strawberries, and soy products. These substances build up in the plant's fruits, leaves, flowers, stems, roots, and seeds, with the outer layers of plant tissues usually containing the majority of the pigment molecules3. Concentration levels vary significantly among different plant varieties and are influenced by factors such as processing, cooking, and growing conditions. Although phytochemicals are available as supplements, there isn't much proof to back up the claim that they offer the same health advantages as those obtained from food. These substances, which are categorized as secondary plant metabolites, have a wide range of biological characteristics, such as anticancer, antioxidant, antimicrobial, detoxification enzyme, immune system stimulation, decreased platelet aggregation, and hormone metabolism modulation4. Although over a thousand phytochemicals are known, many remain unidentified. It is well established that plants produce these chemicals for self-defence, and ongoing research demonstrates that many phytochemicals may also confer protective benefits to humans against various diseases.

Phytochemicals, although not classified as essential nutrients necessary for sustaining human life, possess a variety of significant properties that can help prevent or combat various common diseases. These naturally occurring compounds have garnered considerable attention due to their potential roles in disease prevention and treatment, leading researchers to conduct numerous studies to uncover the beneficial health effects associated with phytochemicals5.

Although individual studies have explored the pharmacological effects of specific species within these families, a consolidated comparison of their bioactive constituents and therapeutic potential remains limited. This review aims to bridge that gap by systematically examining the major classes of bioactive compounds present in representative species from Lamiaceae, Ranunculaceae, and Zingiberaceae, and by evaluating their documented healing properties.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A comprehensive collection of relevant literature has been gathered from esteemed platforms such as PubMed, NCBI, Google Scholar, Web of Science, and Scopus, all of which are readily accessible online. This report has been formulated using a qualitative research methodology, which involved a thorough examination and analysis of the selected sources to delve into various concepts, synthesize information, and interpret the resulting insights. The main body of the report is centered around a documentary analysis, articulated through detailed narrative descriptions that capture the essence of the findings.

RESULTS

Journey of medicinal plant research: Before examining contemporary advancements, it is helpful to consider historical patterns and the impact of research on the phytochemistry of medicinal plants worldwide. Following centuries of traditional use of herbal remedies, the early 19th century witnessed the first isolation of active compounds known as alkaloids, such as strychnine, morphine, and quinine, signifying a new chapter in the application of medicinal plants and the inception of contemporary medicinal plant research. After 1945, the emphasis shifted from plant-based medications to synthetic pharmaceutical chemistry and microbial fermentation. Plant metabolites were primarily studied from a phytochemical and chemotaxonomic perspective during this period. However, in the past decade, there has been a consistent rise in interest in drugs of plant and, perhaps, animal origin. The usage of medicinal plants in Western Europe has nearly doubled during this timeframe. Factors contributing to this resurgence include ecological awareness, the effectiveness of various phytopharmaceuticals like ginkgo, garlic, and valerian, as well as the increased interest of large pharmaceutical corporations in higher medicinal plants as potential sources of new lead chemicals. As pharmacology and chemical science advanced, physicians began to remove chemicals from therapeutic plants6. For example, the French

chemists Peletier and Caventou isolated quinine from Cinchona in 1920. Hoffmann, a German chemist, extracted aspirin from willow bark in the mid-1800s. Pure chemicals that were more potent and easier for medical professionals to prescribe and deliver gradually began to replace plant-based prescriptions as a result of the discovery and isolation of active components in medicinal plants4. Phytomedicine nearly faded away during the early 21st century due to the prevalence of “More powerful and potent synthetic drugs”. However, given the many negative consequences of modern treatments, the importance of medicinal plants is being reinforced because some of them have shown effectiveness comparable to synthetic drugs with fewer or no side effects and contraindications. Research has shown that although the effects of natural remedies may appear to manifest more slowly, the results can be more favorable in the long term, particularly for chronic conditions7.

Biological activities of phytochemicals: To ascertain their efficacy and understand the processes behind their activities, the phytochemicals present in plants that promote health and prevent illness have been extensively studied. Research has involved the identification and extraction of these chemical components, as well as the demonstration of their biological effectiveness through both in vitro and in vivo experiments with animals, alongside epidemiological and clinical case-control studies in humans8. These studies’ conclusions suggest that phytochemicals may reduce the risk of coronary heart disease by preventing LDL (low-density lipoprotein) cholesterol from oxidizing, reducing cholesterol synthesis or absorption, regulating blood pressure and clotting, and improving artery elasticity. Additionally, phytochemicals may aid in the detoxification of toxins that cause cancer9. They appear to counteract free radicals, inhibit carcinogen-activating enzymes, and activate carcinogen-detoxifying enzymes. According to information gathered by Harichandan et al.4 genistein prevents the development of new blood vessels that are necessary for tumor growth and metastasis. Only a few phytochemicals' physiological characteristics are well known, and further study has focused on how they may be used to prevent or cure cardiovascular and cancer conditions. Additionally, phytochemicals have been recommended for the treatment and prevention of macular degeneration, diabetes, and high blood pressure6. While phytochemicals are categorized based on their functions, a single compound may possess multiple biological roles, acting both as an antibacterial and an antioxidant agent. Bioactive phytochemicals that prevent disease and are found in plants are presented in Table 1.

Habitats of Lamiaceae, Ranunculaceae and Zingiberaceae: The Lamiaceae, Ranunculaceae, and Zingiberaceae families represent three distinct lineages within the angiosperms, each exhibiting unique morphological and ecological traits that set them apart. Lamiaceae, commonly known as the mint family, is renowned for its distinctive square stems and opposite leaf arrangement, which gives rise to a robust and aromatic foliage. The flowers of this family are bilabiate, featuring fused petals that create a characteristic two-lipped appearance.

| Table 1: | Bioactive phytochemicals found in medicinal plants10 | |||

| Classification | Main groups of compounds | Biological function |

| NSA (non-starch polysaccharides) | Cellulose, mucilage, hemicellulose, pectin, gums, lignin |

Water-holding capacity, bile acid and toxin binding, and delayed nutrition absorption |

| Antifungal and antibacterial | Terpenoids, phenolics, alkaloids | Inhibitors of micro-organisms (MOs), reduce the risk of fungal infection |

| Antioxidants | Flavonoids, ascorbic acid, polyphenolic compounds, tocopherols, carotenoids |

