Comparative Analysis of Physico-Chemical Properties, Morphological Traits, and Sensory Quality of Jelly from Three Guava Varieties in the Hilly Region of Chattogram, Bangladesh

| Received 24 Apr, 2025 |

Accepted 29 Jun, 2025 |

Published 30 Jun, 2025 |

Background and Objective: Guava (Psidium guajava), often referred to as the "poor man’s fruit", is a nutrient-rich tropical crop valued for its health benefits. Despite its potential, limited comparative studies exist on the varietal differences in morphological, nutritional, and processing qualities of guava in Bangladesh’s hilly Chattogram Region. This study aimed to evaluate and compare the physico-chemical, morphological, and nutritional attributes of three guava varieties (PG1, PG2, and PG3-a hybrid) and assess the sensory properties of jelly made from them versus commercially available jelly. Materials and Methods: Three guava varieties were examined for their morphological traits (e.g., fruit shape, weight, pulp and seed weight), and physico-chemical parameters such as pH, TSS, titratable acidity, moisture, dry matter, protein, fat, sugar, and vitamin C content. Homemade jelly was prepared from each variety and compared with market jelly through sensory evaluation based on color, flavor, taste, and smell. Statistical analyses, including ANOVA and descriptive statistics, were performed, and a p<0.05 was considered statistically significant were employed to assess significant differences among variables. Results: Significant varietal differences were observed across morphological and nutritional traits. For instance, pH ranged from 4.02 to 5.03, TSS from 9.24 to 12.16°Brix, and vitamin C content from 28.37 to 40.20 mg/100 g. Homemade and market jellies had comparable carbohydrate (65-71%) and moisture content (17-23%), with homemade jelly showing superior flavor and acceptability. Among the varieties, jelly from PG1 and PG3 scored highest in sensory evaluations, while market jelly was rated highest for its appealing pinkish color. Homemade jelly showed stable storage properties for up to 6 months, with only slight acidity changes after 90 days. Conclusion: The three guava varieties demonstrated notable differences in morphological and nutritional traits, with PG1 emerging as the most promising based on sensory appeal and nutrient content. These findings support the commercial potential of selected guava cultivars for value-added product development in the Chattogram Region. Future research may explore larger-scale trials and consumer preferences across broader demographics.

| Copyright © 2025 Hojaifa et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. |

NTRODUCTION

A tropical fruit, powerful in well-known nutrients, is guava. The fruit easily fits into the category of new functional foods, sometimes known as “super-fruits”, because of its distinct flavor and taste as well as its health-promoting attributes.

Fruits are nature’s gift to mankind. Guava is known as “peyara/pearah or goyam” locally, which is one of the most vital and widely cultivated fruits in Bangladesh. The scientific name of the guava is Psidium guajava, but in English, it is called apple guava, which belongs to the Myrtaceae family and genus Psidium. It is very popular as a commercial crop in the Indian Subcontinent due to its higher nutritive values, growing in diverse agroclimatic conditions, fruit harvest quickly, and high profitability1. Unripe fruits are usually hard in texture and starchy, and important commercial fruits in tropical and subtropical areas are acidic in taste and sometimes astringent after ripening. This superfruit contains numerous health-promoting qualities and is rich in dietary fiber, antioxidants, vitamins A, B, and C, as well as minerals such as calcium, phosphorus, potassium, copper, and manganese2. Vitamin C content is four times higher in a single apple guava than in a single orange. The “Strawberry Guava” notably contains only 30-40 mg of vitamin C per 100 g and the content is still a high percentage (62%)3. Many favorite and tasty items are made from guava, like jellies, syrup, jam, paste, baby foods, cheese, puree, beverages, wine, dairy items, bakery, and other processed products, and these products are imported by many countries also4. Misty- and Kazi-Guava are normally planted domestically in Bangladesh, but nowadays these are also cultivated commercially, while the Hybrid VNR-Bihi guava is also popular in the supermarket and has high commercial value.

Due to their unique flavor and nutritional composition, guavas are becoming a highly desired item in the international fruit trade. It has been a popular selection for farmers due to its excellent flavor and several health advantages. As observed in Table 1, Bangladesh’s guava fruit production rate has been growing steadily over the past ten years (from 2013-14 to 2022-23), rising by more than 26%5.

As shown in Table 2, in consideration of the Total World Guava Production, Bangladesh was placed in the 8th rank and the percentages are as follows: India: 42.1%, Indonesia: 9.9%, Pakistan: 6.7%, Bangladesh: 5.6%, Egypt: 1.8% etc., in the Year 2023-2024 (*Total amount of Guava production in the World, 2023-24)6. When determining the nutritional relevance of edible fruits and vegetables, proximate and nutrient analysis is essential7. So, the present study aimed to investigate the morphology and nutrient analyses as well as their processed food products.