Lipid peroxidation inhibition and oxygen free radical quenching |

| Anticancer | Carotenoids, curcumin, flavonoids polyphenols |

Anti-metastatic action, tumor inhibitors, and lung cancer development inhibition |

| Detoxifying agents | Reductive acids, retinoids, phenols, aromatic isothiocyanates, indoles, tocopherols, flavones, coumarins, cyanates, phytosterols, carotenoids |

Procarcinogen activation inhibitors, carcinogen drug binding inducers, and tumorigenesis inhibitors |

| Other | Alkaloids, volatile flavour compounds, terpenoids, biogenic amines |

Antioxidants, neuropharmacological agents, and cancer chemoprevention |

|

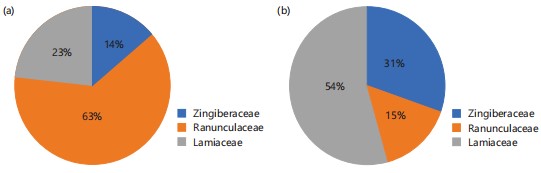

Many members of the Lamiaceae thrive in temperate climates and are often rich in essential oils, contributing to their popularity in culinary and medicinal applications. The family includes a variety of herbs and shrubs, enhancing biodiversity in the ecosystems they inhabit11. In contrast, the Ranunculaceae, or buttercup family, is characterized by its typically radially symmetrical flowers that display a stunning array of colors. This family is known for its numerous stamens and separate carpels, which contribute to its reproductive diversity. Most Ranunculaceae members are herbaceous plants, often found in cooler regions, and they play essential roles in their habitats, providing food and shelter for various wildlife. Their flowers, sprawling across meadows and woodlands, add splashes of vibrant color to the landscape12. On the other hand, Zingiberaceae, the ginger family, is primarily found in tropical environments. This family includes rhizomatous herbs that boast large, lush leaves arranged in a two-ranked formation, creating an impressive visual display. The flowers are particularly noteworthy; they often feature a strikingly showy and asymmetrical structure, with fewer, reduced stamens and a labellum formed from modified staminodes. These adaptations not only enhance their aesthetic appeal but also attract specific pollinators, ensuring successful reproduction in their warm, humid habitats13. While Lamiaceae and Ranunculaceae are considered more closely related as part of the eudicot lineage, Zingiberaceae aligns with the monocots, highlighting fundamental differences in their evolutionary development and structural makeup. The variations among these families illustrate the incredible diversity and adaptability of flowering plants within different ecological niches. Figure 1(a-b) shows the Distribution of Genera and Species in Zingiberaceae, Ranunculaceae, and Lamiaceae.

Medicinal uses of Lamiaceae, Ranunculaceae and Zingiberaceae: Ethnomedicinal practices have a rich history of harnessing the therapeutic potential of plants belonging to the Lamiaceae, Ranunculaceae, and Zingiberaceae families. The Lamiaceae family, often referred to as the mint family, encompasses a variety of aromatic herbs, including lavender, rosemary, and sage. These herbs are celebrated not only for their delightful fragrances but also for their remarkable health benefits. Traditionally, they have been used for their antimicrobial properties to ward off infections, their anti-inflammatory effects to soothe aches and pains, and their calming qualities to promote relaxation and well-being4.

In contrast, the Ranunculaceae family, commonly known as the buttercup family, features plants like black cohosh and goldenseal. These species have been integral to traditional medicinal practices, particularly for their efficacy in addressing menstrual disorders and digestive issues. The natural compounds found in these plants have been historically valued for their ability to balance hormonal fluctuations and alleviate gastrointestinal discomfort12.

Meanwhile, the Zingiberaceae family, which includes well-known spices like ginger and turmeric, is admired for its extraordinary anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties. These vibrant rhizomes are widely used in various cultures not just for enhancing culinary dishes but also for their health benefits.

Ginger is frequently recognized for its ability to alleviate digestive discomfort and nausea, while turmeric is renowned for its potential to reduce pain and bolster immune response, owing to its active compound, curcumin14.

Together, these plant families have profoundly influenced traditional medicine across the globe, laying the groundwork for numerous remedies that persist today. Their rich history continues to inspire modern pharmacological research and novel drug discovery as scientists delve into nature’s vast pharmacopeia.

Difference in phytochemicals of Lamiaceae, Ranunculaceae and Zingiberaceae: The Lamiaceae, Ranunculaceae, and Zingiberaceae families exhibit distinct phytochemical profiles, each characterized by unique compounds that contribute to their medicinal properties and ecological roles.

The Lamiaceae family is distinguished by its rich composition of essential oils, which are laden with fragrant monoterpenes and sesquiterpenes. These compounds not only impart a delightful aroma but also contribute to the plants’ potential antimicrobial properties. Among its abundant phytochemicals, phenolic compounds play a significant role, with rosmarinic acid standing out for its powerful anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects15. Additionally, this family is home to a diverse array of flavonoids, including flavones and flavanones. These naturally occurring compounds may enhance the plants’ antioxidant properties and offer promising anti-cancer benefits. Notably, the Lamiaceae family produces unique diterpenes, such as carnosic acid and carnosol, which have garnered attention for their neuroprotective and anti-inflammatory capabilities. Furthermore, triterpenes like ursolic and oleanolic acids found in these plants have shown potential benefits in managing diabetes and preventing cancer. Overall, the Lamiaceae family is a treasure trove of bioactive compounds that contribute to both their traditional uses and modern health applications16.

The Ranunculaceae family is notable for its diverse array of alkaloids, particularly isoquinoline and diterpene alkaloids. These compounds often play a crucial role in the family’s distinctive toxicity, which can serve both as a defense mechanism against herbivores and as potential agents for medicinal purposes. One of the key components within this family is ranunculin, a toxic glycoside that acts as a chemical deterrent, protecting the plants from being consumed by animals12. Additionally, members of the Ranunculaceae family produce saponins, especially triterpene saponins, which are known for their hemolytic properties-the ability to break down red blood cells-and their anti-inflammatory effects. The presence of flavonoids, such as flavonols and anthocyanins, further enriches these plants, contributing not only to their vibrant pigmentation but also to their potential health benefits for humans17. While some essential oils can be found within this family, they are less common when compared to those from the Lamiaceae family. The compositions of these essential oils can vary significantly across different genera, adding another layer of complexity to the fascinating chemistry of Ranunculaceae.