| Table 1: | Total production of guava in Bangladesh for 10 years | |||

| Year | Total production (metric tons) | Year | Total production (metric tons) |

| 2013-14 | 202,504 | 2018-19 | 236,881 |

| 2014-15 | 206,425 | 2019-20 | 226,028 |

| 2015-16 | 214,308 | 2020-21 | 243,957 |

| 2016-17 | 229,376 | 2021-22 | 254,857 |

| 2017-18 | 241,504 | 2022-23 | 256,106 |

| Source: Yearbook of Agricultural Statistics-2015, published in July 2016 to 2021, Series 27 to 33. Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics (BBS), Statistics and Informatics Division (SID), Ministry of Planning, Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh, www.bbs.gov.bd | |||

| Table 2: | Top 10-guava production by country, 2024 | |||

| Rank | Country | Production in MT, 2011 | Percentage | Country | Production in MT, 2023 | Percentage | Overall (%) |

| 1 | India | 17,650,000 | 53.244 | India | 24,968,000 | 54.6 | 42.1 |

| 2 | China | 4,366,300 | 13.17 | China | 3,790,000 | 8.28 | - |

| 3 | Thailand | 2,550,600 | 7.69 | Indonesia | 3,561,867 | 7.79 | 9.9 |

| 4 | Pakistan | 1,784,300 | 5.38 | Pakistan | 2,677,017 | 5.89 | 6.7 |

| 5 | Mexico | 1,632,650 | 4.93 | Mexico | 2,441,496 | 5.34 | - |

| 6 | Indonesia | 1,313,540 | 3.96 | Brazil | 2,057,765 | 4.5 | - |

| 7 | Brazil | 1,188,910 | 3.59 | Malawi | 1,696,121 | 3.71 | - |

| 8 | Bangladesh | 1,047,850 | 3.16 | Thailand | 1,635,233 | 3.58 | 5.6 |

| 9 | Philippines | 825,676 | 2.49 | Bangladesh | 1,458,554 | 3.19 | - |

| 10 | Nigeria | 790,200 | 2.38 | Vietnam | 1,439,273 | 3.15 | - |

| Source: World Atlas, Top Guava Producing Countries in the World, 2011, www.worldatlas.com/articles/top-guava-producing-countries-in-the-world.html | |||||||

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study area: The study was conducted as part of a thesis project from 2017 to 2018. The samples were collected in September and October of 2017, and all the biochemical tests were carried out in the University of Science and Technology Chittagong (USTC) Laboratory.

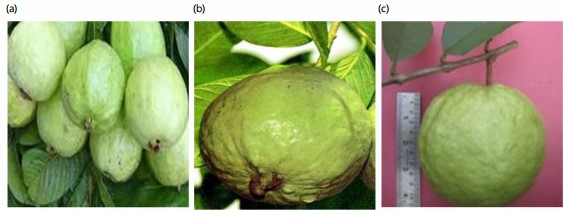

Collection of the sample: The three varieties of Guava, namely “Misty guava” denoted as “PG1" or local name “chini peyara”, “Kazi Guava” denoted as “PG2", and “VNR-Bihi Guava” denoted as “PG3", which is a hybrid variety, were selected in the present study. Figure 1 illustrates the three types of guavas used in the present study.

Collection of PG1 (Misty Guava): The yellow-green PG1 were harvested from the mountainous soil area of Bandarban, Chattogram. They have a diameter of 5.3/4.45/5.6 cm, a glossy and smooth surface, bright yellow skin when ripe, white and red flesh that is very appealing, soft flesh texture, delicious taste, and very soft seeds. The fruit was collected in September and October of 2017. Usually, these guava bushes flower twice a year in March or April and October or November, and are collected from the Bangabandhu Department of Crop Botany (2006). Digital Herbarium of Crop Plants: Rahman, Sheikh Mujibur. Developed May 5, 2017, by Bangladesh Agricultural University (BAU-1), Mymensingh, Bangladesh. Md. Abdul Baset Mia (Ed.). Origin: Regional.

Collection of PG2 (Kazi Guava): The PG2 was also collected from the Bandarban hill district, which is green when raw and yellowish when ripe, and the shape is oblong. Fruits are fleshy and crispy, a little sour and tasty. Seeds are hard and profuse. The average fruit weight is 60 g. The PG2 plants are quickly growing and about 5-7 m in height. The first ripen in July-August and the second fruit ripen in February in the same year. High fruit-yielding variety, produces fruits twice in a year, plant medium, 340-360 seeds/fruit, seed hard, 1000-seed weight 3.5-4.0 g, fruit initiation within one year after plantation.

Source: Digital Herbarium of Crop Plants, Department of Crop Botany, Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman Agricultural University, May 5, 2017, Md. Abdul Baset Mia, Developed by Bangladesh Agriculture Research Institute (BARI), Gazipur, Bangladesh, Year of Release: 1985, Origin: Thailand.

Collection of PG3 (VNR-Bihi hybrid variety of Guava): This variety of guava was collected from Super shops and local fruit shops (Origin: India, Native: Central America) because it is available all the time in the market. Some characteristics are as follows: Average fruit size -300-1000 g per fruit, Uniform and appealing fruit color, suitable for all types of soil, Good balance of acid and sugar, etc. This guava has fewer seeds and thick pulp, suitable for long-distance transport and a longer shelf life of 15 days-VNR Nursery, India8.