The Zingiberaceae family, notable for its rich diversity of phytochemical compounds, stands out primarily due to its high concentrations of phenolic compounds, especially gingerols and shogaols. These compounds not only impart a distinct pungent flavour to the plants but also are associated with potential anti-inflammatory benefits, making them a staple in both culinary and medicinal applications18. Additionally, the family is characterized by the presence of sesquiterpenes, such as zingiberene and curcumin, which contribute to the signature aromas of various species. These aromatic compounds are believed to possess medicinal properties, further enhancing the family’s utility in traditional practices. Among the unique compounds produced by the Zingiberaceae family are diarylheptanoids, with curcumin being particularly notable. Curcumin is recognized for its powerful antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects, adding to the health benefits associated with turmeric, a well-known member of this family. Flavonoids, including kaempferol and quercetin derivatives, are also present, contributing to the family’s overall antioxidant capabilities and potential anti-cancer properties. These compounds demonstrate the family’s role in health promotion and disease prevention. The essential oils found in the Zingiberaceae family, rich in monoterpenes and sesquiterpenes, are largely responsible for the distinct fragrances that many of these plants are known for19. These essential oils not only serve aromatic purposes but also exhibit potential antimicrobial activities, showcasing another layer of their ecological significance. The diverse chemical profiles found within the Zingiberaceae family illustrate the various evolutionary adaptations that these plants have developed in response to their ecological environments. These adaptations are vital not only for their medicinal properties and culinary applications but also for their ecological interactions with plants and animals20.

For example, members of the Lamiaceae family benefit from their essential oils, making them popular choices for culinary uses and aromatherapy. In contrast, the Ranunculaceae family, while rich in alkaloids with promising pharmaceutical potential, also presents challenges due to the toxicity of some of its members. The Zingiberaceae family’s phenolic compounds and sesquiterpenes have secured the popularity of plants like ginger and turmeric in both cooking and natural medicine, highlighting their importance across various domains. The complete summary of the collected information is presented in Table 2.

DISCUSSION

The phytochemical exploration of medicinal plants belonging to the Lamiaceae, Ranunculaceae, and Zingiberaceae families uncovers a remarkable tapestry of bioactive compounds, each possessing significant therapeutic potential. Each botanical family showcases a distinct phytochemical composition, enriching not only their medicinal benefits but also their ecological significance. The Lamiaceae family, commonly known as the mint family, is renowned for its abundant essential oils, an array of phenolic compounds, and vibrant flavonoids. These elements contribute to an impressive suite of health benefits, enhancing the family’s antimicrobial, antioxidant, and anti-inflammatory qualities. The aroma of herbs like basil, mint, and rosemary is indicative of their essential oils, which have been appreciated for centuries in both culinary and medicinal applications. In contrast, the Ranunculaceae family, often referred to as the buttercup family, is distinguished by its diverse range of alkaloids. Among these are isoquinoline and diterpene alkaloids, alongside saponins and flavonoids. These compounds not only play a pivotal role in plant defense against herbivores and pathogens but also hold promise for potential medicinal uses, offering a wealth of possibilities in therapeutic applications. Zingiberaceae family, which includes well-known plants like ginger and turmeric, these species are particularly remarkable for their high concentrations of phenolic compounds, notably gingerols and shogaols. These compounds not only impart unique flavours but are also linked to various health benefits, including anti-inflammatory properties and digestive aids. Additionally, the presence of sesquiterpenes and diarylheptanoids further enhances their medicinal profile.

Across cultures and civilizations, these plant families have significantly shaped traditional medicine, laying the groundwork for countless remedies that persist in modern usage. Their complex phytochemical profiles not only underscore their therapeutic potential but also highlight their essential roles in ecological dynamics and adaptations. Current research into these fascinating plant families continues to unveil a plethora of new compounds and validate the historical use of these plants in traditional medicine. This ongoing inquiry not only opens pathways for the development of innovative pharmaceuticals and nutraceuticals but also greatly enhances the potential for improving human health. As our understanding of these biodiverse families deepens, it becomes increasingly evident that the intersection of ancient wisdom and contemporary scientific exploration holds remarkable promise for the future of medicine. The continued investigation into the mechanisms of action of these phytochemicals and the quest to create safe, effective therapeutic applications from these natural compounds is vital in harnessing their full potential for enhancing wellness and healing.

| Table 2: | Phytochemical and medicinal properties of selected plants | |||

| S. No. | Plant name | Phytochemicals present | Medicinal properties | References |

| Lamiaceae | ||||

| 1 | Salvia officinalis L. (Sage) | α-pinene, bornyl acetate, limonene, camphene, cineole, camphor, humulene, thujone |

Anticancer, antinociceptive, anti-inflammatory, antimutagenic, antioxidant, hypoglycemic, antidementia, antimicrobial, hypolipidemic effects |

Ghorbani and Esmaeilizadeh21 |

| 2 | Mentha piperita L. (Peppermint) | Flavonoids, phenolics, terpenoids, essential oils | Usage in topical remedies, mouthwashes, toothpastes, bath products, and aromatherapy to reduce irritation and inflammation |

Herro and Jacob22 |

| 3 | Ocimum basilicum L. (Sweet basil) | Linalool, eugenol, methyl eugenol, estragole | Anti-inflammatory, analgesic, antipyretic, and antioxidant effects. It has been traditionally used for managing respiratory issues, wound healing, and stress relief |

Aminian et al.23 |

| 4 | Rosmarinus officinalis L. (Rosemary) | Rosmarinic acid, caffeic acid, camphor, ursolic acid, carnosic acid betulinic acid, and carnosol |

Antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and antimicrobial effects. It's also known to improve memory, relieve headaches, and manage stress and depression |

Andrade et al.24 |

| 5 | Thymus vulgaris L. (Thyme) | Thymol, eugenol, carvacrol, rosmarinic acid, linalool, apigenin, and p cymene |

Antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, and antiviral effects. It has been used traditionally for centuries for its potential therapeutic benefits, particularly in addressing respiratory ailments, digestive issues, and skin problems |

Dauqan and Abdullah25 |

| 6 | Mentha spicata L. (Spearmint) | Flavonoids, phenols, terpenoids, alkaloids, glycosides, carvone, limonene, and rosmarinic acid |

Carminative, antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, and antioxidant effects. It’s commonly used in traditional medicine for treating gastrointestinal issues, respiratory problems. |

Ojewumi et al.26 |

| 7 | Ocimum canum Sims (Sweet basil/African basil) |

Tannins, phenolic acids, saponins, tannins, limonene, terpenes, anthocyanins, phytosterols, and policosanols |

Used to treat conditions related to the kidneys, urinary bladder, Urethra, respiratory problems, digestive issues anxiety |

Kuralarasi and Revathilakshmi27 |

| 8 | Satureja sohendica L. (Summer savory) |

Polyphenols, flavonoids, thymol, naringenin, carvacrol, caffeic acid, luteolin, glycosides, chlorogenic acid, kaempferol, and rutin |

It has been traditionally used to relieve muscle pain, stomach and intestinal issues, and infectious diseases. Studies have also shown it to have antispasmodic, anti-diabetic, antimicrobial, anti-hyperlipidemic, antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and sedative properties |

Fierascu et al.28 |

| 9 | Stachys byzantine K. Koch (Lamb’s Ear) |

Terpenes, steroids, phenols, flavonoids, and α-tocopherol. Its essential oil is rich in compounds like 1,8-cineole, linalool, cubenol, germacrene-D, α-terpineol, menthone, and (Z)-lanceol acetate |

Anti-inflammatory, antibacterial, anxiolytic, antinephritic, vulnerary (for wound healing), antiseptic, anti-inflammatory, and astringent properties |

Bahadori et al.29 |

| 10 | Melissa officinalis L. (Lemon balm) | Flavonoids, terpenoids, phenolic acids, tannins, and essential oils |

Anxiolytic, antidepressant, and anti-inflammatory effects | Petrisor et al.30 |

| 11 | Marrubium vulgare L. (Horehound) | Polyphenols, flavonoids, phenylpropanoids, tannins, marrubiin, volatile oils, apigenin, luteolin, quercetin, glycosides |

Expectorant, antispasmodic, and antioxidant effects. It’s traditionally used for respiratory ailments like coughs, bronchitis, and whooping cough, and may also offer benefits in managing high blood pressure and reducing inflammation |

Aćimović et al.31 |

| 12 | Origanum syriacum L. (Syrian oregano) |

Terpenoids, phenols, carotenoids, flavonoids, thymol, carvacrol, and thymoquinone |

Antioxidant, antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, and anticancer activities. O. syriacum has been used in traditional medicine for respiratory issues, relieving stomach pain, and treating colds and toothache |

Mesmar et al.32 |

| 13 | Nepeta cataria L. (Catnip) | Essential oils, flavonoids, phenolic acids, and terpenoids | Antispasmodic, antiseptic, antitussive, antiasthmatic, anti-inflammatory, diuretic, and expectorant effects |

Nadeem et al.33 |

| 14 | Molucella laevis L. (Bells of Ireland) |

α-thujene, β-pinene, β-caryophyllene, monoterpenes, esters, fatty acids, and sterols |

Additionally, it's believed to have anti-inflammatory, diaphoretic, antispasmodic, carminative, antiemetic, and emmenagogue properties. It is able to manage mental disorders, high blood sugar, and lung diseases. Additionally, seeds and leaf sap are used to avoid dystocia and protracted infant birth, as well as to counteract the effects of bee stings and snake venom |

Hamed et al.34 |

| 15 | Ballota nigra L. (black horehound) | Diterpenoids like furanolabdane diterpenoids (ballonigrin, dehydrohispanolone, and hispanolone), flavonoids, and essential oils |

Treating upset stomach, nausea, and mild sleep disorders | Przerwa et al.35 |

| Ranunculaceae | ||||

| 16 | Ranunculus sceleratus L. (Kandira) | Flavonoids, steroids (like β-sitosterol), and glycosides of γ-lactones |

Used in treating infected wounds, scabies, leucoderma | Cao et al.36 |

| 17 | Aconitum anthora (Monkshood) | Diterpenoid alkaloids (aconitine, masaconitine), and flavonoid |

Used externally for pain relief, particularly for rheumatism and sciatica, and internally for fever, colds, and heart conditions |

Mariani et al.37 |

| 18 | Anemone coronaria L. (Poppy anemone) |

Triterpenoids, steroids, lactones, saponins, fats,saccharides, oils, and alkaloids | Help in relieving from eye and skin inflammation, emotional distress, menstrual pain, and respiratory problems |

Hao et al.38 |

| 19 | Clematis addisonii Britt. (Addison’s Leatherflower) |

Triterpenoid saponins, alkaloids, flavonoids, and volatile oils |

Treat urinary, rheumatic, and transmitted diseases, fever, eye infections, and dermatological problems |

Chen et al.39 |

| 20 | Delphinium dendunatum Wall. Ex Hook.f. and Thomson (Jadwar or Nirvisha) |

Alkaloids, flavonoids, and other compounds. Diterpenoid alkaloids, such as condelphine and denudatine, are particularly notable. Additionally, sterols, fatty acids, sugars, proteins, starch, and phenols |

Sedative, analgesic, and neuroprotective effects, and is used to treat a range of conditions including nerve disorders, seizures, and even poisoning. It’s also recognized for its digestive, diuretic, and wound healing properties |

Jain et al.40 |

| 21 | Nigella damascene L. (Love-in-a-Mist) |

Alkaloids, flavonoids, diterpenes, and triterpenes | Regulating menstruation, treating catarrhal affections, and acting as a diuretic and vermifuge agent |

Badalamenti et al.41 |

| 22 | Caltha palustris (Marsh marigold) | Tannins, glycosides (γ-lactones of protoanemonin and anemonin), berberine, saponins, flavonoids, vitamin C, bitterness, carotene, choline, and alkaloids |

It has been used to treat ailments like colds, sores, fits, and anemia, and its root has been used as an antirheumatic, diaphoretic, emetic, and expectorant |