Sample preparation: The mature, fresh green guavas were spread out on various trays after being cleaned under running tap water. After that, the guavas were sliced into little pieces and left to dry in the sun for 6 or 7 days. Once more, they were dried in an incubator for 24 hrs at 37°C. Next, dry chopped guavas were ground into fine powders by repeatedly processing them in a high-speed blender until powder was formed. Powders were kept in an airtight container. Fresh or powdered guava was utilized as a sample in the experiment.

All the biochemical tests were performed 3 times for all three samples.

Determination of pH: At first, 2 g of dried guava powder was thoroughly blended using 30 mL of distilled water. Whatman No. 1 filter paper was then used to filter this mixture. A pH meter was used to determine the pH of the clear supernatant after the filtrate had been centrifuged for 10 min at 5000 rpm.

Determination of total soluble solids (TSS): The TSS was determined by the Refractometer as degree Brix (°B). At first, 2 g of fresh Guava was taken into a mortar and smashed well. Then, a drop of juice was squeezed on the prism of the Abbe Refractometer, and the percent of TSS was obtained from the direct reading of the instrument as recorded.

Determination of titratable acidity (TA): The TA is the total amount of acid present in the juice and is determined by titration using a standard solution of sodium hydroxide, which can be expressed as an equivalence of any organic acid, such as citric acid, malic acid, etc.9.

Determination of moisture content: Moisture content was determined by the conventional method. At first, 2 g of Guava was weighed in a porcelain crucible and heated in an electrical oven for about 6 hrs at 100°C. It was then cooled in desiccators and weighed again. For a constant weight, the crucible with the sample was heated repeatedly and weighed after cooling9.

Determination of dry matter content: The percent dry matter content of the dry guava powder was calculated from the data obtained during moisture estimation using the following formula9:

Determination of total sugar content: The total sugar content of the pineapple’s edible section was calculated using Anthrone’s method10.

Determination of reducing sugar content: Reducing sugar content of guava juice was determined by the Dinitro-salicylic acid method10,11.

Determination of non-reducing sugar: Sucrose content was calculated from the following formula11:

Determination of water-soluble protein content: Using the Folin-Lowry method12, the water-soluble protein content of guava juice was ascertained, using bovine serum albumin (BSA) as a reference.

Determination of lipid content: Lipid contents of the dried powder of Guava were determined by the method of Bligh and Dyer13.

Detection of phenolic compound presence: After a slight modification, the Folin-Ciocalteu methods14 were used to determine the presence of phenolic content: 0.2 mL of the diluted sample extract was placed in a test tube with 1.0 mL of a 1/10 dilution of Folin-Ciocalteu reagent in water; the tubes were then left to stand at room temperature for 30 min with intermittent shaking for color development; the color change indicates the presence of phenols in guava juice.

Detection of flavonoid presence: The presence of total flavonoid content of guava extract was determined by the aluminum chloride colorimetric method15. About 1 mL of sample was mixed with 1 mL of methanolic AlCl3. The 6H2O solution in a 1:1 ratio. A blank solution was also prepared by distilling water with a methanolic solution in a 1:1 ratio. Both the mixtures were incubated for 20 min at room temperature in a dark place. The color change showed the presence of flavonoid compounds.

|

Determination of vitamin C: The vitamin C content of guava was determined by the dichlorophenol indophenol (DCPIP) method16. First, 10 mL of 4% oxalic acid was added to 5 mL of guava fruit solution in a 100 mL conical flask. The DCPIP solution (5×10–4 mol/L) was then added to the mixture until a pink tint developed, which lasted for 30 sec.

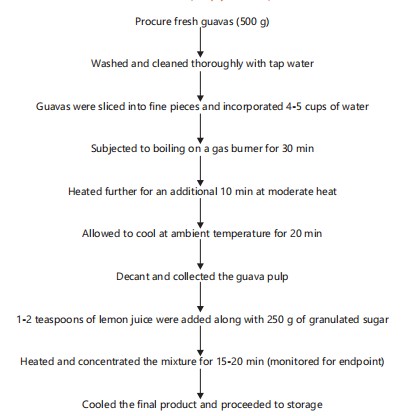

Guava jelly preparation and sensory evolution: Two guava types, PG1 and PG3, were utilized to make the jelly. The steps used to prepare the jelly are depicted in the flow chart.

Brief details of jelly preparation: Two types of homemade guava jelly, PG1 and PG3, (Ingredients used: (a) Fresh Guava: 500 g, (b) Water: 4-5 cups, (c) Two tsp of fresh lemon juice and (d) Sugar: 250 g was prepared using fresh guavas, followed by the traditional methods as shown in the above-mentioned Flow diagram (Fig. 1). Finally, the prepared jellies were put in an airtight jar and stored in a refrigerator for further analysis.

Figure 2 and 3 shows the two homemade jellies, PG1 and PG3, prepared from these two guava varieties and stored in airtight containers.