Liakh et al.42 |

| 23 | Acatea racemosa L. (Black cohosh) | Triterpenoid glycosides like actein, cimicifugoside M, and 27-deoxyactein, as well as phenolic acids, alkaloids, and resin |

Potential benefits for menopause, menstrual irregularities, and certain gynecological conditions |

Salari et al.43 |

| 24 | Naravelia zeylanica (L.) DC (Cimbing vine) |

Alkaloids, flavonoids, tannins, terpenoids, carbohydrates, and phytosterols |

Used in the treatment of helminthiasis, leprosy, odontalgia, dermatopathy, rheumatalgia, wounds, colic inflammation, and ulcers |

Varghese et al.44 |

| 25 | Adonis annua L. (Pheasant's eye) | Cardiac glycosides, flavones, carotenoids, and coumarins |

Antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, antibacterial, and anticancer properties |

Ouasti et al.45 |

| 26 | Pulsatilla vulgaris Mill. (Mugwort) | Triterpenoid saponins, flavonoids, alkaloids, carboxylic acids, phenolic acids |

Pulsatilla is used for painful conditions of the male reproductive system, like orchitis and epididymitis, as well as female reproductive issues such as dysmenorrhea and ovaralgia. It's also effective for tension headaches, hyperactivity, insomnia, gastrointestinal disorders, and urinary tract issues |

Laska et al.46 |

| 27 | Helleborus foetidus L. (Stinkinf hellebore) |

Steroidal glycosides, bufadienolides, saponins, anemonin, quercetin glycosides, and phenolic glucosides |

Anti-cancer, antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, analgesic, anti-hyperglycaemic, immunomodulatory, and antibacterial properties |

Iguchi et al.47 |

| 28 | Aquilegia vulgaris L. (Columbine) | Flavonoids, cyanogenic glycosides, alkaloids, tannins, isocytisoside, and cyanogenic glycosides like dhurrin and triglochinin, caffeic, chlorogenic, p-coumaric, ferulic, protocatechuic, sinapic, vanillic, and p-hydroxybenzoic acids |

Astringent, depurative, diaphoretic, diuretic, and parasiticide effects. Treats measles, smallpox, kidney stones, uterine bleeding, and head lice |

Nomin et al.48 |

| 29 | Myosurus apetalus C.Gay (Bristly mousetail) |

Flavonoids, alkaloids, and phenols | It has been used medicinally by some Native American tribes, including the Navaho-Ramah, as a life medicine and to protect against witches. It is also sometimes used as a fertility booster, anti-venom, anti-fungal, and anti-bacterial agent, and for its antioxidant properties |

Munyali et al.49 |

| 30 | Thalictrum alpinum L. (Alpine meadow-rue) |

Alkaloids, essential oils, glycosides, phenols, and terpenoids |

Antitumor, antiamebic, antimicrobial, hypotensive, antitussive, and HIV antiviral properties. It helps in relieving jaundice, snake bite, rheumatism, stomachache, wounds, ophthalmic, swellings, uterine tumors, paralysis, fever, joint pain, headache, nervous disorders, toothache, diarrhoea, diuretic, piles, peptic ulcer, dyspepsia, and convalescence |

Singh et al.50 |

| Zingiberaceae | ||||

| 31 | Globba pendula Roxb. (Dancing Ladies or Dancing Girls Ginger) |

Indirubin, vanillic acid, labdane diterpene, 2 (3H)- benzoxazolone, vanillin, beta-sitosteryl-D- glucopyranoside, 7-alpha-hydroxysitosterol, beta-sitosterol, and isoandrographolide |

Treating rheumatism, osteoarthritis, and postpartum issues | Ha et al.51 |

| 32 | Zingiber officinale (Ginger) | Essential oils, flavonoids, phenolic compounds, saponins, alkaloids, glycosides, terpenoids, and steroids |

Used in treating nausea, vomiting, digestion, inflammation, and pain |

Abdullahi et al.52 |

| 33 | Curcuma longa L. (Turmeric) | Demethoxycurcumin, bisdemethoxycurcumin, and essential oils like turmerone, ar-turmerone, and zingiberene |

It has anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and anticancer effects Curcumin, its major ingredient, has been connected to a numberof health advantages, including better digestion, less inflammation, and possible disease prevention |

Iweala et al.53 |

| 34 | Elettaria cardamomum (L.) Maton (Cardamom) |

1,8-cineole, α-terpinyl acetate, linalool, and limonene | Aiding digestion, reducing inflammation, and potentially combatin infections. It's used in traditional medicine for conditions like asthma, nausea, and diarrhoea, antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties |

Jena et al.54 |

| 35 | Boesenbergia rotunda (L.) Mansf. (Fingerroot or Krachai) |

Alpinetin, Cardamonin, Pinostrobin, Pinocembrin, Geraniol, Panduratin, Boesenbergin, Krachizin, Rotundaflavone, Silybin |

Anti-inflammatory, anti-oxidant, anticancer, antidiabetic, anti-allergic, anti-obesity, aphrodisiac, and antimicrobial activities |

Hop and Son55 |

| 36 | Roscoea capitata Sm. | Alkaloids, flavonoids, phenols, quinones, saponins, steroids, tannins, proteins, and terpenoids, essential oils (β-eudesmol, guaiac acetate, and γ-eudesmol) |

Anti-rheumatic, febrifuge, galactagogue, and tonic effects. It’s also believed to be beneficial for hematemesis, excessive thirst, and rheumatic pain |

Devkota and Timalsina56 |

| 37 | Haniffia albiflora K.Larsen and J.Mood |

Flavonoids, alkaloids, phenols, glycosides, and tannins | Malaria, wound healing, headache, anti-parasitic activity, scabies treatment, and also used to kill germs |

Saha et al.57 |

| 38 | Wurfbainia aromatica (Roxb.) Skornick. and A.D.Poulsen |

β-pinene and α-pinene | Anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties. Its essential oils are also used in perfumes and fragrances. Specifically, the fruits are used for their medicinal properties, including dampness elimination, diarrhea treatment, miscarriage prevention, spleen warming, and as appetite stimulants |

Sagayap et al.58 |

| 39 | Geocharis aurantiaca Ridl.-Johor |

Flavonoids and alkaloids | Extracts and compounds from Geocharis species have shown antimicrobial, antiviral, and anti-inflammatory activities, as well as cytotoxic effects on cancer cells |

Nurains et al.59 |

| 40 | Scaphochlamys atroviridis Holttum |

Flavonoids, alkaloids, phenols, p-cymene, pinene, α-terpineol |

Anti-inflammatory, analgesic, and wound healing effects. Treat skin conditions, pain, and fever |

Searle60 |

CONCLUSION

The exploration of medicinal plants from the Lamiaceae, Ranunculaceae, and Zingiberaceae families reveals a rich tapestry of bioactive compounds with significant therapeutic potential. Each family exhibits a distinct phytochemical profile, contributing to their unique medicinal properties and ecological roles. These plant families have significantly influenced traditional medicine across cultures, forming the basis for numerous remedies that continue to be used today. Ongoing research into these families continues to uncover new compounds and validate their historical medicinal uses, paving the way for innovative pharmaceutical and nutraceutical developments. The intersection of traditional knowledge and modern scientific exploration holds remarkable promise for enhancing human health and wellness. As our understanding of these biodiverse families deepens, it becomes increasingly clear that further investigation into the mechanisms of action of these phytochemicals and the development of safe, effective therapeutic applications is crucial. This continued research not only enriches our knowledge of herbal medicine but also opens new avenues for improving human health through nature-derived compounds.

SIGNIFICANCE STATEMENT

The growing prevalence of chronic diseases and antibiotic-resistant pathogens has spurred interest in natural remedies from medicinal plants, particularly those from the Lamiaceae, Ranunculaceae, and Zingiberaceae families. This review highlights key bioactive compounds-such as phenolics, terpenoids, and alkaloids-found in these plants, along with their pharmacological activities, including anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial, antioxidant, and anticancer properties. It identifies specific plant species with therapeutic potential and emphasizes the need for further research on these compounds and their synergistic effects. Overall, the review aims to advance the understanding of natural product chemistry and ethnopharmacology, encourage conservation of medicinal plants, promote collaboration across disciplines, and support the development of sustainable, plant-based medicines to improve global health.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to express their gratitude to Prof. Ina Aditya Shastri, Vice-Chancellor, Banasthali Vidyapith, Rajasthan, for her support and encouragement. We also thank DST for giving networking support through the FIST program at the Department of Bioscience and Biotechnology, Banasthali, along with the Bioinformatics Center, Banasthali Vidyapith, funded by DBT (Grant Number: BT/HRD/01/28/2020).

REFERENCES

- Sharma, S.K. and A. Alam, 2024. Ethnobotanical importance of families Apocynaceae, Asteraceae, and Fabaceae (Angiosperms) among Rajasthan tribes, India. Plant Sci. Today, 11: 57-76.

- Gibson, E.L., J. Wardle and C.J. Watts, 1998. Fruit and vegetable consumption, nutritional knowledge and beliefs in mothers and children. Appetite, 31: 205-228.

- Shreya, R., B. Sharma, A. Alam and S.K. Sharma, 2023. Ethnomedicinal importance of Fabaceae family (Angiosperms) among the tribes of Rajasthan, India. Nat. Res. Hum. Health, 3: 237-247.

- Priyadarshini, H.S.S., S.A. Kumar, G. Sakshi and N. Rahul, 2019. Phytochemical screening and antioxidant activity of methanolic extract of Ocimum sanctum Linn. leaves. GSC Biol. Pharm. Sci., 8: 22-33.

- Sharma, S.K., P. Baliyan and A. Alam, 2024. Momordica charantia L.: Unlocking its potential as a nutritional food through ethnomedicinal and pharmacological properties. Res. J. Bot., 19: 31-40.

- Hamburger, M. and K. Hostettmann, 1991. Bioactivity in plants: The link between phytochemistry and medicine. Phytochemistry, 30: 3864-3874.

- Oniyangi, O. and D.H. Cohall, 2020. Phytomedicines (medicines derived from plants) for sickle cell disease. Cochrane Database of Syst. Rev.

- Alam, A., P. Baliyan, V. Sharma and Mazhar-ul-Islam, 2021. Potential of bryophytes in nanotechnolohy: An overview. J. Phytonanotechnol. Pharm. Sci., 1: 1-3.

- Sah, S., S.K. Sharma, A. Alam and P. Baliyan, 2024. Therapeutic and nutritive uses of Macrotyloma uniflorum (Lam.) Verdc. (Horsegram), a somewhat neglected plant of the family Fabaceae. Nat. Resour. Hum. Health, 4: 34-50.

- Saxena, M., J. Saxena, R. Nema, D. Singh and A. Gupta, 2013. Phytochemistry of medicinal plants. J. Pharmacogn. Phytochem., 1: 168-182.

- Haas, R.A., I. Crișan, D. Vârban and R. Vârban, 2024. Aerobiology of the family Lamiaceae: Novel perspectives with special reference to volatiles emission. Plants, 13.

- Goo, Y.K., 2022. Therapeutic potential of Ranunculus species (Ranunculaceae): A literature review on traditional medicinal herbs. Plants, 11.

- Boonma, T., S. Saensouk and P. Saensouk, 2023. Diversity and traditional utilization of the zingiberaceae plants in Nakhon Nayok Province, Central Thailand. Diversity, 15.

- Rachkeeree, A., K. Kantadoung, R. Suksathan, R. Puangpradab, P.A. Page and S.R. Sommano, 2018. Nutritional compositions and phytochemical properties of the edible flowers from selected Zingiberaceae found in Thailand. Front. Nutr., 5.

- Cocan, I., E. Alexa, C. Danciu, I. Radulov and A. Galuscan et al., 2018. Phytochemical screening and biological activity of Lamiaceae family plant extracts. Exp. Ther. Med., 15: 1863-1870.

- Moshari-Nasirkandi, A., A. Alirezalu, H. Alipour and J. Amato, 2023. Screening of 20 species from Lamiaceae family based on phytochemical analysis, antioxidant activity and HPLC profiling. Sci. Rep., 13.

- Deng, K.Z., Y. Xiong, B. Zhou, Y.M. Guan and Y.M. Luo, 2013. Chemical constituents from the roots of Ranunculus ternatus and their inhibitory effects on Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Molecules, 18: 11859-11865.