All the parameters are determined following the standard methodology as mentioned, except total carbohydrate, which was estimated according to the following equation17:

Sensory evaluation: A survey was done on market jelly vs homemade jelly in the Department of Biochemistry and Biotechnology, University of Science and Technology Chittagong, Bangladesh. Fifty participants (Teachers, Employees, and Students) aged between 20-60 years participated in the sensory evaluation, and they were unaware of which one was market jelly or homemade jelly.

|

|

Jelly was served with bread and they willingly submitted their feedback using a 5-point hedonic scale (Excellent = 5, Very Good = 4, Satisfactory = 3, Average = 3, and Poor = 1) according to taste, color, smell, flavor, level of effort, and overall taste of those jellies. Different Physico-chemical parameters of all the Jellies were determined using the standard procedures.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Morphological analysis: Table 3 shows the origin, shape, total weight, weight of non-edible waste (g), pulp weight, seed weight, and the number of seeds per fruit of the PG1, PG2, and PG3 varieties. As observed and shown in Table 3, the PG1 fruit shape was round, the PG2 fruit shape was oblong, while that of the PG3 fruit was found in oval/oblong shape. The variance in the guava fruit’s shape could result from genetics, changes in the climate, soil moisture, etc18,19.

The maximum fruit weight was observed in the PG3 variety (297.40±5.52 g). The higher fruit weight in the PG3 variety might be due to a smaller number of fruits per tree, and also depends on climatic change, sunlight, etc., which leads to an optimum number of fruits to attain good size. Again, minimum fruit weight was recorded in the PG2 (80.20±4.01 g) variety, followed by PG1 48.23±2.23 g). The location’s ecological behaviour determines whether the fruit weight is higher or lower20,21. From the data, it was observed that maximum non-edible waste was present in PG3 (2.28 g), which might be due to higher fruit weight and size with high peel thickness.

| Table 3: | Morphological analysis of guava varieties | |||

| Parameters | PG1 (Misty Guava) | PG2 (Kazi Guava) | PG3 (VNR-Bihi Guava) | p-value |

| Origin | Bandarban | Bandarban | Local market | - |

| Fruit shape | Ovoid | Oblong | Oval, Oblong | - |

| Fruit weight (g) | 48.23±2.23 | 80.20±4.01 | 297.40±5.52 | 3.14×10–17 |

| Weight, non-edible waste (g) | 0.99±0.20 | 1.07±0.23 | 2.28±0.35 | 8.44×10–9 |

| Pulp weight (g) | 38.78±2.01 | 68.30±3.98 | 273.80±5.02 | 2.97×10–18 |

| Seed weight (g) | 2.67 | 3.57 | 3 | - |

| Number of seeds per fruit | 330 | 346 | 231 | - |

| A detailed comparison of guava varieties based on physical traits like fruit size, shape, pulp weight, and seed count to identify the most productive among the three varieties | ||||

| Table 4: | Physical parameters of guava varieties | |||

| Qualitative parameters | PG1 (Misty Guava) | PG2 (Kazi Guava) | PG3 (VNR-Bihi Guava) |

| Fruit color | Yellowish-green when ripen | Dark green | Light green |

| Pulp color | Creamy white | Crispy, white | White |

| Taste | Sweet and light sour | Light sour, tasty | Medium sweet |

| Physical parameters | PG1 | PG2 | PG3 |

| Fruit length (cm) | 4.23 | 6.36 | 9.72 |

| Fruit width (cm) | 4.42 | 5.87 | 9.53 |

| Evaluation of guava types based on distinct size, weight, color, and texture differences among the three guava types | |||

Lower non-edible waste was observed in PG2 (1.07 g) followed by PG1 (0.99 g), which might be due to the lower weight and size of the Guava. The highest pulp weight was noticed in PG3 (273.80±5.02 g), and the lowest pulp weight was recorded in PG1 (38.78±2.01 g). All p-values are much less than 0.05, indicating that the differences among PG1, PG2, and PG3 for these parameters are statistically significant. The minimum seed weight was observed in PG1 (2.67 g), and the maximum was in PG2 (3.57 g). One of the criteria considered for selecting the best genotype was the combination of minimum seed weight, minimum pericarp weight, and maximum pulp weight. Additionally, the lowest seed weight may result from less photosynthetic material being transported towards the seed22,23. The maximum number of seeds per fruit was observed in PG2 (346), followed by PG1 (330) variety, while the minimum number of seeds was found in PG3 (231). The lowest number of seeds in the PG3 variety might be due to high pulp percentage. Given that the guava pulp has a diameter of 6 mm and contains 112-535 seeds, the present seed number falls within the range24.

Physical and qualitative parameters: Table 4 shows the fruit color, pulp color, taste, length, and width of different guava varieties. Fruit skin color was distinguishable for identification. Out of three varieties, the PG1 variety showed a yellowish-green skin color, PG2 showed a dark green skin color, and PG3 showed a light green skin color. Pulp color also showed variation among different Guava varieties. The PG1 variety pulp color is creamy white, while PG2 is crispy, and PG3 is white. The fruit skin color variation may result from phenotypic and genotypic expression impacted by climate18,19.

The taste of the three varieties: PG1, PG2, and PG3 was different. The PG1 tastes sweet and a little sour, PG2 tastes light sour but tasty, and PG3 tastes medium sweet or less sweet. Fruit taste is influenced by the TSS and acidity, as well by the genetic makeup of the individual genotype and climatic conditions of the locality.

The fruit length of the three varieties ranged from 4.23 to 9.72 cm. The differences in fruit length and width among PG1, PG2, and PG3 are highly statistically significant. Maximum fruit length was observed in the PG3 genotype, and minimum fruit length was observed in PG1. The maximum fruit width was observed in PG3 (9.53 cm), followed by PG2 and PG1.