- Bhargava, S., K. Dhabhai, A. Batra, A. Sharma and B. Malhotra, 2012. Zingiber officinale: Chemical and phytochemical screening and evaluation of its antimicrobial activities. J. Chem. Pharm. Res., 4: 360-364.

- Ajagun, E.J., J.A. Angalapele, P.N. Nwaiwu, M.A. Alabi, J.A. Oladimeji-Salami and U. Amba, 2017. Phytochemical screening and effect of temperature on proximate analysis and mineral composition of Zingiber officinale Rosc. Biotechnol. J. Int., 18.

- Ramadanil, Damry, Rusdi, B. Hamzah and M.S. Zubair, 2019. Traditional usages and phytochemical screenings of selected Zingiberaceae from Central Sulawesi, Indonesia. Pharmacogn. J., 11: 505-510.

- Ghorbani, A. and M. Esmaeilizadeh, 2017. Pharmacological properties of Salvia officinalis and its components. J. Tradit. Complementary Med., 7: 433-440.

- Herro, E. and S.E. Jacob, 2010. Mentha piperita (peppermint). Dermatitis, 21: 327-329.

- Aminian, A.R., R. Mohebbati and M.H. Boskabady, 2022. The effect of Ocimum basilicum L. and its main ingredients on respiratory disorders: An experimental, preclinical, and clinical review. Front. Pharmacol., 12.

- Andrade, J.M., C. Faustino, C. Garcia, D. Ladeiras, C.P. Reis and P. Rijo, 2018. Rosmarinus officinalis L.: An update review of its phytochemistry and biological activity. Future Sci. OA, 4.

- Dauqan E.M.A., and A. Abdullah, 2017. Medicinal and functional values of thyme (Thymus vulgaris L.) herb. J. Appl. Biol. Biotech., 5: 17-22.

- Ojewumi, M.E., S.O. Adedokun, O.J. Omodara, E.A. Oyeniyi, O.S. Taiwo and E.O. Ojewumi, 2017. Phytochemical and antimicrobial activities of the leaf oil extract of Mentha spicata and its efficacy in repelling mosquito. Int. J. Pharm. Res. Allied Sci., 6: 17-27.

- Kuralarasi, R. and S. Revathilakshmi, 2019. Phytochemical characterization and antioxidative property of Ocimum canum Sims. Global J. Pharm. Pharm. Sci., 7.

- Fierascu, I., C.E. Dinu-Pirvu, R.C. Fierascu, B.S. Velescu, V. Anuta, A. Ortan and V. Jinga, 2018. Phytochemical profile and biological activities of Satureja hortensis L.: A review of the last decade. Molecules, 23.

- Bahadori, M.B., G. Zengin, L. Dinparast and M. Eskandani, 2020. The health benefits of three Hedgenettle herbal teas (Stachys byzantine, Stachys inflata, and Stachys lavandulifolia)-profiling phenolic and antioxidant activities. Eur. J. Integr. Med., 36.

- Petrisor, G., L. Motelica, L.N. Craciun, O.C. Oprea, D. Ficai and A. Ficai, 2022. Melissa officinalis: Composition, pharmacological effects and derived release systems-A review. Int. J. Mol. Sci., 23.

- Aćimović, M., K. Jeremić, N. Salaj, N. Gavarić, B. Kiprovski, V. Sikora and T. Zeremski, 2020. Marrubium vulgare L.: A phytochemical and pharmacological overview. Molecules, 25.

- Mesmar, J., R. Abdallah, A. Badran, M. Maresca and E. Baydoun, 2022. Origanum syriacum phytochemistry and pharmacological properties: A comprehensive review. Molecules, 27.

- Nadeem, A., H. Shahzad, B. Ahmed, T. Muntean, M. Waseem and A. Tabassum, 2022. Phytochemical profiling of antimicrobial and potential antioxidant plant: Nepeta cataria. Front. Plant Sci., 13.

- Hamed, A., N.A. Abdelaty, E.Z. Attia and S.Y. Desoukey, 2020. Phytochemical investigation of saponifiable matter & volatile oils and antibacterial activity of Moluccella laevis L., family Lamiaceae (Labiatae). J. Adv. Biomed. Pharm. Sci., 3: 213-220.

- Przerwa, F., A. Kukowka and I. Uzar, 2020. Ballota nigra L.-An overview of pharmacological effects and traditional uses. Herba Pol., 66: 56-65.

- Cao, S., M. Hu, L. Yang, M. Li and Z. Shi et al., 2022. Chemical constituent analysis of Ranunculus sceleratus L. using ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography coupled with quadrupole-orbitrap high-resolution mass spectrometry. Molecules, 27.

- Mariani, C., A. Braca, S. Vitalini, N. de Tommasi, F. Visioli and G. Fico, 2008. Flavonoid characterization and in vitro antioxidant activity of Aconitum anthora L. (Ranunculaceae). Phytochemistry, 69: 1220-1226.

- Hao, D.C., X. Gu and P. Xiao, 2017. Anemone medicinal plants: Ethnopharmacology, phytochemistry and biology. Acta Pharm. Sin. B, 7: 146-158.

- Chen, K.C., M.F. Sun, S.C. Yang, S.S. Chang, H.Y. Chen, F.J. Tsai and C.Y.C. Chen, 2011. Investigation into potent inflammation inhibitors from traditional Chinese medicine. Chem. Biol. Drug Des., 78: 679-688.

- Jain, R., M.Z. Siddiqui, M. Waseem, R. Raghav, A. Jabin and S. Jhanjee, 2021. Therapeutic usefulness of Delphinium denudatum (Jadwar): An update. Int. J. Herb. Med., 9: 97-100.

- Badalamenti, N., A. Modica, G. Bazan, P. Marino and M. Bruno, 2022. The ethnobotany, phytochemistry, and biological properties of Nigella damascena-A review. Phytochemistry, 198.

- Liakh, V., R. Konechna, A. Mylyanych, L. Zhurakhivska, I. Hubytska and V. Novikov, 2020. Caltha palustris. Analytical overview. ScienceRise: Pharm. Sci., 2: 51-56.

- Salari, S., M.S. Amiri, M. Ramezani, A.T. Moghadam, S. Elyasi, A. Sahebkar and S.A. Emami, 2021. Ethnobotany, Phytochemistry, Traditional and Modern Uses of Actaea racemosa L. (Black Cohosh): A Review. In: Pharmacological Properties of Plant-Derived Natural Products and Implications for Human Health, Barreto, G.E. and A. Sahebkar, Springer, Cham, Switzerland, ISBN: 978-3-030-64872-5, pp: 403-449.

- Varghese, N.P., T. Shekshavali, B. Prathib and I.J. Kuppast, 2017. A review on pharmacological activities of Naravelia zeylanica. Res. J. Pharmacol. Pharmacodyn., 9: 35-38.

- Ouasti, M., P. Subhasis, D.S. Mahanty, R.W. Bussmann and M. Elachouri, 2024. Adonis aestivalis L. Adonis annua L. Adonis dentata Delile Ranunculaceae. In: Ethnobotany of Northern Africa and Levant, Bussmann, R.W., M. Elachouri and Z. Kikvidze (Eds.), Springer International Publishing, New York, ISBN: 978-3-031-13933-8, pp: 1-6.

- Łaska, G., A. Sienkiewicz, M. Stocki, J.K. Zjawiony and V. Sharma et al., 2019. Phytochemical screening of Pulsatilla species and investigation of their biological activities. Acta Societatis Botanicorum Poloniae, 88.

- Iguchi, T., A. Yokosuka, R. Kawahata, M. Andou and Y. Mimaki, 2020. Bufadienolides from the whole plants of Helleborus foetidus and their cytotoxicity. Phytochemistry, 172.

- Nomin, M., G. Odontuya and B. Mungunshagai, 2018. Review analysis on phytochemical and biological activity studies on plants of Aquilegia L. Bull. Inst. Chem. Chem. Technol., 6: 64-71.

- Munyali, D.A., A.C.T. Momo, G.R.B. Fozin, P.B.D. Defo, Y.P. Tchatat, B. Lieunang and P. Watcho, 2020. Rubus apetalus (Rosaceae) improves spermatozoa characteristics, antioxidant enzymes and fertility potential in unilateral cryptorchid rats. Basic Clin. Andrology., 30.

- Singh, H., D. Singh and M.M. Lekhak, 2023. Ethnobotany, botany, phytochemistry and ethnopharmacology of the genus Thalictrum L. (Ranunculaceae): A review. J. Ethnopharmacol., 305.

- Ha, L.M., N.T. Phuong, N.T.T. Hien, P.T. Tam, D.T. Thao and D.T.T. Huyen, 2021. In vitro and in vivo anti-inflammatory activity of the rhizomes of Globba pendula Roxb. Nat. Prod. Commun., 16.

- Abdullahi, A., A. Khairulmazmi, S. Yasmeen, I.S. Ismail and A. Norhayu et al., 2020. Phytochemical profiling and antimicrobial activity of ginger (Zingiber officinale) essential oils against important phytopathogens. Arabian J. Chem., 13: 8012-8025.

- Iweala, E.J., M.E. Uche, E.D. Dike, L.R. Etumnu and T.M. Dokunmu et al., 2023. Curcuma longa (Turmeric): Ethnomedicinal uses, phytochemistry, pharmacological activities and toxicity profiles-A review. Pharmacol. Res. Mod. Chin. Med., 6.

- Jena, S., A. Ray, A. Sahoo, B.B. Champati and B.M. Padhiari et al., 2021. Chemical composition and antioxidant activities of essential oil from leaf and stem of Elettaria cardamomum from Eastern India. J. Essent. Oil Bear. Plants, 24: 538-546.

- Hop, N.Q. and N.T. Son, 2023. Boesenbergia rotunda (L.) Mansf.: A review of phytochemistry, pharmacology, and pharmacokinetics. Curr. Org. Chem., 27: 1842-1856.

- Devkota, H.P. and D. Timliasina, 2021. Traditional uses, phytochemistry and biological activities of Roscoea purpurea Sm. Ethnobotany Res. Appl., 22.

- Saha, K., R.K. Sinha and S. Sinha, 2020. Distribution, cytology, genetic diversity and molecular phylogeny of selected species of Zingiberaceae-A review. Feddes Repertorium, 131: 58-68.

- Sagayap, C., P. Chuysinuan, N. Chutiwitoonchai, P. Pripdeevech and W. Kaewsri et al., 2025. An anisole derivative in the essential oil of Wurfbainia schmidtii with virucidal activity against SARS-CoV-2 and anti-inflammatory properties. Nat. Prod. Commun., 20.

- Nurainas, N., W. Zulaspita, T.A. Febriamansyah, S. Syamsuardi and A.D. Poulsen, 2024. A recircumscription of Geocharis (Zingiberaceae) as a result of the discovery of a new species in Sumatra, Indonesia. Phytokeys, 244: 15-22.

- Searle, R.J., 2010. The genus Scaphochlamys (Zingiberaceae-Zingibereae): A compendium for the field worker. Edinburgh J. Bot., 67: 75-121.

How to Cite this paper?

APA-7 Style

Sharma,

S.K., Baliyan,

P., Alam,

A. (2025). Bioactive Compounds in Lamiaceae, Ranunculaceae, and Zingiberaceae: A Review of Healing Potential. Trends in Biological Sciences, 1(1), 12-25. https://doi.org/10.21124/tbs.2025.12.25

ACS Style

Sharma,

S.K.; Baliyan,

P.; Alam,

A. Bioactive Compounds in Lamiaceae, Ranunculaceae, and Zingiberaceae: A Review of Healing Potential. Trends Biol. Sci 2025, 1, 12-25. https://doi.org/10.21124/tbs.2025.12.25

AMA Style

Sharma

SK, Baliyan

P, Alam

A. Bioactive Compounds in Lamiaceae, Ranunculaceae, and Zingiberaceae: A Review of Healing Potential. Trends in Biological Sciences. 2025; 1(1): 12-25. https://doi.org/10.21124/tbs.2025.12.25

Chicago/Turabian Style

Sharma, Supriya, Kumari, Prachi Baliyan, and Afroz Alam.

2025. "Bioactive Compounds in Lamiaceae, Ranunculaceae, and Zingiberaceae: A Review of Healing Potential" Trends in Biological Sciences 1, no. 1: 12-25. https://doi.org/10.21124/tbs.2025.12.25

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.