Physico-chemical analysis of different varieties of guava: The pH, TSS, Titratable acidity, Moisture, Protein, Total lipid, Vitamin C, etc., contents of different guava varieties are shown in Table 5.

| Table 5: | Physico-chemical analysis of different varieties of guava | |||

| Parameter | PG1 (Misty Guava) | PG2 (Kazi Guava) | PG3 (VNR-Bihi Guava) | p-value |

| pH | 4.02±0.02 | 5.03±0.06 | 5.02±0.03 | 7.96×10–13 |

| Total soluble solids (TSS), °Brix | 9.24 | 12.16 | 12.08 | - |

| Titratable acidity (%) | 0.32±0.01 | 0.38±0.04 | 0.37±0.01 | 0.016 |

| Moisture (%) | 73.50±2.2 | 83.09±2.1 | 77.03±2.5 | 2.66×10–5 |

| Ash (%) | 0.62 | 0.32 | 0.45 | - |

| Dry-matter (%) | 31.92±2.2 | 16.91±1.1 | 23.97±2.5 | 1.70×10–6 |

| Water soluble protein (%) | 0.54±0.21 | 0.63±0.25 | 0.82±0.03 | 0.068 |

| Total lipid (%) | 0.26±0.01 | 0.87±0.02 | 0.55±0.05 | 1.29×10–10 |

| Vitamin C (mg/100 g) | 28.37±0.45 | 40.20±0.32 | 29.09±0.63 | 5.92×10–15 |

| Phenolic compounds | + | + | + | - |

| Flavonoid | + | + | + | - |

| Variations in quality attributes such as pH, total soluble solids, acidity, vitamin C, etc., content across different guava varieties | ||||

| Table 6: | Sugar contents of different varieties of guava | |||

| Parameters (%) | PG1 | PG2 | PG3 | p-value |

| Total sugar | 6.71±0.25 | 8.90±0.42 | 8.86±0.41 | 2.09×1012 |

| Reducing sugar | 4.61±0.12 | 6.85±0.22 | 6.55±0.21 | 2.16×1021 |

| Non-reducing sugar | 1.91 | 2.06 | 2.31 | 1.86×1011 |

| Compares the sugar content of various guava types, including total, reducing, and non-reducing sugars | ||||

It was observed that the extract of the guava is moderately acidic at all times. PG1 (pH 4.02) is slightly more acidic than the other two varieties. On the other hand, it was reported that the pH values of 8 different types of guava fruits were found to be varied between 3.76 to 4.47, which is very similar to current result. The highest TSS was observed in PG2 (12.16), and the lowest was observed in PG1 (9.24). TSS indicates higher sugar content in fruits and is considered one of the important criteria for dessert quality. The lowest titratable acidity was observed in PG1 (0.32±0.01%), and the highest acidity was observed in PG2 (0.38±0.04%), followed by PG3 (0.37±0.01%). So, it can be concluded that the titratable acidity of guava fruits is more or less similar.

Moisture content was found to be highest in PG2 (83.09±2.1%), followed by PG3 (77.03±2.5%), where the lowest moisture was observed in PG1 (73.50±2.2%). It was reported that the moisture contents of fresh guava samples ranged from 82.9 to 84.3%25, which is higher than our samples, PG1 and PG3. Moisture content has a major impact on the overall compositional proportion of biochemical properties and is a crucial indicator of both freshness and stability during storage. This indicates that fruit spoils more quickly at higher moisture levels and vice versa.

The protein and fat contents in different varieties ranged from 0.54 to 0.82 g and 0.26 to 0.87 g (%), respectively. The present data indicated that protein and fat are not good sources as nutrients in these experimental types. The guava varieties differ significantly in all measures but water-ssoluble protein. The biggest variations are found in the levels of total lipid, pH, and vitamin C. Very similar data on protein content were reported as follows: (2002-2004, 0.74 to 1.91%26, Edepalli 2.55%27,28 and 0.1 to 0.5%29. Further, as per the available reports, lipids are also present in minute amounts: 0.43 to 0.7 mg (%) and Edepalii N and 0.95%26-29.

Table 6 shows the total sugar, reducing sugar, and non-reducing sugar contents of different guava varieties. The PG2 variety recorded the highest total sugar (8.90%) followed by PG3 (8.86%), and the lowest amount was found in PG1 (6.51%). The highest total sugar in guava varieties PG2 and PG3 might be related to the high total soluble solids present in these varieties. It was observed that the highest reducing sugar was found in PG2 (6.85%), followed by PG3 (6.55%), where the lowest reducing sugar was observed in PG1 (4.61%). There arestatistically significant differences among the three guava varieties for all three sugar parameters. These differences in the sugar contents among the varieties might be due to the different genetic makeup and climate factors.

| Table 7: | Comparison of homemade and marketed jellies | |||

| Parameters | Market available jelly | Homemade jelly, PG1 | Homemade jelly, PG3 |

| pH | 3.1 | 3.2 | 3 |

| Color | Pink | Caramel | Pure |

| TSS (%) | 64.40±1.05 | 65.22±1.7 | 67.50±1.92 |

| Ash (%) | 0.22±0.01 | 0.45±0.02 | 0.66±0.05 |

| Vitamin C (mg/100 g) | 30.45±0.22 | 34.70±0.42 | 18.20±0.0 |

| Moisture (%) | 26.92±0.50 | 16.91±0.72 | 22.97±0.5 |

| Protein (g %) | 0.5 | 0.72 | 0.91 |

| Fat (%) | 0.04 | 0.06 | 0.07 |

| Total carbohydrate (%) | 65.30±4.05 | 70.80±5.65 | 68.52±5.02 |

| TA (%) | 0.071 | 0.091 | 0.063 |

| Phenolic Comp | + | + | + |

| Flavonoid | + | + | + |

| Nutritional differences between homemade and market guava jellies based on quantitative parameters including pH, color, TSS, ash, vitamin C, total fat, protein, and other variables | |||

A similar type of result was also reported for sugar contents in different varieties of guava30. It was also reported that the total sugar content of guava fruit pulp among different cultivars (10 nos), varied from 7.86-9.60%19, and our results are very similar to that of PG2 and PG3. Further, the total sugar contents of 8 cultivars of guava pulp were found to be varied from 4.05-6.93% for consecutive 3 years, in 2002-2004, which are very much similar to the sugar content of the recently analyzed PG1 cultivar26.

The presence of phenolic compounds and flavonoid content is also confirmed by specific tests in all three varieties of experimental guavas.

Sensory evolution and comparative study of jellies: As presented in Fig. 3, the ingredients were added and followed sequentially to prepare jellies of different cultivars, and Table 7 shows the comparative study among two homemade jellies and the market jelly. The nutritional parameters of the different types of Jelliesare summarized as; Homemade Jelly, pH: 3.0 and 3.2; TSS: 65.22% and 67.50%; Ash: 0.45 and 0.66%; Vitamin C: 34.7% mg and 18.20% mg; Moisture: 21.65 and 21,05%, Protein: 0.72 and 0.91%; Fat: 0.06 and 0.07%; Total Carbohydrate: 65.3 and 70.80% and TA: 0.091 and 0.06 for PG1 and PG3, respectively. The following reports were available for 5 types of Bangladesh Guava Jelly, TSS: 65 to 67%, Moisture: 21.53 to 22.6%, Total Sugar: 63.2 to 64.4%, pH: 2.9 to 3.2, Ash: 0.2 to 0.3% and Acidity: 0.63 to 0.73%, and the results are more or less similar to our results. The following reports were also available on the chemical characteristics of Guava Jelly31, Moisture: 68.56%, Ash: 1.09%, Protein: 0.8%, Fat: 0.6%, and Carbohydrate: 30.21%.

On the other hand, the market jellies showed the following chemical characteristics: pH 3.1, TSS (64.4%), Ascorbic Acid (30.45 mg/100 g), Moisture (26.92%), TA (0.071%), etc. The nutritional and physicochemical characteristics of ten popular jams and jelly available in local markets of Bangladesh were evaluated and some of the results are as follows32: pH: 2.5 to 3.1, Moisture: 18.5 to 21.2%, TSS: 63.80 to 67.22%, Total Carbohydrate: 78.5 to 82.0%, Fat: 0.009 to 0.23%, Protein: 0.01 to 0.09%, Ash: 0.011 to 0.09% and TA: 0.19 to 0.53%. All parameters except total carbohydrate show statistically significant differences among the three jelly types.

The TSS, acidity, pH, color, flavor, and fungal growth of guava jellies were measured at 15 days up to 60 days and 30 days up to 270 days at room temperature in glass bottles during the jellies’ storage process. After 180 days of storage, it was shown that the TSS of jelly beans did not significantly change. It started to change after 180 days. It was found that after 90 days of storage, there were no changes in the acidity of the guava jelly. It began to change after 90 days. This could be the result of sugar hydrolysis or fermentation. After 90 days of storage, there were no noticeable pH changes. After 90 days of storage, a small reduction in pH was noted in the jellies. There were no discernible flavor or color changes during the 210 days of storage. However, after 210 days, changes in flavor and color were found due to fermentation and fungus growth.

It was evident from the sensory evolution survey that the pinkish color of the market jelly drew individuals more significantly than the homemade jellies’ yellowish (pure) and caramel color. However, based on overall flavor and taste, everyone appreciated the homemade jelly’s caramel color (Fig. 3).

CONCLUSION

This study revealed distinct morphological and nutritional characteristics of local guava cultivars PG1 and PG2 grown in the highland region of Bandarban, Chattogram. The PG2 demonstrated superior nutrient content and potential for value-added product development, such as jelly. Sensory evaluation confirmed that homemade jellies offer a healthier, safer, and more natural alternative to commercial variants. The findings support the economic and environmental benefits of agroforestry-based guava cultivation in hilly areas. Future research should focus on bio-fortifying these cultivars to enhance their nutritional and commercial value.

SIGNIFICANCE STATEMENT

This study identified significant morphological, physico-chemical, and sensory differences among PG1, PG2, and PG3 guava varieties, which could be beneficial for selecting optimal cultivars for value-added product development, particularly jelly, in the hilly region of Chattogram, Bangladesh. This study will assist researchers in uncovering critical areas of guava varietal performance, processing suitability, and nutritional profiling that have remained unexplored by many. Consequently, a new theory on the varietal adaptability and commercial potential of tropical fruits in non-traditional agro-ecological zones may be developed.

REFERENCES

- Kumar, M., M. Tomar, R. Amarowicz, V. Saurabh and M.S. Nair et al., 2021. Guava (Psidium guajava L.) leaves: Nutritional composition, phytochemical profile, and health-promoting bioactivities. Foods, 10.

- Jimenez-Escrig, A., M. Rincon, R. Pulido and F. Saura-Calixto, 2001. Guava fruit (Psidium guajava L.) as a new source of antioxidant dietary fiber. J. Agric. Food Chem., 49: 5489-5493.

- Ali, D.O.M., A.R. Ahmed and E.B. Babikir, 2014. Physicochemical and nutritional value of red and white guava cultivars grown in Sudan. J. Agri-Food Appl. Sci., 2: 27-30.

- Suntornsuk, L., W. Gritsanapun, S. Nilkamhank and A. Paochom, 2002. Quantitation of vitamin C content in herbal juice using direct titration. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal., 28: 849-855.

- Abdul Hamid, Abdul Gafur, A. Nahar, G.M. Monirul Alam and S.R.M. Farid Uddin et al., 2021. Productivity and profitability of strip cropping and shifting cultivation in Bandarban, Bangladesh. J. Appl. Agric. Econ. Policy Anal., 4: 40-46.

- Borba, J., K. Fraige, D. Amorim, L. Cappelini, J. Alberice, W. Natale and E. Carrilho, 2025. Impact of nitrogen fertilization on nutrient content of 'Paluma' guavas during fruit development: A target metabolite approach. Braz. J. Anal. Chem.

- Kotsiou, K., M. Tasioula-Margari, K. Kukurová and Z. Ciesarová, 2010. Impact of oregano and virgin olive oil phenolic compounds on acrylamide content in a model system and fresh potatoes. Food Chem., 123: 1149-1155.

- Gavhane, Y.D., V.P. Kamble, R.P. Chapke, M.B. Latke and P.B. Sarvade et al., 2024. Assessment of physical characters of guava (Psidium guajava L.) cultivars under Marathwada conditions. Int. J. Adv. Biochem. Res., 8: 1012-1015.

- Leyva, A., A. Quintana, M. Sanchez, E.N. Rodriguez, J. Cremata and J.C. Sanchez, 2008. Rapid and sensitive anthrone-sulfuric acid assay in microplate format to quantify carbohydrate in biopharmaceutical products: Method development and validation. Biologicals, 36: 134-141.

- Miller, G.L., 1959. Use of dinitrosalicylic acid reagent for determination of reducing sugar. Anal. Chem., 31: 426-428.

- Ranganna, S., 1977. Manual of Analysis of Fruit and Vegetable Products. 1st Edn., Tata McGraw-Hill, New Delhi, India, Pages: 634.

- Lowry, O.H., N.J. Rosebrough, A.L. Farr and R.J. Randall, 1951. Protein measurement with the folin phenol reagent. J. Biol. Chem., 193: 265-275.

- Bligh, E.G. and W.J. Dyer, 1959. A rapid method of total lipid extraction and purification. Can. J. Biochem. Physiol., 37: 911-917.

- Blainski, A., G.C. Lopes and J.C.P. de Mello, 2013. Application and analysis of the folin ciocalteu method for the determination of the total phenolic content from Limonium brasiliense L. Molecules, 18: 6852-6865.

- Chang, C.C., M.H. Yang, H.M. Wen and J.C. Chern, 2002. Estimation of total flavonoid content in propolis by two complementary colometric methods. J. Food. Drug Anal., 10: 178-182.

- Vahid, B., 2012. Titrimetric determination of ascorbic acid contents in plant samples by 2, 6-dichlorophenolindophenol method. J. Chem. Soc. Pak., 36: 1510-1512.

- Putri, S., S.A. Marliyati, B. Setiawan and Rimbawan, 2023. Development of jelly drink bay leaf water extract with guava juice combination. Int. J. Chem. Biochem. Sci., 24: 199-205.

- Pandey, D., A.K. Pandey and S.K. Yadav, 2016. Evaluation of newly developed guava cultivars & selections under Lucknow conditions. Indian J. Hortic., 73: 334-338.

- Sharma, S. and B.L. Kumawat, 2019. Effect of leaf nutrient content at various age groups of guava (Psidium guajava L.) on fruit yield and quality in semi-arid region of Rajasthan. Indian J. Agric. Res., 53: 237-240.

- Patel, R.K., D.S. Yadav, K.D. Babu, A. Singh and R.M. Yadav, 2007. Growth, yield and quality of various guava (Psidium guajava L.) hybrids/cultivars under mid hills of Meghalaya. Acta Hortic., 735: 57-59.

- Shukla, A.K., D.K. Sarolia, L.N. Mahawer, H.L. Bairwa, R.A. Kaushik and R. Sharma, 2023. Genetic variability of guava (Psidium guajava L.) and its prospects for crop improvement. Indian J. Plant Genet. Resour., 25: 157-160.

- Singh, R.P., A.K. Singh and P.S. Dixit, 2024. Studied the growth, yield and quality attributes of guava as influenced by canopy management practices: A review. Int. J. Agric. Ext. Social Dev., 7: 25-33.

- Hussain, S.Z., B. Naseer, T. Qadri, T. Fatima and T.A. Bhat, 2021. Guava (Psidium guajava)-Morphology, Taxonomy, Composition and Health Benefits. In: Fruits Grown in Highland Regions of the Himalayas: Nutritional and Health Benefits, Hussain, S.Z., B. Naseer, T. Qadri, T. Fatima and T.A. Bhat (Eds.), Springer, Cham, Switzerland, ISBN: 978-3-030-75502-7, pp: 257-267.

- Yousaf, A.A., K.S. Abbasi, A. Ahmad, I. Hassan, A. Sohail, Abdul Qayyum and M.A. Akram, 2021. Physico-chemical and nutraceutical characterization of selected indigenous guava (Psidium guajava L.) cultivars. Food Sci. Technol., 41: 47-58.

- Adrees, M., M. Younis, U. Farooq and K. Hussain, 2020. Nutritional quality evaluation of different guava varieties. Pak. J. Agri. Sci., 47: 1-4.

- Lakshmi, E.N.V.S., S. Kumar, D.A. Sudhir, P.S. Jitendrabhai, S. Singh and S. Jangir, 2022. A review on nutritional and medicinal properties of guava (Psidium guajava L.). Ann. Phytomed., 11: 240-244.

- Rahmawati, A.N., M.W. Lestari, A.D.S. Saputri, A.A. Berliana, D.N. Fattany and O.F. Cahyaningrum, 2024. Effect of guava fruit aqueous extract on haematological profile of carbon tetrachloride induced rat. J. Biologi Tropis, 24: 434-441.

- Shariful Islam, M., R. Basri, M. Sharifur Rahman, M. Nizam Uddin, M. Shahidul Islam and S.A.A.M. Hossain, 2022. Nutritional assessment of guava for quality jelly production. Malays. J. Halal Res., 5: 24-32.

- Hossain, M.I., Z. Al Riyadh, Jannatul Ferdousi, M.A. Rahman and S.R. Saha, 2020. Crop agriculture of chittagong hill tracts: Reviewing its management, performance, vulnerability and development model. Int. J. Agric. Environ. Res., 6: 707-727.

- Sarower, K., M. Burhan Uddin and M.F. Jubayer, 2015. An approach to quality assessment and detection of adulterants in selected commercial brands of jelly in Bangladesh. Croatian J. Food Technol. Biotechnol. Nutr., 10: 50-58.

- Nielsen, S.S., 2010. Determination of Moisture Content. In: Food Analysis Laboratory Manual, Nielsen, S.S. (Ed.), Springer, United States, ISBN: 978-1-4419-1463-7, pp: 17-27.

- Imrul Mozakkin, M.J., B.K. Saha, T. Ferdous, S.M. Masum and M. Abdul Quaiyyum, 2022. Evaluation of physico-chemical and nutritional properties and microbial analysis of some local jam and jelly in Bangladesh. Dhaka Univ. J. Appl. Sci. Eng., 7: 16-21.

How to Cite this paper?

APA-7 Style

Hojaifa,

U., Akbar,

G.W., Chowdhury,

T., Chowdhury,

J.K., Absar,

N. (2025). Comparative Analysis of Physico-Chemical Properties, Morphological Traits, and Sensory Quality of Jelly from Three Guava Varieties in the Hilly Region of Chattogram, Bangladesh. Trends in Biological Sciences, 1(1), 80-91. https://doi.org/10.21124/tbs.2025.80.91

ACS Style

Hojaifa,

U.; Akbar,

G.W.; Chowdhury,

T.; Chowdhury,

J.K.; Absar,

N. Comparative Analysis of Physico-Chemical Properties, Morphological Traits, and Sensory Quality of Jelly from Three Guava Varieties in the Hilly Region of Chattogram, Bangladesh. Trends Biol. Sci 2025, 1, 80-91. https://doi.org/10.21124/tbs.2025.80.91

AMA Style

Hojaifa

U, Akbar

GW, Chowdhury

T, Chowdhury

JK, Absar

N. Comparative Analysis of Physico-Chemical Properties, Morphological Traits, and Sensory Quality of Jelly from Three Guava Varieties in the Hilly Region of Chattogram, Bangladesh. Trends in Biological Sciences. 2025; 1(1): 80-91. https://doi.org/10.21124/tbs.2025.80.91

Chicago/Turabian Style

Hojaifa, Ummay, Gazi W. Akbar, Tuhina Chowdhury, J.M. Kamirul H. Chowdhury, and Nurul Absar.

2025. "Comparative Analysis of Physico-Chemical Properties, Morphological Traits, and Sensory Quality of Jelly from Three Guava Varieties in the Hilly Region of Chattogram, Bangladesh" Trends in Biological Sciences 1, no. 1: 80-91. https://doi.org/10.21124/tbs.2025.80.91

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.